The Economic Crisis in Cuba, Its Causes, and Migration.

Without deep and coherent reforms, the outflow of human capital and the social fragmentation will continue to undermine the future viability of the national project.

During the sessions of Cuba’s National Assembly in July 2024, an official acknowledgment was made of a significant population decline, with an estimated total of around 9.7 million inhabitants—though some experts suggest the figure may be even lower. [i]

This situation reflects the largest migratory exodus recorded since the 20th century, with deep impacts on the island’s economy and social fabric.

While the official discourse continues to blame the crisis on U.S. sanctions, the current academic consensus points to internal structural causes: inertia, state control over production, and limited openness to the private sector are seen as equally decisive factors.

The lack of an up-to-date census, combined with the absence of effective public policies to reverse this migratory trend, further exacerbates the country’s demographic challenge.

Signs of the Crisis

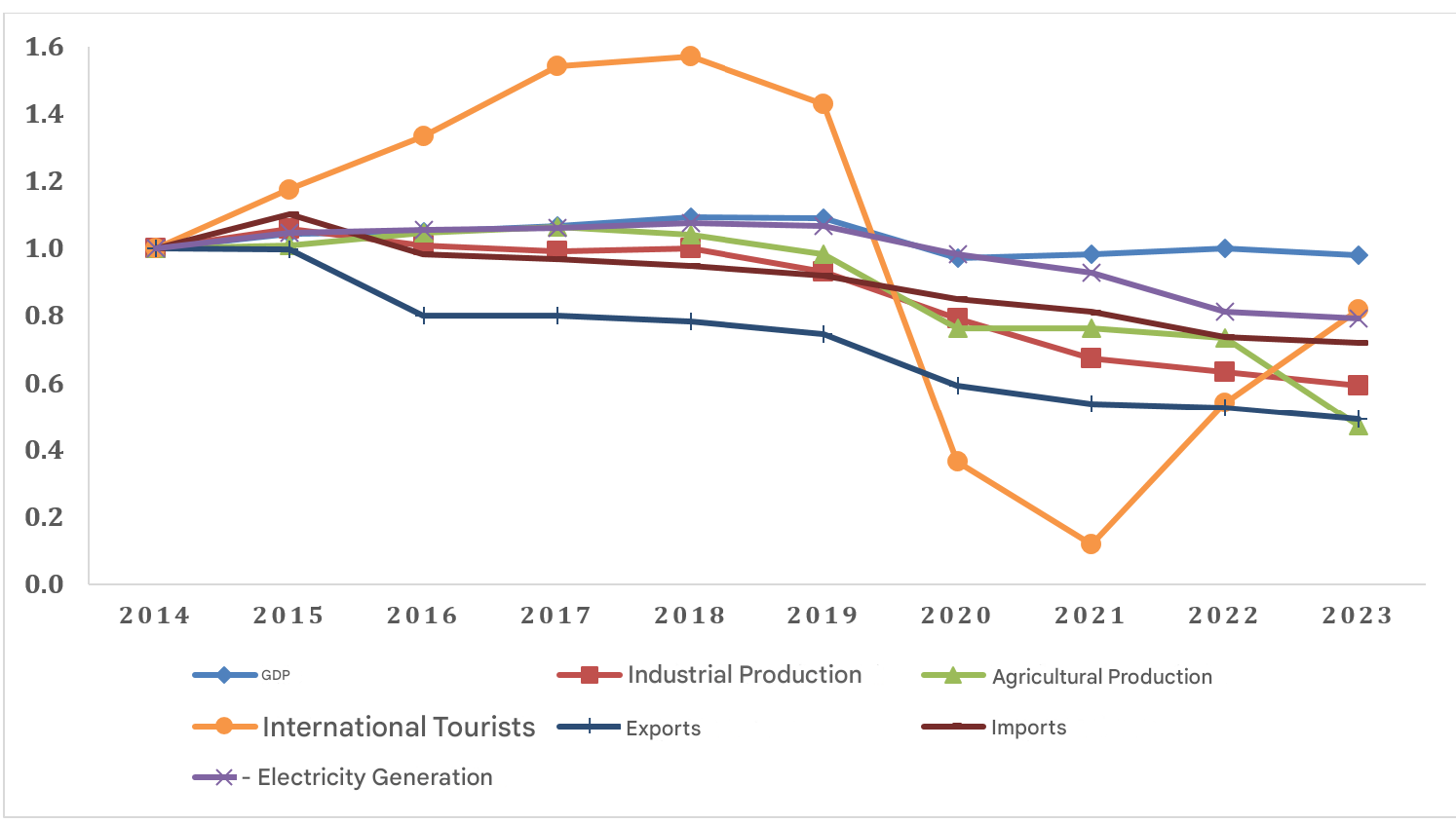

Although some indicators might suggest that the current crisis is less severe than that of the 1990s, the context is far more precarious. In 2024, GDP was more than 10% below its 2018 level[ii] , reflecting a lost decade of economic progress.

Health and education—historical pillars of the Cuban social model—have experienced accumulated deterioration, while the rationing system has partially collapsed.

Indicators such as industrial production (38.6) and the sugar sector (4.6) confirm a sharp decline. Externally, both exports and imports have fallen significantly, current account surpluses have turned into deficits, and remittances are showing a downward trend.

Figure 1 Cuba: Dynamics of selected indicators and sectors (2014–2023,2014 = 1)

Source: Prepared by the author based on various years of the Statistical Yearbooks of Cuba. National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI). Havana

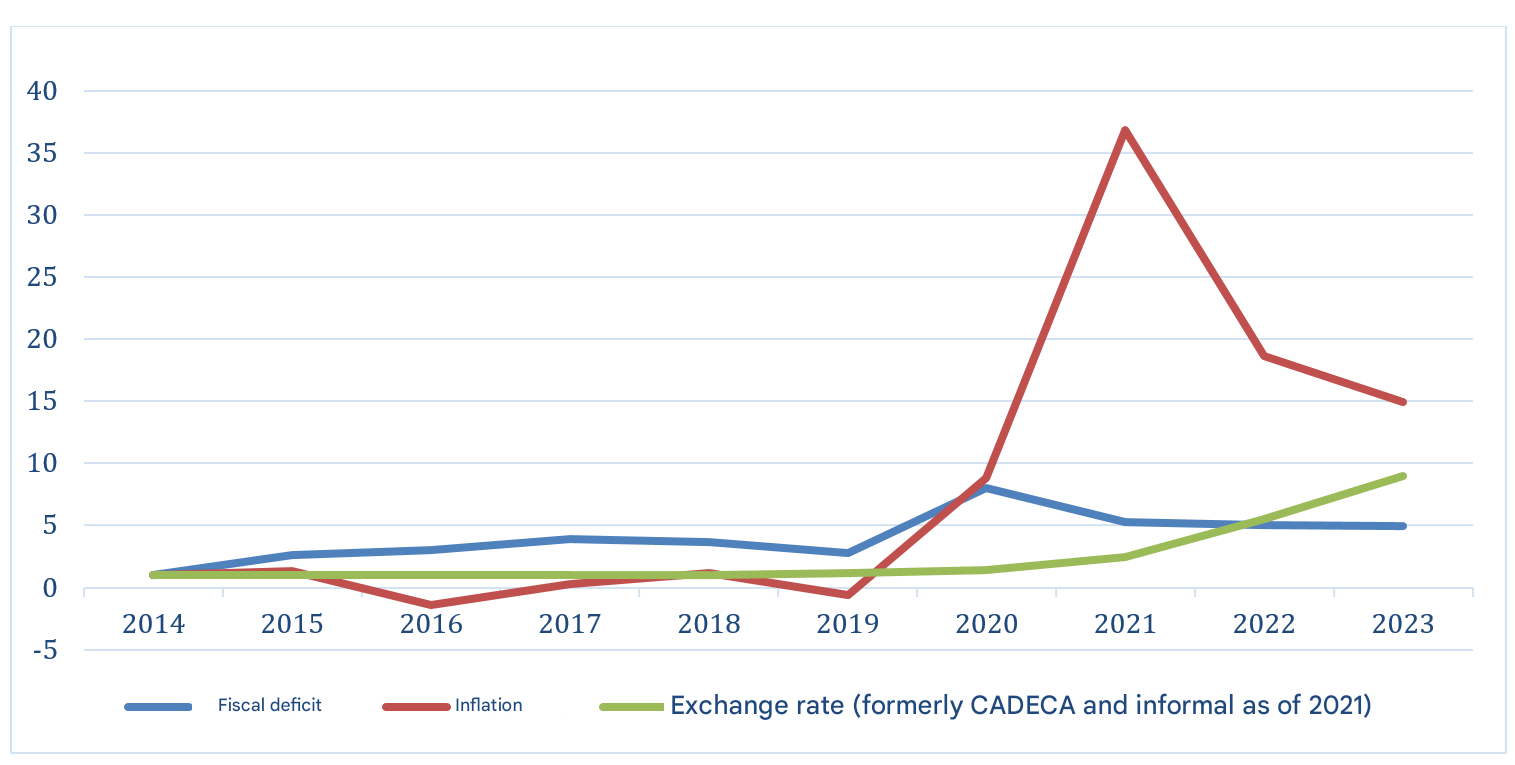

Inflation, for its part, has surged alarmingly (+77% in 2021, +39% in 2022, and +31% in 2023), [iii] while the Cuban peso has depreciated by 88%, significantly undermining the population’s purchasing power. The projected fiscal deficit for 2025 exceeds 10% of GDP, reflecting an unsustainable situation in the absence of strong external financing sources.

The combination of these factors has led to a notable deterioration in public services, a rise in informal employment, and growing social inequality. [iv]

Figure 2 Cuba: Selected Macroeconomic Indicators (2014=1)

Source: Author's own elaboration based on Cuba’s Statistical Yearbooks (various years). National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI), Havana.

Structural Failures in the Economic System

Rooted in centralized planning, the Cuban economy faces deep-seated deficiencies: underdeveloped or non-existent markets, prices misaligned with actual costs, a lack of competition among state-owned enterprises, [v] and soft budget constraints in the state business sector. Although gradual reforms have been introduced since Raúl Castro’s tenure, they have been insufficient to correct structural distortions.

The system discourages exports through state monopoly schemes and a disconnect between domestic and export prices. The absence of a transparent currency exchange market prevents producers from responding effectively to international demand.

Moreover, state-bureaucratic ownership and the lack of real efficiency incentives perpetuate unproductivity. At the organizational level, institutional fragmentation and the existence of parallel structures, such as the military business apparatus, hinder efforts toward economic rationalization. The lack of effective mechanisms for the entry and exit of firms has stifled innovation and competitiveness, negatively impacting overall productivity.

Recent Shocks

Several external events have exacerbated Cuba’s economic vulnerabilities. The Venezuelan crisis reduced oil shipments and bilateral cooperation, forcing increased Cuban spending on energy imports.

The termination of medical service contracts with Brazil, Ecuador, and Bolivia curtailed one of Cuba’s main sources of foreign exchange. In addition, the tightening of U.S. sanctions under the Trump administration affected remittances, travel, and investment flows.

The COVID-19 pandemic severely impacted international tourism, a crucial source of foreign currency. Finally, extreme events—such as hurricanes and technological accidents (the Matanzas supertanker fire, widespread power outages)—have further damaged essential infrastructure.

The cumulative impact of these shocks has been devastating, not only because of their magnitude but also because they interacted synergistically with preexisting structural weaknesses.

The recurrence of blackouts and the energy crisis have had cross-cutting effects on daily life and the country’s productive capacity, deepening the vicious cycle of economic crisis.

The Development “Model”?

After the collapse of the socialist bloc, Cuba restructured its economy around four main pillars of foreign exchange generation: international tourism, remittances, the biopharmaceutical industry, and the export of medical services. While initially successful, this model had evident structural limitations. It relied on preferential external relationships, had limited internal productive linkages, and created a high dependence on imports.

![ChatGPT. (2025, April 20). Blackout in a Cuban home: family lit by candlelight, reflecting the energy crisis [AI-generated image]. OpenAI. A family gathered during a blackout, facing each other with candles and a flashlight](/sites/horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/files/styles/cu_crop/public/content/pics/Crisi%20Econ%C3%B3mica%20e%20Migraci%C3%B3n%20Imagen%202.jpg?h=86e982f5&itok=8g6PsQsJ)

Foreign direct investment, channeled primarily into state enterprises, did not promote efficiency or competitiveness. The recent hotel expansion strategy—focused on building luxury hotels with low demand—exacerbated the inefficiency of the model. [vi] The decline in exports, remittances, and tourism has exposed the vulnerabilities of an economy that never managed to diversify or generate internal mechanisms for adjustment and sustained growth.

Moreover, the reliance of imports in domestic consumption has created a fragile economic structure, highly susceptible to any external shock that disrupts sources of foreign exchange.

Final Reflections

Cuba operates in a state of “permanent emergency mode,” characterized by economic decisions aimed at containment rather than development. The current crisis is the result of deep structural failures, compounded by successive external shocks and a conservative institutional response.

The ongoing migration exodus reflects not only economic deterioration but also profound cultural and sociopolitical changes, [vii] including access for Cubans to new nationalities, visa-free regimes, and a younger generation disconnected from the original Cuban revolutionary project.

[i] Juan Carlos Albizu-Campos, Cuba: Crisis demográfica o sistémica?

[ii] For the first time in over two decades, Cuban authorities did not provide an estimate for GDP performance in 2024, only admitting that growth was negative. Results in key export industries such as tourism and nickel, along with the deepening energy crisis, suggest the contraction exceeded the 1.9% registered in 2023.

[iii] See Vidal and Luis (2023), Cuba’s Monetary Reform and Triple-Digit Inflation.

[v] Ricardo González and Leandro Zipitría, “La conceptualización y los incentivos microeconómicos. Lo que queda por hacer,” LASA Congress, June 12–15, 2024, Bogotá.

[vi] Paolo Spadoni, The Cuban Tourism Industry: Evolution, Challenges and Prospects, LASA Congress, June 12–15, 2024, Bogotá.

[vii] See Denisse Delgado and María José Espinosa, Cuban Migration and its Social Crisis: An Overview.