Cuba and Vietnam: Strategies and Recent Results

Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva

Vietnamese leaders have demonstrated remarkably advanced strategic thinking. By contrast, Cuba’s leadership continues to defend an archaic and impoverishing model — the main factor behind its profound crisis.

Beginning in 1993, at the most difficult point of its economic crisis — the so-called “Special Period” — Cuba began a process of economic transformation that allowed it to recover somewhat from the deterioration of key macroeconomic indicators.

Behind that progress was an invisible hand: the limited introduction of elements from a market economy. Later, the government reversed parts of those new policies, and the results fell short of expectations. Between 2015 and 2019, the government implemented a counter-reform within the prevailing model of state socialism.

After the Covid-19 pandemic, which affected almost the entire planet, Cuba launched another round of economic reforms in 2021. The outcomes of those were not what had been promised — indeed, they were disastrous. The government’s key policy was to persist in promoting the socialist state enterprise, in contrast to the Vietnamese experience.

In Cuba, the government’s ideological framework tends to punish “excessive” success in the private sector. The official line remains that the “socialist state enterprise” is the main economic actor of the Cuban economy — despite its consistently failing economic performance.

By contrast, in 1986, Vietnam began its reform process, known as Doi Moi. It was founded on clear and concrete ideas: the market should serve to achieve positive economic results and thus increase the people’s welfare.

Vietnam began those initial reforms under a U.S. embargo, amid the perestroika era, and in the wake of a devastating war.

Vietnam’s economy was deeply affected by the war that ended in 1975. Power outages, the destruction of industrial facilities, shortages of labor, and logistical difficulties caused by bombings severely slowed industrial and agricultural activity. Hanoi declared at the time that its main cities, communes, power plants, hydraulic works, railroads, highways, and ports had been gravely damaged or destroyed.

The human toll was catastrophic: more than three million dead, hundreds of thousands of disabled persons, orphans, and widows, as well as an exodus of professionals and skilled workers. More than 400,000 head of cattle were lost, and thousands of square kilometers of farmland were rendered unusable.

In short, Vietnam began its reform process under conditions far more difficult than those Cuba faced in the 1990s. While both countries are governed by socialist systems led by a Communist Party, the economic outcomes are nearly the opposite.

The question, then, is why — if both started from similar socialist models, and Vietnam endured total devastation — does Vietnam now show admirable economic indicators while Cuba finds itself in a lamentable economic situation?

The answer lies in their economic models. In Cuba’s case, it continues to face a blockade by the world’s largest economy — though that is not the sole cause of its problems.

The Cuban Economy

In 2024, the state of the economy was extremely discouraging. There was no substantial improvement from 2023, and by 2025 the situation had worsened further. The same imbalances and distortions persist:

- A high fiscal deficit, though slightly reduced in 2024 compared to 2023.

- Excessive monetary issuance, as the state’s limited supply of goods and services prevents recovery of budget revenues.

- Severely constrained production, with setbacks in both agriculture and industry.

- Acute fuel shortages in 2024 and 2025.

- Limited access to foreign credit due to external debt; the current account remains negative.

- One of the smallest sugar harvests in the past century — only 40% of a reduced 2025 target was met, forcing sugar imports to cover domestic needs.

- Continuous erosion of real wages and pensions; inflation outpaces all increases.

- The once-standard basic food basket has practically disappeared.

- Export revenues fell short in key commodities such as nickel, sugar, honey, rum, and shrimp.

- Tourism has been declining since 2022, with a 25% drop in August 2025 compared to 2024 in international arrivals.

- Persistent power outages since 2024, with worsening deficits in 2025 — including four nationwide electrical collapses.

These indicators suggest that the Cuban economy is close to bankruptcy. The authorities continue to take measures that fail to reverse these negative trends.

Although several measures were announced for the second half of 2025 — such as establishing a more realistic exchange rate — it seems unlikely they will be implemented effectively.

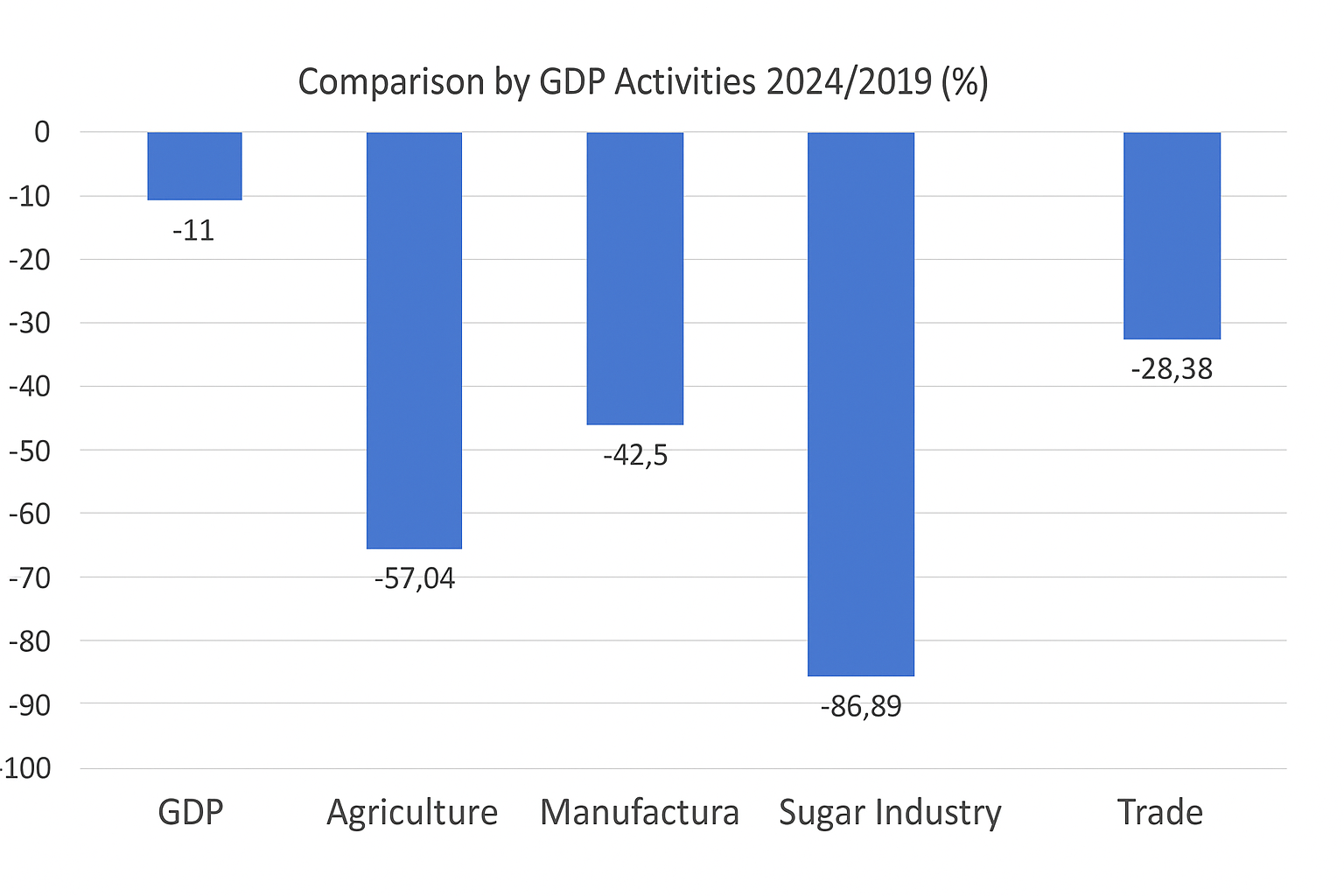

The following chart illustrates the economic landscape since 2019, including the effects of Covid-19:

Chart 1: GDP by economic activity at constant market prices (in %)

The fiscal deficit remains quite high, although in 2024 efforts were made to reduce it by cutting expenditures due to unspent investment allocations and a lack of materials for activities assigned to the budgeted sector.

Chart 2: Fiscal deficit as a percentage of GDP

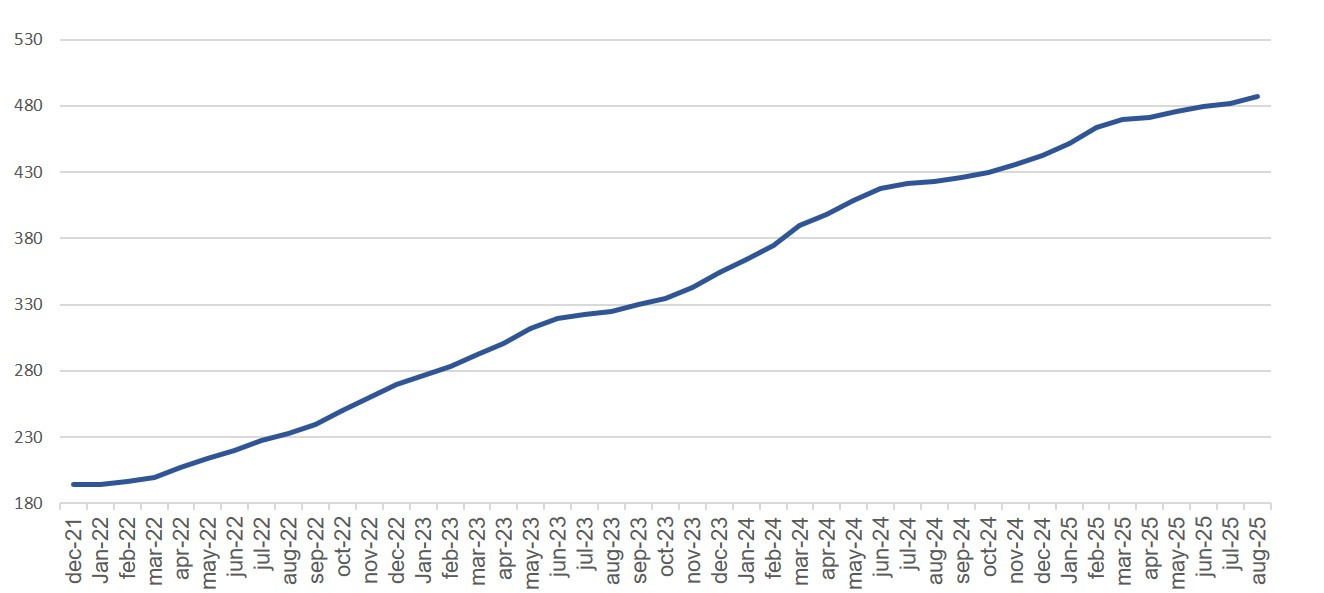

Cuba experiences runaway inflation every year, as shown in the following Consumer Price Index chart. Rising prices are affecting the population as a whole, but especially retirees, pensioners, and public-sector workers in areas such as education, health care, and public administration, among others.

Chart 3: Consumer Price Index

The Vietnamese Economy

Vietnam is undergoing an ambitious structural transformation. Since 2025, it has launched a new wave of comprehensive reforms building on the historic Doi Moi changes of 1986

At the ninth session of the National Assembly in June 2025, the government addressed a broad array of issues, including electricity, data regulation, the rights of dual nationals, and land reform.

Under Doi Moi 2.0, Vietnam has moved rapidly from announcements to tangible results, evidenced by 34 laws passed in June 2025 and extensive administrative restructuring.

The reforms rest on four pillars:

- Resolution 57 – Science and Technology

- Resolution 59 – Deeper integration into high–value-added global supply chains

- Resolution 66 – Elimination of overlapping regulations by the end of 2025 and full digitalization of a transparent legal framework by 2030

- Resolution 68 – Elevation of the private sector as “the most important driving force,” with a target of 2 million enterprises and at least 20 “national champions”[1]

Resolution 57 emphasizes technological progress, especially in prioritized sectors. The government aims to boost R&D (research and development) spending, attract foreign experts, and promote exports of high-tech products, with a goal of creating five world-class digital technology firms by 2030.[2]

Resolution 59 seeks to position Vietnamese companies higher up in global value chains, attract more capital into domestic markets, and bring in more international financial firms and professionals.

Resolution 66 mandates a comprehensive systemic review of the legal framework to eliminate overlapping or inconsistent regulations by the end of 2025, enabling both public and private sectors to achieve better results.

Resolution 68 elevates entrepreneurship as a pillar of national identity. Entrepreneurs are now regarded as “new warriors on the economic front,” explicitly tasked with driving private-sector growth. Under this resolution, the private sector is no longer a mere “component” but “the most important driving force of the economy.”

The growth strategy operates on two fronts: cultivating 20 “national champions” and expanding smaller enterprises. The government’s goal is to double the number of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) from 1 million to 2 million by 2030 and to formalize family businesses into registered SMEs integrated into the tax system.

Meanwhile, Cuba continues to embrace centralization and hyper-concentration of power. In contrast, Vietnam’s new 2.0 strategy is guided by the following principles:[3]

- The private sector comes first. Private enterprise is to become the main driver of the economy — a fundamental shift from previous approaches.

- Bureaucratic streamlining.Reduction of ministries from 18 to 13, provinces from 63 to 34, and administrative bureaucracy by 30%.

- “Transform to reform, optimize to mobilize.” Replace prior-approval systems with post-supervision mechanisms, reinvesting the savings in infrastructure, education, and technology.

- “National champions”. Develop 20 large firms integrated into global value chains while maintaining competitive pressures.

GDP growth forecasts stand at 6.9% for 2025 and 7.4% for 2026, with medium-term targets above 7% annually — compared to about 6% over the past decade.

A selection of Vietnam’s macroeconomic indicators confirms the soundness of its economic policy. Except for the pandemic year 2020, GDP has grown continuously. When early in the reform period, Vietnam faced hyperinflation, state policies soon reversed it.

Chart 4: Vietnam GDP

At the start of its reform process, Vietnam experienced hyperinflation. However, state policies soon reversed it, as shown in the following chart:

Chart 5: Consumer Price Index in Vietnam (%)

Faced with the need to integrate into the Asian region and the global economy, and to secure the resources required for its development, Vietnam promoted exports of goods and services. Today, the country exports 405 billion USD annually. When its reform process began, annual exports amounted to only 1.7 billion USD.

Chart 6: Exports of Goods and Services in Vietnam

These export levels enabled Vietnam’s trade balance in goods and services to turn positive in 2012 — a condition that continues to hold today.

Chart 7: Trade Balance of Goods and Services in Vietnam

Through their reform initiatives, Vietnamese leaders have demonstrated highly advanced strategic thinking. In contrast, Cuba’s leadership continues to uphold an archaic and impoverishing model that remains the principal cause of the island’s deep crisis. Most strikingly, monetary collections are now organized in Vietnam to send aid to Cuba.

Final Reflections

A brief review of several areas of Cuba’s economy shows that it has failed to regain previous periods of relative prosperity. The authorities still do not openly acknowledge the shortcomings of centralized planning, and the so-called macroeconomic stabilization program remains only an announcement.

Meanwhile, Vietnam’s economic indicators continue to prove that giving the market a greater role has brought success.

Cuba’s economic situation demands that the state adopt redistributive measures: stop subsidizing chronically unprofitable enterprises, increase pre–currency reform pensions, and end generalized subsidies in order to target support toward the lowest-income groups.

The oft-repeated solution remains the same: implement a comprehensive economic reform — repeatedly postponed — and grant the market the role it must play in a society burdened by economic inefficiency.

[3] Comentarios de Ricardo Torres sobre el articulo citado

![OpenAI. (2025). Symbolic photograph of the flags of Cuba and Vietnam on a negotiation table [AI-generated image]. ChatGPT (GPT-5 version). https://chat.openai.com/ On a polished wooden table, two small flags are placed side by side. On the left is the Cuban flag, with blue and white stripes and a red triangle with a white star. On the right is the Vietnamese flag, red with a large yellow star in the center. In front of each flag is a document with a pen, and further back are bottles and glasses of water. The atmosphere conveys formality and cooperation between the two countries.](/sites/horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/files/styles/cu_crop/public/content/Cuba%20Viet%20Nam_0.png?itok=2ey_f-yb)