An Approach to Poverty in Cuba

Available data reveal a worrying increase in poverty and food insecurity in Cuba. Estimates show that around 40–45% of Cubans are living in poverty.

Poverty is such a complex socioeconomic problem that in public policy it is classified as an “ill-structured problem.” [1] This means it has no clear boundaries or single definition. Its possible solutions require multiple levels of analysis and decision makers, involving actors both inside and outside the government with objectives and values that may be in conflict. [2]

Political discourse, regardless of ideological orientation, has repeatedly focused on poverty and the poor in order to manipulate its causes and consequences, ranging from the behavioral— “the poor are poor because they want to be”—to the systemic: “only a revolutionary transformation can reduce poverty.”

It is important to define and measure poverty, and to remember that those figures represent human beings with aspirations, skills, and lives that are cut short by the condition of poverty. Statistics, while essential, are instruments that cannot be detached from the moral and human complexity of some social problems.

In its most basic expression, poverty is understood as limited access to goods and services considered essential. [3] The parameters established to measure poverty make it possible to calculate the funds and resources needed to design, budget, implement, and evaluate public policies to reduce it.

All of the specialized literature, governments, and international institutions generally refer to two main types of poverty measurements: absolute and relative.

Absolute poverty measures the satisfaction of basic physical needs independently of the social context [4]. In order to measure it, a poverty threshold or line is established in the form of a minimum income required to meet essential needs in a given society. [5] For this reason, the use of the approximate cost of a basic basket of goods—which varies across countries—has become common as the benchmark for measuring absolute poverty. [6]

The World Bank, for example, uses absolute methods to measure poverty. [7] It maintains that 8% of the world’s population—nearly 700 million people—live in conditions of extreme poverty, and 44% or 3.5 billion, almost half of the global population, are considered poor. [8]

Relative poverty, in turn, assesses the satisfaction of these needs in comparison to what is assumed to be the standard of a given society. [9] Poverty can also be measured using a single variable (for example, personal income or household consumption), which is considered a unidimensional measurement. There are also multidimensional measurements that include, among others, access to services such as education, health, potable water, and electricity.

Vulnerability is a concept initially adopted in the 1970s to refer to populations affected by natural disasters. The evolution of the concept led to its expansion with a social emphasis that identified poverty and inequality as causes of vulnerability.[10] In short, vulnerability refers to future risk given present conditions. It is a term associated with a lack of opportunities and limited access to assets. [11]

Social vulnerability may encompass human groups threatened by disasters, wars, or geography, or, in particular, due to age, gender, skin color, or any other characteristic that, under certain circumstances, puts them at a socioeconomic disadvantage.

Dr. Mayra Espina explains that vulnerability includes poverty, but also other dimensions. [12] The study of social vulnerability is important because it helps provide an a priori diagnosis that could prevent poverty from growing. [13]

Cuba: Which Concept to Use, and Why

Cuban authors have used different terms to refer to low-income people in situations of economic and financial insecurity: poverty, [14] at-risk population, [15] and vulnerable population (the latter is more common in official government discourse).

Recently, in her controversial intervention at the plenary session of the National Assembly of Cuba, the former Minister of Labor and Social Security referred to Executive Committee of the Council of Ministers Agreement 10068/2025 on the “Improvement of the Policy for the Care of Homeless Persons.” [16]

It is troubling that the agreement referenced above dodges the systemic responsibility of the state and government by considering homelessness a “behavioral” problem and by calling for citizen participation in reporting homeless individuals to the authorities. This attitude, which is neither new nor exclusive to Cuba, [17] constitutes an approach to poverty that dehumanizes the poor and distances the governmental system from responsibility for a problem that has been, is, and will remain systemic.

Poverty in Cuba

The precarization of work in Cuba in recent decades has had a decisive impact on citizens’ living standards and on the growth of poverty. [18] If the cost of the basic basket is established as the absolute poverty line for Cuba, what proportion of Cubans would fall below the poverty threshold? It can be argued that Cuba offers universal health and education services, but that raises the complex issue of measuring access to quality of those goods and services.

There is, within the national territory, disparity in access to these universal services, whose generalized deterioration deserves independent consideration. Sustained inflation and monetary policies such as the banking “corralito” (limitations on access to hard currency) [19] the dollarization of the economy, and the absence of an official currency exchange market have contributed to the decline of real wages. We can assume that a collapse of real wages of this magnitude is accompanied by an increase in poverty in both absolute and relative terms.

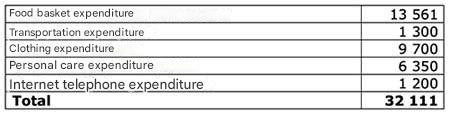

In 2023, Dr. Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva calculated the cost of the basic food basket at 13,561 Cuban Pesos (CUP) and the cost of living at about 32,000 CUP, [20] in the same year that the average salary in Cuba was 4,648 CUP. [21] Once the poverty threshold is set, poverty is estimated based on consumption surveys applied to a representative number of households.

Dr. Mayra Espina, in a recent interview on the podcast La Sobremesa produced by La Joven Cuba, explained the limitations faced by academics and non-academics seeking to study or understand poverty in Cuba due to the absence of data from the government’s consumption survey, which, even if the government continues to conduct it, does not make it public.

Despite these limitations, and taking them into account, Dr. Espina estimates, using the data calculated by Dr. Everleny, that around 40–45% of Cubans are living in poverty. [22] This figure, similar to the global proportion of people considered poor by the World Bank, reflects the deterioration in the effectiveness of Cuban public policies to maintain adequate living standards.

Table 1. Cost of the monthly basic basket for Cuba

Source: Taken from Pérez Villanueva (2023), “Calculating the Cost of Living in Cuba.”

The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) evaluates poverty beyond income, analyzing deprivations in health, education, and living conditions such as nutrition, sanitation, and housing.

Cuba ranks 19th out of 109 countries included in the report, with one of the lowest values for the period 2015–2020. The 2024 MPI report includes data collected in Cuba in 2019, which indicates that the MPI results for Cuba are not up to date and consequently must have varied in the 2020–2024 five-year period.

Cuba’s MPI of 0.003 is one of the lowest in the region, and according to this report, only 0.7% of the population was considered poor, a proportion considerably lower than the regional average of 5.8%. The report identifies Cuba’s privations as those in living standards, such as housing, sanitation, and access to electricity. In comparison with countries such as Barbados, the report considers Cuba health-related privations are relatively low, and education contributed significantly to Cuba’s MPI.

The MPI for Cuba reported an almost nonexistent level of poverty in urban areas, and although higher in rural areas, it remained low compared to regional rural averages. [23]

Today, in 2025, a nuanced analysis of the measurements covered by the MPI for Cuba is necessary. First, it is not just about having access to services, but that the access is continuous and of good quality. It is not just about being able to see a doctor, but also about the medicine available at the hospital with a minimum of guaranteed care conditions.

Drinking water, electricity, and infrastructure services are in clear deterioration in Cuba, food insecurity is increasing, while food production is decreasing, [24] and the economy is becoming dollarized in a country where the majority of the population does not receive wages in dollars.

The 2024 MPI report on Cuba needs to update the information compiled in 2019 and to provide a nuanced delving into areas such as the provision of quality goods and services in health, education, and nutrition.

Evidence of this the lack of rigorous analysis in the MPI report is the fact that Cuba was included in UNICEF’s 2024 child food poverty report. According to that report, the overall prevalence of child food poverty in Cuba is 42%, above the Latin America and Caribbean regional average of 38%.

Of the 42% of children suffering from food poverty, 9% suffer from severe food poverty. Although this is still considered a low percentage of the total childhood population, what is alarming is that the Cuban childhood poverty figure increased significantly in just one decade (2012–2022). [25]

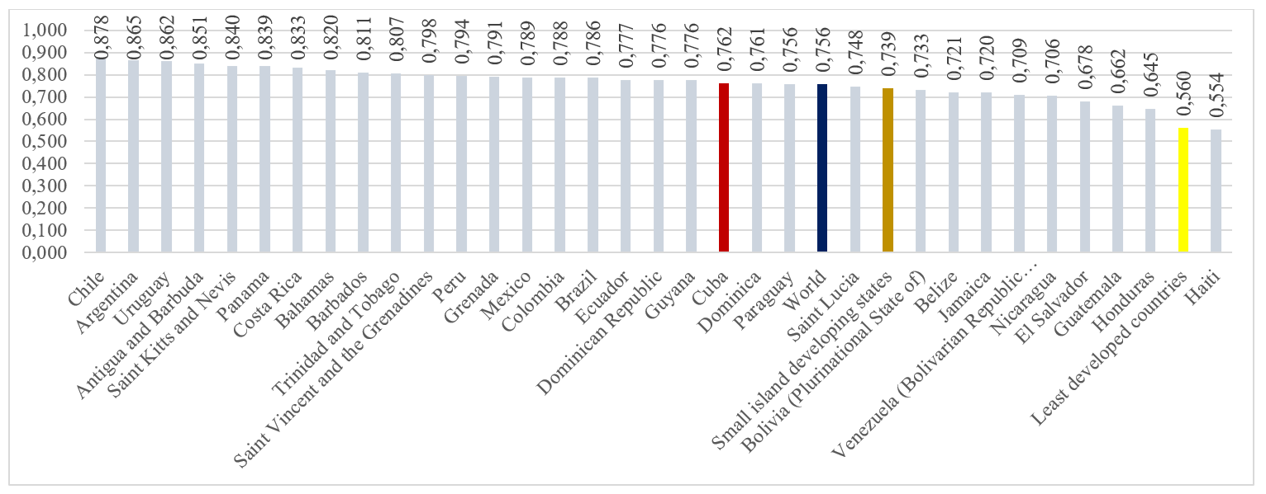

The analysis of the recent evolution of the Human Development Index (HDI) also provides a clearer picture of the deterioration of living conditions in Cuba. The HDI is a multidimensional index that helps assess the success of social policies in terms of a country’s educational level, life expectancy, and quality of life. For years, Cuba displayed one of the highest HDIs in the region. Starting in 1990, the Cuban HDI experienced decline and a slight recovery during the 2000s until 2008, when it fell and stagnated, with a slight recovery in 2022. To illustrate the fall of the Cuban HDI in perspective to others, the Dominican Republic, which historically ranked below Cuba, had the same HDI as Cuba in 2022, and by 2023 had already surpassed it. From 2021 to 2023, Cuba fell from 91st to 97th place, surpassed by multiple countries in the region. From 2015 to 2023, Cuba dropped 16 places in the HDI ranking. [26]

Chart 1. HDI in Latin American and Caribbean countries (2023)

Source: Prepared by the author using data from the United Nations Human Development Reports.

Poverty operates in partnership with inequality. The analysis of inequality in Cuba, using indicators such as the Gini [27] and Palma [28] indices, which measure inequality across defined socioeconomic strata, also provide evidence of deterioration. Unfortunately, recent inequality calculations are not available for Cuba, although we have witnessed the growing social gap resulting from thirty years of chronic systemic crisis.

The available data show that the GINI index, which was estimated at 0.25 in the 1980s, exceeded 0.4 in the 2010s without showing significant improvements during the past decade. [29]

The study of inequalities in Cuba, in addition to the indices mentioned, must also include more dimensions, such as geographic, gender, and skin color differences, educational level, access to foreign currency—whether through remittances or work—number of children, age, and many other factors that influence an individual’s ability to achieve a dignified life.

Opportunity, as an end in itself, and not as a means, has been a prevailing principle in the Cuban social policy model oriented toward egalitarianism. Guaranteeing access to education, for example, does not mean that everyone is in equal conditions to take advantage of the opportunity. Havana concentrates almost all the universities in the country, and many specialties are only offered there, which already puts its inhabitants in a situation of relative advantage compared to those of other provinces.

Opportunity, as an end in its self, ignores inequalities in the ability to take advantage of the opportunity. For example, the Economic Policy Institute conducted research that demonstrated empirically that academically successful children from poor families were less likely to graduate from university than children from wealthy families with less satisfactory academic results. [30]

This example demonstrates the need to rethink policies with more equitable approaches, focusing on opportunity as a means. This perspective begins with addressing differences in access to a dignified life that result from unequal socioeconomic conditions. It is a way to level the social and economic balance, and a mechanism of social mobility that also helps reduce poverty.

Conclusions

The Cuban case requires comparative studies of poverty and inequality in order to develop adequate social policies. The indicators to be used are not perfect. Whichever is chosen to inform the design of public policies will naturally fall short. However, establishing the real poverty threshold for Cuba is fundamental, especially in the current economic conditions, in order to understand not only the scope and dimension of the problem, but also to evaluate the resources needed to solve or mitigate it.

The addition of other dimensions, of course, contributes essential information on differentiated access to goods and services, and the segmentation of access by economic groups, age, skin color, gender, territories, among others.

The available data reveal a concerning increase in poverty and food insecurity in the country. In a context where a growing number of Cubans are exposed to risk or are in a state of extreme poverty, the official government discourse must incorporate the terms “poverty” and “inequality” into its narrative and avoid euphemisms or phrases that allude to personal behavior, instead of referring explicitly to the systemic nature of the problem.

The analysis of poverty, in order to work towards its solution, must be accompanied by a clear conceptualization, defined indicators, and transparent policies that make it possible to understand what is being referred to when speaking of “poor” people. This is a fundamental element for communication with citizens, and vital for the design and evaluation of public policies.

[1] “Ill-structured” means a complex, non-routine problem that lacks a clear, defined solution, involving ambiguous or incomplete information, multiple possible answers, and conflicting values or perspectives.

[2] William N. Dunn, Public Policy Analysis (Pearson, 2014), 74.

[3] Federico Stezano, “Approaches, Definitions, and Estimates of Poverty and Inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean,” ECLAC-UN, 2021.

[4] Stezano, “Approaches, Definitions, and Estimates of Poverty and Inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean.”

[5] Javier Ruiz-Castillo, “Absolute and Relative Poverty: The Case of Mexico (1992–2004),” El Trimestre Económico 76, no. 301 (1) (2009): 67–99.

[6] José María Larrú Ramos, “The Necessary, the Superfluous, and the Measurement of Poverty,” EMPIRIA: Journal of Methodology of Social Sciences 53 (January–April 2022): 183.

[7] The World Bank considers all those who live on less than USD 2.15 per day to be in absolute poverty, and considers poor those who live on less than USD 6.15 per day.

[8] World Bank Group, Pathways Out of the Polycrisis. Poverty, Prosperity, and Planet Report 2024 (2024), 49.

[9] Stezano, “Approaches, Definitions, and Estimates of Poverty and Inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean.”

[10] María Valdés Gázquez, “Social Vulnerability, Genealogy of the Concept,” Gazeta de Antropología 37, no. 1 (2021).

[11] Valdés Gázquez, “Social Vulnerability, Genealogy of the Concept”; Jonathan Hernández et al., “Construction and Analysis of a Social Vulnerability Index in the Young Population,” Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales 16, no. 1 (2018): 403–12.

[12] Mayra Espina, “Mayra Espina: Poverty in Cuba,” La Joven Cuba, July 23, 2025, 2990.

[13] Valdés Gázquez, “Social Vulnerability, Genealogy of the Concept.”

[14] Espina, “Mayra Espina.”

[15] Angela Ferriol Muruaga, La reforma económica en Cuba en los noventa [Economic Reform in Cuba in the 1990s], n.d.

[16] Permanent working commissions of the Cuban Parliament will examine matters of national interest, directed by Cubadebate, 2025, 00:59:30, 03:44:52.¡+´76

[17] For example, an executive order of the president of the United States, Donald Trump, signed on July 24, 2025, establishes in Section 1 a similar policy of institutionalization of homeless people.

[18] Tamarys L. Bahamonde, “The Precariousness of Work in Cuba: An Approach,” Horizonte Cubano | Cuba Capacity Building Project, August 10, 2023.

[19] Coined in Argentina during the crisis of the 2000s, corralito bancario refers to the monetary policy implemented by banks limiting cash operations to certain amounts. It may include withdrawals of funds and certain payments.

[20] Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva, “The Cost of Living in Cuba,” Horizonte Cubano | Cuba Capacity Building Project, February 11, 2023.

[22] Espina, “Mayra Espina.”

[23] Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative and United Nations Development Program, Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2024. Poverty Amid Conflict (2024).

[24] Manuel Marrero, “Prime Minister Manuel Marrero: Although Results Are Shown, Not Enough Progress Has Been Made,” December 19, 2024, 00:56:00; Omar Everleny Pérez-Villanueva, “To Put Cuban Agriculture Back on Track,” Horizonte Cubano | Cuba Capacity Building Project, February 26, 2025.

[25] Harriet Torlesse et al., Child Food Poverty. Nutrition Deprivation in Early Childhood (UNICEF, 2024).

[26] All data are taken from: United Nations Development Programme.

[27] The Gini Index is a statistical measure that quantifies inequality in the distribution of income, wealth, or other resources within a population, with values between 0 (perfect equality) and 1 (total inequality). It is calculated from the Lorenz curve, a graph where the horizontal axis shows the cumulative percentage of the population (ordered from lowest to highest income) and the vertical axis the cumulative percentage of the resource; the further the curve moves away from the diagonal line of perfect equality, the greater the inequality reflected in the index.

[28] The Palma Index is a measure of inequality that compares the total income of the richest 10% with that of the poorest 40% of the population, calculated as the ratio between the two. It focuses on the extremes of the distribution, assuming that the income share of the middle class tends to be stable; therefore, a high value reflects a large concentration of wealth in the richest sector.

[29] Mayra Espina Prieto, “Economic Reform and Social Policy for Equity in Cuba,” in Cuba: The Sociocultural Correlates of Economic Change, ed. Mayra Espina Prieto and Dayma Echevarría León (Ciencias Sociales & Ruth Casa Editorial, 2015), 208; José Luis Rodríguez, “Guidelines for Economic and Social Policy and Their Evolution 2011–2016,” Opinión, Cubadebate, April 14, 2016.

[30] Joseph E. Stiglitz, The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future, 1st ed. (W.W. Norton & Company, 2013), 24.