Precarious Work in Cuba: An Introduction

Labor precarity and precarious work are also manifestations of the Cuban economy’s structural crisis. It will not be resolved in the short term, as its causes are multiple and its scope extends to almost all sectors of the national economy.

The thirty years of Cuban private sector expansion since 1993 have changed the work landscape for both employers and Cuban employees. The government went from being the country’s almost-exclusive employer to sharing the labor market with different actors, which include, in 2023, not only self-employed individuals (trabajadores por cuenta propia, “TCPs”) but also other private businesses (national and foreign), cooperatives and local development projects organized as private-public partnerships.

In this scenario, it is difficult for a Cuban to find a non-precarious job. As a rule of thumb, in the public and private sectors, waged employees have little control over working conditions and salaries, albeit for different reasons. Low salaries in the public sector, with limited to no access to foreign currency, encourage workers to move to the private sector, which can pay higher salaries and provide access to hard currency to its employees.

At the same time, workers in the private sector are subjected to dismissals without cause or severance pay, long working hours, exceeding those provided by the labor code for the government sector, only discretionary time off; and they lack other rights provided by the state-controlled sector, such as paid maternity leave. Currently, there are no concrete mechanisms for employees to force private employers to comply with the labor code; nor are trade unions playing a role pushing for better labor conditions or negotiating on behalf of employees with employers. Hence, in the Cuban private sector, workers lack some employment protection.

For the purposes of this article, we limit the discussion to waged employees, that is, individuals who go to the labor market to “sell” their skills to perform certain tasks for employers. Employers are entities or individuals who “buy” these skills and pay for them with salaries—money—and/or other benefits. To simplify the analysis, we shall focus on the workers in the public sector, and workers in the private sector, either domestic private MIPYMES (micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises by their acronym in Spanish) or joint ventures with foreign investors.[1]

What is “Precarious Work”?

There is not a unique definition for precarious work, and the concept has evolved (Campbell & Price, 2016) with the development achieved by societies and capitalism. However, when referring to precarious work, authors mean the concrete employment/working conditions that combine multiple levels of lack of security and protection, inside and outside of the work environment, impacting social groups particularly susceptible to onerous working or employment conditions (Campbell & Price, 2016; Feng, 2021; Standing, 2011).

Precarious workers, then, are those subjected to insecure working conditions, which extend to and affect their overall well-being within society (Campbell & Price, 2016). In this article, we will only consider certain aspects of labor precarity for Cuban workers.

We should note two important characteristics of employment in Cuba. First, even though the boundaries are clearly defined by law in the new MIPYMES, government statistics do not separate those working in the national private sector into owners and employees, which is an essential distinction when analyzing precarious work. The lack of this distinction in the government compiled data masks other inequalities in employment. Women, for example, tend to participate in the private sector mostly as employees rather than as proprietors.

In 2012, the percentage of women working in the national private sector as waged workers was 67%, versus 11% of their male peers (Maqueira & Torres, 2021), placing them at a disadvantage in achieving higher income and, thus, goods and services. Also, it is not the same to work for an employer than being the employer.

Second, Cuban labor law still needs to be modified for a context wherein the government is not the almost-exclusive employer. Within current conditions, rights such as the right to strike should be codified to guarantee workers a greater capacity to negotiate with their employers.

Precarious Work and Precarious Workers in Cuba

It is impossible to address in a single article the several manifestations of each of these phenomena per sector and segments of the labor market. However, we can identify some general aspects of what makes work precarious in Cuba and, therefore, increasing labor precarity for Cubans.

Real Wages and Households Consumption

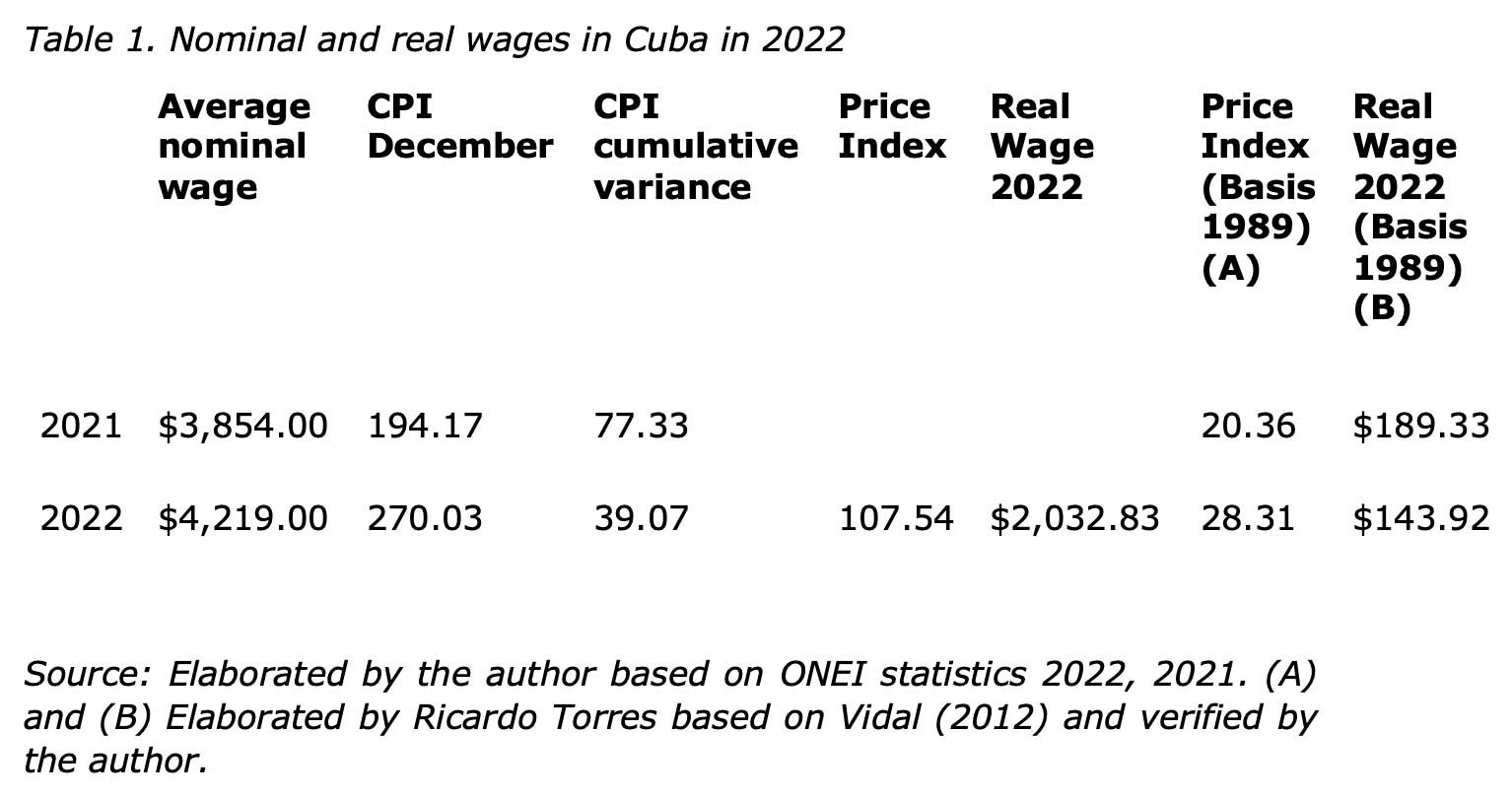

Using data from the CPI (Consumer Price Index) and average nominal wages issued by the ONEI (Cuba’s Office of Statistics and Information) for the years 2021 and 2022, we can calculate the changes in Cuban salaried employees’ real wages from December 2021 to December 2022. Cuban citizen’s real wages for 2022 were CUP 2,032 (Cuban pesos), far below the nominal wage of CUP 4,219. If we take the year 1989 as the base, Cuban citizens’ real wage in 2022 was only CUP 185. It is worth noting that the available data, although useful, are still limited by the methodology used in the calculations, which excludes important segments of the market in which Cuban citizens access consumer goods.

Economist Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva estimated that, on average, a Cuban citizen would need a salary upwards of CUP 32,000 per month to access essential goods (Pérez-Villanueva, 2023). To the low average nominal wage in Cuba we should add factors that impact the quality of life and work, such as the devaluation of the Cuban peso vis a vis foreign currency, the lack of consumer goods, and the limited access to markets.

The commuting distance to work and markets, the need to check numerous markets in person, and the hours spent waiting in lines to procure essential goods at stores, are all distinctive elements defining labor precarity in Cuba. To provide a more complete picture of the general living conditions faced by Cuban households we must add the persistent problems with the poor supply of drinking water and power (blackouts).

The productivity-wages-inflation vicious cycle still has a notable influence in decision-making in Cuba. Low productivity levels in the state-owned productive sector led it to adopting the narrative that only an increase in productivity with a positive impact on production could result in better salaries without increasing inflation. In the context of Cuba, aggregate productivity calculations are based on national averages and are controlled through bureaucratic mechanisms which perpetuate the cycle of low productivity and low salaries (Vidal, 2015).

Nevertheless, contextualized empirical studies, such as the one published by economist David Card, have proven that not every increase in minimum wage causes a fall in employment levels—which directly questions the logic behind the increase in the level of prices-inflation (in the government sector)—if the level of wages is increased.

Moreover, in the Cuban case, price mechanisms are still centralized, and their poor design is not based on salaries´levels. In any case, the current inflationary spiral in Cuba has absorbed the slight increase in salaries and pensions, and the cause is not the almost marginal increase of the latter, but the distorted monetary policy known as “Tarea Ordenamiento” (TO), which impacted the productive sector.

There is no doubt that in the current Cuban economic conditions, the average wage of the public sector is not enough to guarantee the purchase of basic goods and services for an individual, much less a family. Wages in the non-public sector, albeit higher, come with other elements of labor precarity: working hours exceeding 40 weekly hours, discretionary unpaid time off, lack of protection for vulnerable workers—single mothers, chronically ill people—and the often-overlooked elements of discrimination, based on gender and race, which, since subtle, are hard to combat.

Accessibility

In urban planning, accessibility refers to the distances one must travel in urban centers to access not only the workplace, but also markets and recreation centers, for example. It is about the geographical space’s potential for social interactions (Järv et al., 2018). A vital element is the time we take to move from our homes to the workplace and recreation centers. Empirical studies have proved the correlation between significant increases in stress levels and the time we take to cover the distances that separate us from our jobs (Javadian, 2014).

Cuban waged workers do not have the means to buy cars or pay for taxis and most of them depend on a deficient public transport system. Given the poor conditions and unreliable schedules of urban public transport and the year-round high temperatures, transportation is an element that must be considered when analyzing work precarity.

In Cuban markets, product shortages result in a choice of goods that varies widely, forcing Cuban citizens to visit several markets, at considerable distances from each other, to acquire essential goods. Moreover, purchasing at any of these markets requires waiting in line. All those factors worsen the Cubans’ quality of life and contribute to precarity for Cuban workers.

Working Conditions

As a rule, conditions in workplaces in the state-controlled sector are poor, although exceptions exist. We can highlight the lack of air conditioning during periods of very high temperatures and workers performing risky jobs without proper protection equipment or working out in the open without proper protection against environmental risks.

On the one hand, the law on MIPYMEs itself limits progress for their workers, in particular because many types of professionals are generally prohibited from working in the private sector. On the other hand, foreign companies take advantage of the general work precarity and offer low salaries to Cuban workers. Moreover, Cuban workers are required, when working for foreign companies, to be hired by and paid by a government employment agency.

The state-controlled sector offers the advantage of respecting labor rights such as paid time off and maternity leave, as well as pay scales. There are also opportunities for those professionals who cannot provide their services in the national private sector to exercise their profession. On the other hand, the Cuban public sector maintains low wages with limited opportunities for increases and no capacity to negotiate working or salary-related conditions. In this sense, unionization of public workers offers limited advantages. Underemployment or hidden unemployment

Carmelo Mesa-Lago has referred multiple times to hidden unemployment, understood as the workforce underutilization as a result of full employment policies aiming to reduce visible unemployment (Mesa-Lago, 2010). Hidden unemployment, even if it works as a cushion to reduce unemployment in times of crisis, also affects work productivity, negatively impacts general wages, and increases work indiscipline by lacking incentives (Mesa-Lago, 2010).

The ECLAC (the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) calculated hidden unemployment for Cuba until 1998, when the number reached 25.1% of employed individuals, which when added to the 6.6% of visible unemployment, placed unemployment level at over 30% of the labor force (Mesa-Lago, 2010).

The Cuban labor context has changed a lot since 1998. The “update” to the economic model promoted by Raúl Castro since 2011 aimed to increase efficiency in the state and government sector in the economy and made the reduction of redundant job posts a priority.

Although the Cuban Government has reduced its role as employer, thus partially achieving that goal, it continues to be the main employer of the economy, occupying around 64% of the total number of workers in 2022 (ONEI, 2022), while 23% of employees work in the private sector. As explained above, we do not know how many of them are salaried workers and how many are business owners.

Although the public sector controls most of the production of goods and services, it still does so under an administrative and business system based on bloated staffs, with a higher number of administrative workers that are economically inefficient. For example, the reduction of administrative personnel promoted by Raúl Castro effectively reduced employment in the public sector until 2018, when it reached its lowest point at 282,100 workers. However, the following year, the number started to grow once more, increasing by 8% in 2022 in comparison to 2018 (ONEI, 2022).

We note that the increase of administrative personnel in the government sector contrasts with the reduction of total workers from 2019 to 2022 by 2%. One of the causes for this reduction is clearly the departure of over 300,000 Cubans in 2022 (Albizu-Campos & Díaz-Briquets, 2023). This emigration will, sooner rather than later, have even more significant repercussions on the Cuban labor market.

In Cuba, tourism related industries, especially business services, housing and rental activities, experienced the most significant growth in 2022 compared to 2019. This is the same period where activities worldwide first plummeted due to Covid-19 and then rebounded, but slowly in the tourist industry. However, Cuban public policy prioritized investments in slow recovering economic areas over essential sectors, such as agriculture and livestock farming. This policy contributed to Cuba’s inflation rate - one of the highest in the Latin American region - reducing real wages by 24% in 2022 compared to 2021, and increased food insecurity.

Participation

Cuban workers’ limited power to negotiate their salaries or work conditions contributes to the labor precarity. Cuban trade unions, legally tied to the government, are both judge and party in labor negotiations. In this sense, trade unions represent the interests of the government, as main employer, instead of the interests of the employees they are supposed to protect.

In the non-public sector, unions have not yet acquired influence in order to push for the enforcement of laws protecting workers and work conditions: limited work hours, paid time off, maternity leave, and protection against arbitrary dismissals. The right to strike is part of workers’ effective participation in fashioning their work environment, and a mechanism to push for necessary changes in salaries and working conditions. The absence of the right to strike is understood by literature on labor as another element of work precarity (Standing, 2011).

Conclusions

The study of the labor universe sheds some light on a country’s living conditions. The analysis of different aspects of labor precarity in Cuba shows us that its effects extend to everyday life with serious impacts on the quality of life for all. Low real wages, poor employment conditions, underutilization of the workforce’s skills and an almost inexistent capacity for workers to change such conditions, contribute to social discontent, inequalities, and emigration. All these factors will have a long-term negative effect on society and the country’s economy.

Labor precarity and precarious work are also manifestations of the Cuban economy’s structural crisis. It will not be resolved in the short term, as its causes are multiple and its scope extends to almost all sectors of the national economy.

The rising levels of precarious workers in Cuba, if not addressed, could worsen social tensions and reduce trust in the institutions responsible to find effective responses to the country’s problems. If economists believe, in general, that inflation is the thermometer of an economy’s health, we could say that the levels and characteristics of work precarity reflects a society’s health.

It is not enough to have universal healthcare and education services. Albeit essential, they need to be combined with a proper system to reward its citizens for their honest work and allow them to access a decent quality of life.

References

Albizu-Campos, J. C., & Díaz-Briquets, S. (January 26, 2023). Cuba and its Emigration: Exit as Voice | Cuba Capacity Building Project.

Bahamonde, T. L. (2018). Mercado Laboral Cubano: Distorsiones y Retos. Annual Proceedings of The Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy, 28.

Campbell, I., & Price, R. (2016). Precarious Work and Precarious Workers: Towards an Improved Conceptualisation. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 1(19).

Feng, X. (2021). The making of labour precarity: Three explanatory approaches and their relationship. Labor History, 62(5-6), 537-555.

Järv, O., Tenkanen, H., Salonen, M., Ahas, R., & Toivonen, T. (2018). Dynamic cities: Location-based accessibility modelling as a function of time. Applied Geography, 95, 101-110.

Javadian, R. (2014). The journey to work: Exploring commuter mood and stress among cyclists, drivers, and public transport users [For the Degree of Master of Science in Administration (Management)]. John Molson School of Business-Concordia University.

Maqueira, A., & Torres, A. (2021). Cuba in the time of COVID-19: Untangling gendered consequences. Agenda, 35(4), 117-128.

Mesa-Lago, C. (2010). El desempleo en Cuba: De oculto a visible. Espacio Laical, 4, 59-66.

Pérez-Villanueva, O. E. (February 11, 2023). Calculating the Cost of Living in Cuba | Cuba Capacity Building Project.

Standing, G. (2011). The Precariat. The New Dangerous Class. Bloomsbury Academic.

Vidal, P. (2012). Capítulo 6. Desafíos monetarios y financieros. In P. Vidal & O. E. Perez (Eds.), Miradas a la Economía cubana: El proceso de actualización (pp. 97-112). Editorial Caminos.

Vidal, P. (January 10, 2015). La reforma y el salario real. Cuba Posible.

[1] The manifestations of precarious work differ between the Cuban and overseas private sectors. Due to the short length of this article, we cannot address the different aspects of those key differences and will have to address them methodologically as “private sector.”