Cuba in Search of a Ladder and Trigger: A Polish Perspective on Transformation

Over the past three decades, post-socialist economies have followed sharply divergent development paths, shaped less by ideology than by the institutional structuring of openness and control. This article compares Poland’s trajectory of EU-anchored integration with Cuba’s model of selective adaptation, arguing that not all forms of interdependence generate development. The comparison highlights how external ties can function either as a developmental ladder or as a structural trap.

Transformation Paths and the Problem of Interdependence

Comparative debates on post-socialist transformation usually distinguish between two broad reform paradigms. The European path, often labeled “shock therapy,” relied on rapid liberalization, privatization, and external openness to achieve a decisive break with the socialist past. Its logic was political as much as economic: only a swift rupture could restore credibility, harden budget constraints, and anchor new institutions. Poland’s early 1990s reforms became the emblematic case of this strategy.

The Asian path, associated with China and Vietnam, followed a different logic. Market mechanisms were introduced selectively under continued political control, allowing for experimentation, institutional learning, and gradual productivity growth. This model demonstrated that growth could be achieved without systemic political rupture, provided that partial liberalization was embedded in a coherent reform sequence.

Cuba followed neither trajectory. While sharing many features of late socialist economies, it avoided systemic reform and relied instead on episodic adjustments designed to preserve political control. Limited self-employment and tightly managed foreign investment created short-term relief but never translated into sustained modernization.

These divergent outcomes illustrate the power of path dependence. Poland’s initial reforms restored growth and credibility, but also locked the economy into a form of dependent integration, in which convergence relied heavily on foreign capital and multinational production networks, as described by Nölke and Vliegenthart (2009). This trajectory expanded prosperity while simultaneously constraining long-term developmental agency.

This logic echoes Gerschenkron’s classic insight on late development: backward economies cannot rely on organic market evolution alone, but must borrow institutions, capital, and organizational capacity from more advanced systems (Gerschenkron 1962). Poland pursued this strategy through European integration. Cuba’s gradualism, by contrast, reflected political continuity and structural backwardness, limiting access to external capital, technology, and institutional borrowing.

Transformation is not a single event, but a constrained process in which early institutional choices define future options. The comparison between Poland, Asia, and Cuba thus illuminates both the sources of past divergence and the narrow set of pathways through which interdependence might still be transformed into a viable development strategy.

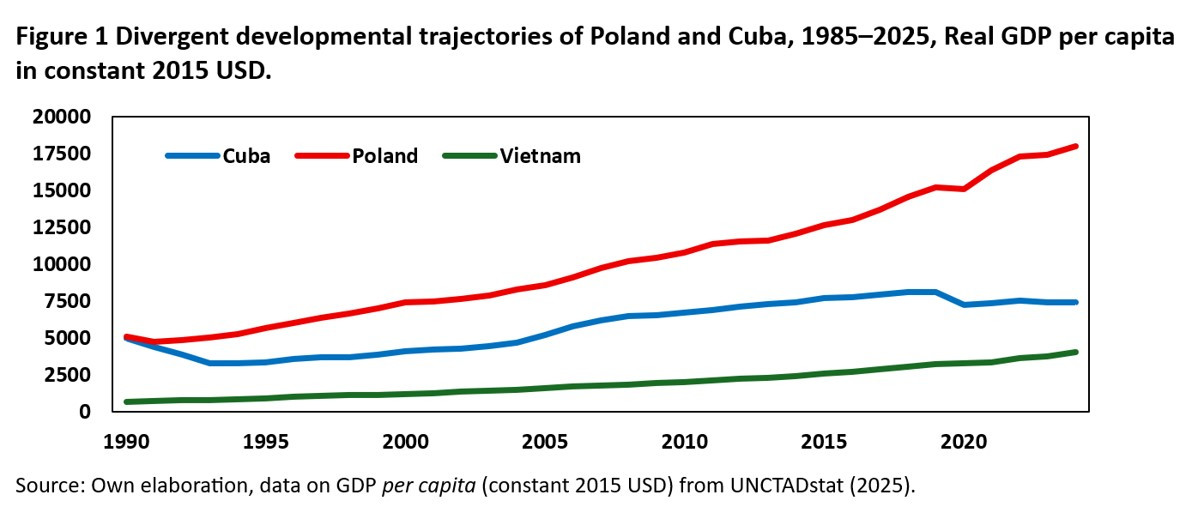

Figure 1 illustrates how similar starting conditions in the early 1990s produced sharply divergent development trajectories, highlighting how external interdependence can function either as a developmental ladder, as in Poland and Vietnam, or as a structural trap, as in Cuba.

The Origins of Divergence: Poland and Cuba in the 1980s–1990s

In the 1980s, both Poland and Cuba exhibited what Kornai (1992) described as a shortage economy: centralized planning, soft budget constraints, and low efficiency. In both cases, industrialization had lost its capacity to generate legitimacy and instead became a fiscal and technological burden. As Berend (2012) argues, the socialist model had reached a point of structural exhaustion and could no longer sustain innovation or productivity growth.

Both economies were deeply dependent on the Soviet-led CMEA for energy, markets, and credit. When external support collapsed, both systems faced a crisis of viability.

An additional factor shaping Poland’s early reform capacity was the presence of widespread bottom-up entrepreneurship that had emerged under late socialism, including informal trade, small-scale cross-border commerce, and temporary labor migration, which together constituted proto-market practices driven by necessity rather than ideology. These activities created a form of transitional capital: basic commercial skills, price awareness, and informal networks—that meant Poland did not enter the reform period as an institutional vacuum, in contrast to Cuba, where comparable bottom-up economic adaptation was systematically constrained. Crucially, the Polish regime proved capable of negotiating a peaceful political transition with the opposition, creating the institutional and political conditions for rapid economic reform, an adaptive capacity so far absent in the Cuban case.

This adaptive capacity was reinforced by the presence of parallel institutions, most notably the Catholic Church and the underground opposition, which functioned as repositories of social trust and coordination devices under authoritarian constraint, providing a credible trigger for negotiated systemic change that had no functional equivalent in Cuba.

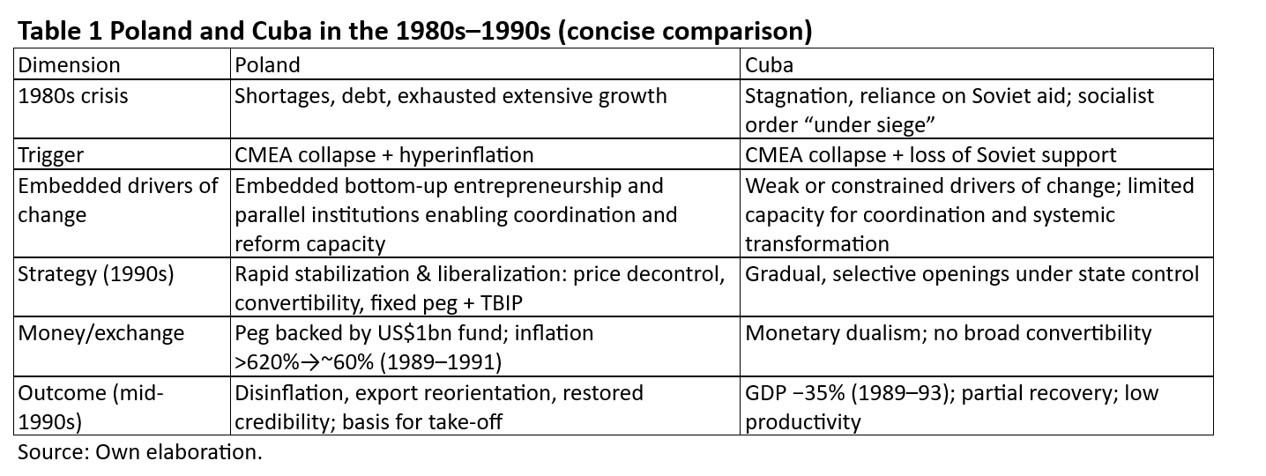

The early 1990s marked a decisive break. As summarized in Table 1, Poland opted for rapid and comprehensive reform, while Cuba pursued gradual and defensive adjustment during the Período Especial. Contemporary observers captured the Cuban strategy with a telling phrase: “capitalists, but not capitalism” (Berríos 1997). From a Gerschenkronian perspective, Poland pursued compressed development through institutional borrowing, importing rules, capital, and credibility via external integration. Cuba, by contrast, prioritized continuity and control. Selective market mechanisms were introduced, but always within a command framework. These choices, made under similar initial conditions, set the two economies on sharply divergent trajectories whose effects persist today.

Diverging Transformation Paths after 2000

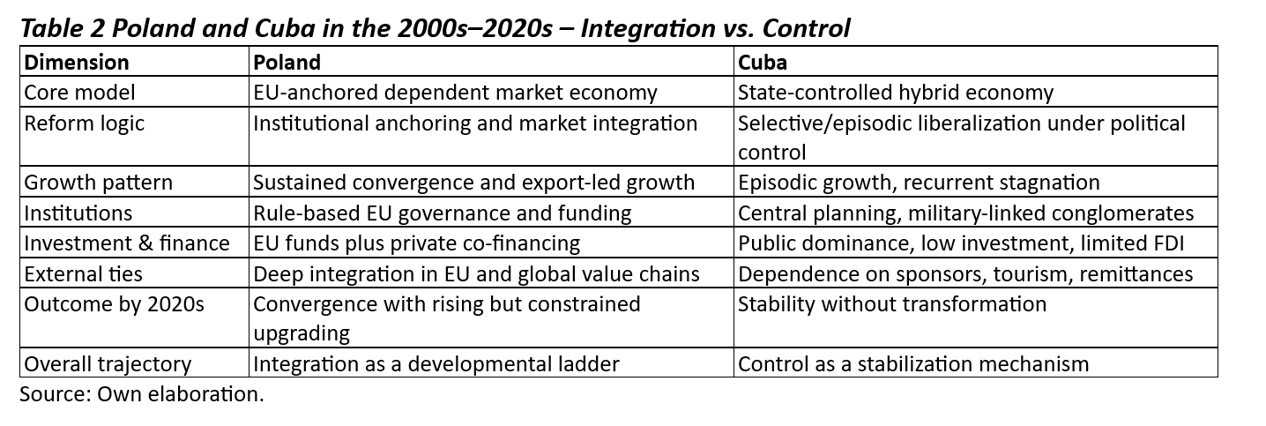

The early 2000s consolidated the divergent reform logic that had emerged after the collapse of socialism. Poland advanced through deep institutional anchoring and economic integration within the European Union, while Cuba pursued incremental reform under continued state dominance. Both achieved stability, but through fundamentally different combinations of openness and control, summarized in Table 2.

Poland: Integration through Dependence

Poland entered the twenty-first century as one of the most successful post-socialist economies. Its development model combined EU-oriented institutional convergence, market liberalization, and macroeconomic prudence. Accession to the European Union in 2004 embedded Poland in the legal and regulatory architecture of the single market, reinforcing commitments to competition and policy discipline. EU Cohesion Policy and related instruments introduced a rule-based framework for public investment built on multiannual programming and conditionality, strengthening administrative capacity and supporting large-scale modernization.

As conceptualized by Nölke and Vliegenthart (2009), Poland evolved into a Dependent Market Economy characterized by FDI-led growth and deep integration into European value chains. This model delivered sustained convergence and resilience, but at the cost of constrained domestic innovation and continued reliance on foreign capital and technology. By now, GDP per capita reached over 80 percent of the EU average, however further convergence became increasingly challenged by demographic pressure, slowing productivity growth, and the demands of the green transition.

![ChatGPT. (2026). AI-generated image: Historic square with the Polish flag and the European Union flag [Image]. OpenAI. hotograph of a historic European city square, identified by its architecture as Warsaw’s Old Town. In the center of the image stands a tall black streetlamp with two lanterns. From the same pole, two flags extend outward at an angle: on the left, the Polish national flag, with horizontal white and red stripes; on the right, the European Union flag, blue with a circle of yellow stars. Behind the streetlamp, the square opens into a wide paved plaza with people walking and gathering, some near outdoor cafés.](/sites/horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/files/styles/cu_crop/public/content/pics/Polonia%201.jpg?itok=ACAW1TEo)

Overall, Poland’s post-2000 trajectory can be described as integration through dependence: convergence achieved by embedding domestic production within European and global networks, supported by predictable, program-based EU financing, yet accompanied by persistent limits on domestic technological autonomy.

Poland’s transformation was supported not only by external institutions, but also by its diaspora, which provided capital, managerial skills, and informal credibility bridges. Remittances, return migration, and transnational business networks helped reduce uncertainty, transmit norms, and connect domestic firms to foreign markets. For Cuba, the diaspora could play a similar role, if embedded in transparent, rule-based frameworks rather than discretionary political arrangements.

Cuba: Limited Reform and Persistent Control

Cuba’s post-2000 trajectory followed a fundamentally different path. After a modest recovery supported by Venezuelan subsidies and exports of medical services, growth remained concentrated in public services, while productivity, investment, and industrial capacity stagnated. Despite repeated reform initiatives framed as “updating socialism,” the state retained control over prices, inputs, and trade, preventing the emergence of market coordination. Cuban revolutionaries rightly identified global asymmetries and the uneven distribution of gains from integration but failed to construct forms of interdependence capable of translating external ties into sustained development of the domestic economy.

The lineamientos introduced under Raúl Castro legalized self-employment, cooperatives, and later MSMEs, but always under tight political and administrative constraints. These reforms generated limited efficiency gains without producing structural transformation. Military-controlled conglomerates, weak transparency, and persistent monetary distortions continued to deter investment and suppress productivity.

![ChatGPT. (2026). AI-generated image: Havana street scene with the Cuban and Venezuelan flags [Image]. OpenAI. Photograph of a narrow historic street in Havana, Cuba, lined with tall, weathered colonial buildings featuring balconies, decorative railings, and peeling pastel façades. Two large national flags are suspended across the street between the buildings: on the left, the flag of Venezuela (yellow, blue, and red horizontal stripes with stars); on the right, the flag of Cuba (red triangle with a white star and blue-and-white vertical stripes).](/sites/horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/files/styles/cu_crop/public/content/pics/Polonia%20Cuba%202.jpg?itok=OVp_fPQ0)

The fragility of this model became evident after 2020. The collapse of Venezuelan support, tighter U.S. sanctions, the pandemic, and disorderly monetary unification triggered the deepest crisis since the 1990s. While the legalization of MSMEs created pockets of dynamism, these coexisted with inflation, inequality, and mass emigration. Cuba thus entered the 2020s with a hybrid system that modernizes selectively but remains structurally constrained by centralized control. Recent comparative analyses of Cuba and Vietnam show that sustained, market-serving reform strategies generate durable growth, while episodic liberalization under continued state control does not (Pérez Villanueva 2025) .

Comparative Synthesis

Between 2000 and 2020, Poland and Cuba stabilized their economies under external constraints but evolved in opposite directions. Poland advanced from transition to convergence by embedding openness within a rule-based European framework. Cuba preserved political continuity through selective liberalization and reliance on external rents. Poland’s dependence proved functional, rooted in institutional alignment and value-chain integration, while Cuba’s dependence remained political, anchored in state monopoly and asymmetric alliances.

By the 2020s, the divergence was complete. Poland followed a path of structured interdependence, while Cuba relied on control-based stability amid stagnation. This contrast frames the central question of the next section: how such systems adapt once their growth models reach structural limits.

Transformation Challenges in the Third Decade: Poland and Cuba after 2020

Poland Between Core and Periphery

Poland entered the 2020s as one of the European Union’s most successful convergence economies. Income per capita reached around 80 percent of the EU average, up from less than 50 percent in 2000. Yet this success now confronts clear structural limits. Productivity growth has slowed, demographic pressures have intensified, and fiscal space has narrowed under the combined shocks of the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and the energy crisis. While the economy remains resilient, the post-accession growth model (based on foreign investment, industrial specialization, and EU funding) shows diminishing returns. Low R&D intensity delayed green transition, and continued reliance on external anchors expose the constraints of dependent convergence.

These challenges unfold in a global environment increasingly shaped by what Farrell and Newman describe as weaponized interdependence: a system in which trade, finance, and technology flows are governed through strategic chokepoints rather than neutral markets. The European Union has responded by repoliticizing economic governance, embedding security and competitiveness into market rules through instruments such as industrial policy, investment screening, and carbon adjustment mechanisms. This shift strengthens European resilience but also increases asymmetries that tend to favor the industrial core, posing a strategic dilemma for countries like Poland.

Poland’s central challenge is no longer convergence itself, but how to remain fully integrated while building autonomous innovative and productive capacities. The risk is a lock-in to structured dependence: stable growth without sufficient domestic agency.

Cuba Between Reform and Stagnation

Cuba entered the 2020s amid its deepest crisis since the Período Especial. The collapse of Venezuelan support, tighter U.S. sanctions, and the pandemic led to a sharp GDP contraction in 2020 and persistent inflationary pressure. The long-delayed Tarea Ordenamiento aimed to restore macroeconomic coherence but instead eroded real wages and public confidence. The legalization of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises in 2021 opened limited space for private initiative, yet the overarching structure of state dominance remained intact.

By 2023, roughly 10,000 MSMEs were operating, revitalizing local supply chains and alleviating shortages. However, their growth is constrained by regulation, restricted access to imports and finance, and dependence on state intermediaries. The private sector functions under conditions of “managed scarcity,” combining entrepreneurial dynamism with administrative control. External conditions remain fragile: tourism recovery is slow, investment inflows are limited, and diversification efforts modest. Without credible macroeconomic stabilization and deeper institutional reform, Cuba risks remaining trapped in a cycle of partial opening and renewed constraint, stability without transformation.

Transformation at the Crossroads: Rebuilding the Developmental Ladder

By the 2020s, both Poland and Cuba had reached the limits of their respective transformation models. Poland’s structured interdependence delivered growth and institutional stability but now faces the ceiling of dependent convergence: weak innovation, demographic pressure, and limited strategic autonomy within an increasingly politicized European economy.

Cuba’s model of controlled adaptation preserved political continuity but at the cost of stagnation, low productivity, and reliance on diminishing external rents. Crucially, Cuba’s experience shows that not all forms of interdependence are developmental. The dependencies it constructed, whether on nearby or distant sponsors, provided survival and political insulation, but neither generated upgrading nor translated external dependence into domestic productive capabilities.

This constraint is reinforced by the fact that the current global environment is no longer defined by liberal globalization, but by block-based interdependence, in which access to markets, capital, and technology is increasingly conditioned by geopolitical alignment.

The contrast is structural. Poland must move from dependence to autonomy, transforming integration into innovation and strengthening domestic technological and policy capacities. In this sense, interdependence enabled rapid convergence but is now approaching its structural limits. Sustaining progress will require building a new ladder, based less on external anchoring and more on endogenous innovation, capital formation, and strategic agency. Cuba, by contrast, must move from control to renewal, turning selective liberalization into a genuine modernization drive that allows market coordination and private initiative to function. The coming decade will test both paths: whether autonomy can emerge within integration, and whether renewal can occur without systemic rupture.

Crucially, sustained developmental upgrading has historically required forms of political opening that allow rule-based openness, credible property rights, and competitive coordination to emerge.

Conclusion: Dependency, Interdependence, and the Conditions of Development

In an interdependent world, the central challenge is not how to escape dependency, but how to structure it so that it generates learning, upgrading, and long-term development. Dependency is unavoidable. What matters is whether it functions as a developmental pathway or as a mechanism of stagnation.

The comparison between Poland and Cuba shows that transformation is not a binary choice between markets and the state, but a question of how openness is governed and embedded institutionally. Poland’s integration into European markets and institutions converted external dependence into a platform for convergence, institutional learning, and productive upgrading. That pathway, however, is now reaching its structural limits, as innovation gaps, demographic pressures, and strategic constraints become more pronounced.

Cuba followed a different logic. Its external dependencies provided short-term stabilization and political insulation but never evolved into mechanisms of development. Highly centralized planning and selective, discretionary openness prevented market coordination, discouraged investment, and blocked institutional learning. As a result, interdependence reproduced dependency rather than transforming it into domestic capability.

The central lesson is structural. Systems based on highly centralized economic coordination are incompatible with development under conditions of global interdependence. Sustainable transformation requires rule-based openness, credible property rights, and competitive coordination that allow external ties to function as a developmental resource rather than a source of control. Without political change, no such framework can emerge, and any new external dependence will tend to reproduce the existing equilibrium of stability without development and resilience without upgrading.

The unresolved question is timing and trigger. Structural exhaustion rarely produces gradual change; it is usually unlocked by shocks. Whether a future regional shock, potentially originating in Venezuela, opens a window for Cuba will depend not on the shock itself, but on whether a coherent reform strategy, institutional alternatives, and credible external partnerships are already in place when that moment arrives. When transformation comes, it comes fast. The real choice is whether Cuba finds a ladder ready to climb, or only another trap waiting below.

References

Berend, Ivan T. 2012. From the Soviet Bloc to the European Union: Cambridge University Press.

Berríos, Rubén. 1997. “A Qualified Success Story: Cuba’s Economic Restructuring, 1990–1995.” Problems of Post-Communism 44 (3): 25–34. doi:10.1080/10758216.1997.11655729.

Gerschenkron, Alexander. 1962. Economic backwardness in historical perspective. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Kornai, János. 1992. The Socialist System: The Political Economy of Communism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nölke, Andreas, and Arjan Vliegenthart. 2009. “Enlarging the Varieties of Capitalism: The Emergence of Dependent Market Economies in East Central Europe.” World Politics 61 (4): 670–702. doi:10.1017/S0043887109990098.

Pérez Villanueva, Omar E. 2025. “Cuba and Vietnam: Strategies and Recent Results.” Accessed December 22, 2025.

UNCTADstat. 2025. “Gross domestic product: Total and per capita, current and constant (2015) prices, annual.” Accessed October 01, 2025.

Mariusz-Jan Radło, PhD, DSc, Professor at SGH, is an economist and Head of the Global Economic Interdependence Department at the Warsaw School of Economics. He is also the managing partner at SEENDICO, a Warsaw-based research and consulting firm. Additionally, he has extensive experience as an advisor to management boards and as a member of supervisory boards.

He has many years of research experience in areas such as regional development, global value chains, industrial policy, innovation commercialization, and international competitiveness. His recent research focuses on global strategies for strengthening companies' positions in value chains and investment opportunities. He has led research projects funded by the National Centre for Research and Development (NCBR) and the National Science Centre (NCN).

As an academic lecturer, he specializes in strategic and financial mergers and acquisitions (M&A), with a particular emphasis on their impact on company growth and competitive positioning.

He also has broad experience in the private sector, collaborating with industries such as IT, gambling, regional products, the space industry, financial services, and rail and air transport. In the public sector, he provides advisory services on regional development, industrial and innovation policy, and regional financial institutions.