The Mariel Special Development Zone on its Eleventh Anniversary: Results and Lessons

Ultimately, the Mariel experience shows that the success of a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) depends not only on physical infrastructure or tax incentives, but on a coherent, stable, and competitive national economic framework.

What Are Special Economic Zones (SEZs)?

Special Economic Zones (SEZs) are geographically defined areas that operate under a different legal and regulatory regime than the rest of the country, particularly as to custom duties. These zones support industrial, commercial, agricultural, technological, and service activities by providing incentives to investors, such as tax breaks, preferential access to key infrastructure (telecommunications, ports, roads), and streamlined administrative procedures.

The primary goals of SEZs include attracting foreign investment, creating employment, diversifying the economy, increasing exports, and developing productive capabilities. Ideally, SEZs are integrated with the domestic economy through supply chain linkages, rather than functioning as isolated enclaves.

Types of SEZs include free trade zones, export processing zones, technology parks, and industrial parks. According to UNCTAD’s 2022 World Investment Report, there are more than 6,000 SEZs in 150 countries. Since their inception in the 1960s, SEZs have served as key tools for attracting foreign capital, though their real-world outcomes often fall short of political expectations.

Free Trade Zones in Cuba

Cuba’s free trade zones emerged during the economic crisis of the early 1990s, following the approval of Foreign Investment Law 77 in 1995, later complemented by Decree-Law 165. This legal framework enabled the launch of Cuba’s first three zones in 1997: Mariel, Berroa, and Wajay. Their initial objectives were to generate employment, introduce advanced technologies, stimulate exports, and attract foreign investment.

However, these zones encountered major issues:

- Weak oversight and poor management, including loose criteria for selecting operators and violations of accounting standards.

- Operational distortions, as commercial operators strayed from the intended productive focus of the zones.

- Limited economic impact, with few supply chain linkages or value-added production.

Due to these shortcomings, the government in 2003 discontinued the free trade zone policy.

The Mariel Special Development Zone (ZEDM)

In 2013, under Raúl Castro's leadership and as part of Cuba’s "updating" reforms, the Mariel Special Development Zone (ZEDM) was created through Decree-Law 313. Located west of Havana and covering 465.4 km², ZEDM aimed to overcome the limitations of the earlier free trade zones and adapt to the country’s new economic realities.

ZEDM’s stated goals include:

- Contributing to national development

- Promoting exports, import substitution, and foreign investment

- Transferring advanced technology and creating jobs

- Establishing an efficient, environmentally sustainable logistics system

However, the wide breadth of these goals have made it difficult to measure real progress.

Investments and Logistics in ZEDM

From 2011 to 2014, the first phase of the Mariel Container Terminal (TCM) was completed, one of the Caribbean region’s most modern ports, with an initial capacity of 800,000 Twenty Foot Equivalent Units (TEUs), which were expandable up to 3 million[i]. Construction was led by Brazilian firm Odebrecht, financed partly by a loan from Brazil’s BNDES bank. In 2023, dredging of the port channel was finished to accommodate Neo-Panamax ships.

Though designed as a regional logistics hub, TCM has faced serious obstacles:

- Low capacity utilization: The terminal operates at just over 40% capacity, raising questions about the investment’s value amid economic stagnation.

- Regional competition: Ports in the Dominican Republic and Jamaica now handle over 2 million TEUs each, outpacing Mariel significantly.

- U.S. sanctions: These continue to restrict trade connectivity and investor interest.

ZEDM boasts modern infrastructure beyond the port: railways, waste management systems, fiber-optic internet, electrical substations, and a business center. The Cuban state invested about $300 million per year during the zone’s first seven years.

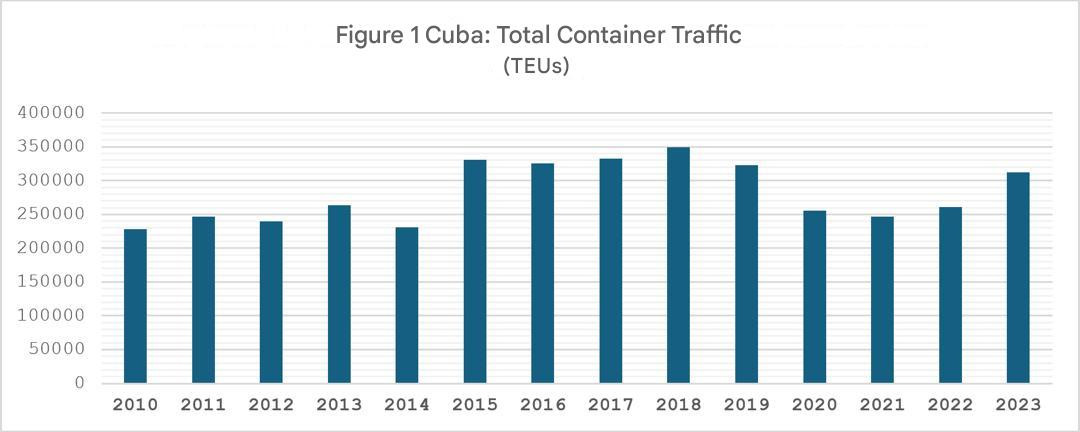

Despite its world-class design, TCM’s underutilization, dependence on foreign technology, and sanctions constraints limit its global competitiveness. Data shows that Cuba’s container traffic has remained mostly flat over the past 14 years. Even if larger ships yield cost savings per unit, the high investment appears unjustified given the stagnant economy.

Planners argue that large infrastructure projects must "anticipate" future demand, but leaving 60% of capacity unused seems beyond any reasonable forecast. The zone also failed to capture a significant share of transshipment business, which countries like the Dominican Republic and Jamaica dominate thanks to superior infrastructure, better regulatory environments, and greater trade connectivity.

However, the terminal has faced significant challenges (Haiping, 2023)[ii], such as a lack of integration with other national infrastructures, dependence on foreign technologies, and restrictions imposed by United States sanctions, which limit its ability to attract international trade at the expected scale. Available data indicates that the capacity utilization rate has barely exceeded 40%.

As shown in Figure 1, container traffic has not experienced significant variations over the past fourteen years, partly because trade is closely tied to the economic cycle. Despite potential efficiency gains associated with the ability to handle larger vessels—which lowers per-unit costs—the investment in this project appears unjustified given the needs of a stagnant economy.

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

Some argue that in large infrastructure projects, it is almost impossible to achieve optimal scale at all times, which is why it is often recommended to "anticipate" projected demand. However, leaving 60% of an investment unexploited suggests that the projected demand far exceeded reasonable forecasts.

There is also no evidence that the goals of attracting transshipment trade have been attained. For example, the Dominican Republic and Jamaica have made significant investments in the modernization and expansion of their ports, allowing them to handle much larger cargo volumes—on the order of two million TEUs.[iii]

These figures reflect not only the structural limitations of Cuban ports but also the intense regional competition, where other countries have managed to establish themselves as key logistics hubs thanks to better infrastructure conditions, more attractive regulatory frameworks, and greater connectivity with major international trade routes.

ZEDM’s Performance After Eleven Years

By the end of 2023, ZEDM reported[iv]:

- 64 approved projects, with $3.2 billion in committed capital

- Just over $1 billion in executed investments

- Nearly 10,000 direct jobs created

Foreign Capital

Of the 64 approved projects, 12 are Cuban-owned. This suggests that only 52 projects involve foreign investment. However, many of those foreign investors already operated in Cuba. In 2019, 49% of foreign companies in ZEDM were subsidiaries of existing businesses in Cuba. If that proportion holds, only about 27 truly new foreign firms entered the zone over a decade — fewer than three per year on average.

Additional concerns include:

- Only one-third of committed capital funds have been disbursed.

- Excluding Cuban firms, foreign investment averages just $270 million per year, an insufficient return compared to the $300 million in related public infrastructure spending annually.

Job creation results are relatively positive, with nearly 10 direct jobs per $1 million invested — better than the regional average. Still, there’s limited data on exports, import substitution, or domestic supply chain integration.

Lessons from the ZEDM Experience

- Limits of Tax Incentives Alone. Foreign investment decisions depend on many factors, including market size, resource availability, and macroeconomic stability. Cuba has focused too heavily on fiscal incentives while neglecting critical issues such as:

- Confidence in economic policy

- Reliable access to information

- Bureaucratic efficiency and legal stability

- Labor hiring practices

Macroeconomic management

Without broader structural economic reforms, foreign capital cannot offset Cuba’s systemic economic weaknesses.

- Lack of Integration with the Domestic Economy. ZEDM’s economic spillovers have been minimal. Its disconnect from a strong domestic private sector — a natural counterpart to foreign investors — is a serious bottleneck. Relying on inefficient state enterprises reduces the economy’s capacity to absorb technology and capital. Promoting a dynamic private sector is essential.

Risks of Using Public Funds. Cuba has poured significant public funds into ZEDM amid chronic foreign currency shortages. These large-scale projects carry high risks, especially in an unfavorable macroeconomic environment. Moreover, tax exemptions for investors represent lost revenue that appears unjustified by the limited benefits the country has received from the investment.

This is particularly troubling given that tax breaks for domestic private capital investment have been completely eliminated. If fiscal deficit reduction is a core priority, then incentives should be more evenly distributed. There’s also a risk that domestic businesses relocate to ZEDM simply to benefit from tax advantages, weakening the broader economy.

Ongoing Challenges

- Complex Regulations and Bureaucratic Delays. Slow approval processes discourage investors. Despite public recognition of this problem, the situation has not improved and may have worsened. Policy inconsistency further undermines investor confidence.

- Weak National Industry. The lack of local suppliers hinders supply chain integration. Cuba’s productive structure has long suffered from poor internal linkages. In 2023, the industrial production index (1989=100) fell to 38.6 — the lowest in 20 years. This reflects both capacity shortages and the rigid vertical administration of the economy, which restricts horizontal relationships across ownership types.

- Impact of U.S. Sanctions. Financial operations and international trade remain heavily constrained. But many current sanctions were already in place when the project was conceived, including Cuba’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism. Several European banks had already been fined for violations. A realistic project plan should account for such conditions and manage expectations accordingly.

Conclusion

The ZEDM represents Cuba’s effort to modernize its economy and integrate into global value chains. While it has created modern infrastructure and attracted some investment, its overall economic impact remains limited due to structural problems and weak supply chain connections.

To achieve its initial goals, the zone must be supported by broader national economic reforms, including:

- Strengthening the domestic private sector

- Simplifying regulations and cutting red tape

- Making tax incentives part of a holistic economic development strategy

In the end, Mariel’s experience shows that building infrastructure and offering tax breaks are not enough. Success depends on a stable, coherent, and competitive economic environment in the country for the foreign investor.

As the empirical evidence shows, even projects with exceptional growth may slow to match the average pace of the national economy over time. Simply put, the fate of the zone is tied to the fate of the broader Cuban economy.

As one economist put it: “There are no shortcuts to development. You have to do the work.”

[i] https://www.tcmariel.cu/infraestructura/

[ii] Haiping, L. (2023). En Y. Tao, & Y. Yuan, Annual Report on the Development of China’s Special Economic Zones (2020). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

[iii] https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/dataviewer/US.ContPortThroughput. The acronym TEU (short for Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit) represents an approximate unit of measurement used in maritime transport, specifically for container ships and port terminals, and is expressed in containers. One TEU corresponds to the cargo capacity of a standardized 20-foot (6.1-meter) container—a metal box of standard size that can be easily transferred between different modes of transport such as ships, trains, and trucks.

[iv] https://www.zedmariel.com/ y http://www.cubadebate.cu/noticias/2024/06/12/zona-especial-de- desarrollo-mariel-proyecta-crecimiento-a-pesar-de-complejo-escenario-economico-video/