Overregulation and Administrative Burden in Cuban Public Administration

Overregulation and administrative burdens significantly erode the relationship between citizens, the state, and the government. They undermine trust in institutions and increase perceptions of country risk.

Regulations and the government bureaucracy—referred to in this article as “public servants”—are essential components of public administration. In Cuba, public administration spans all levels and sectors of government, where bureaucrats perform both routine and non-routine tasks that support the functioning and sustainability of the state and government.

The role of public administration and its bureaucracy is, fundamentally, to mediate, design, and implement public policies. These policies shape the scope of government influence, structure relationships between the state and its citizens, and govern interactions among institutions—public, private, and otherwise.

Within the bureaucratic hierarchy, tasks are divided: higher-level officials tend to design public policy, while mid- and lower-level bureaucrats are responsible for its implementation.[1]

In Cuba, those performing these bureaucratic roles often intrude on each other’s mandate and create disruption. As a result, public administration acts more as a mechanism of control than facilitation, shaped by the centralized nature of the bureaucratic socialist state.

Moynihan et al. (2015) define “administrative burden” as the degree to which individuals experience the implementation of public policy as costly or difficult.[2]

Cubans have informally developed their own term for this phenomenon: the “internal blockade.”[3] Scholars have noted a link between high levels of administrative burden and tendencies toward inaction, limited creativity, and poor policy outcomes among public officials.[4]

Administrative Burden in Cuba’s Overregulated Environment

The bureaucratization of the Cuban state has resulted in a sprawling administrative apparatus that includes central government ministries, local governments, state enterprises, budgeted units, enterprises, and nonprofits—all strategically subordinated to the central government.

This structure impairs the efficiency and effectiveness of public policy design and implementation.[5] Cuba suffers from excessive administrative regulation that hampers economic performance across both the state and private sectors.[6]

Cuban legislation is often designed more to control than to regulate economic, political, and social activities. This control is exercised through the extensive—and sometimes unchecked—authority of bureaucratic bodies at all levels of government. These agencies often have overlapping responsibilities or lack clearly defined roles, resulting in administrative confusion, inconsistent policy implementation, and unclear chains of command.

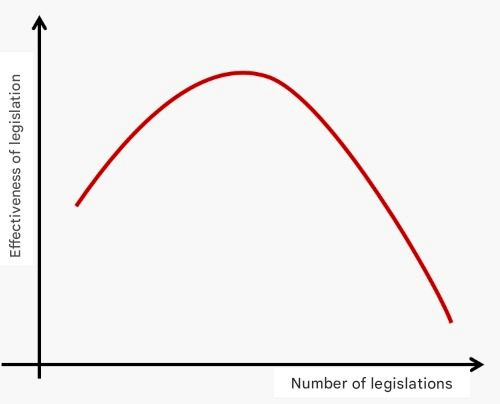

Regulatory effectiveness tends to decline once a saturation point is reached (see Figure 1 below). Administrative burdens are not only a function of the number of existing laws; they also include how policies are implemented. Key challenges include:

- Complex payment systems for services (stamps, cash, local or foreign currency, bank cards, digital platforms).

- Service quality, including not just customer care but also the time and psychological toll of navigating public systems imposed on individuals, particularly amid Cuba’s prolonged economic crisis.

- Complex forms and documentation, including difficulty identifying the required paperwork and submitting it—often requiring in-person visits to government offices.

- Great discretionary power granted to public servants, leading to arbitrariness in making decisions that directly impact citizens’ lives.

Figure 1: Hypothetical curve of legislative effectiveness in an overregulated context

Source: Author.

The nationalization of Cuba’s economy in the 1960s was accompanied by the expansion of a bureaucratic structure designed to manage a hyper-centralized and vertical economic model. Cuban cinema has captured the complexity of bureaucratic burdens with humor and wit. “Death of a Bureaucrat”, directed by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, portrays one of the many effects of these burdens on the relationship between citizens and public administration, highlighting the unnecessary overregulation of procedures that, by their very nature, should not be complicated.

The literature on the subject argues that some administrative burdens exist precisely to discourage citizens from pursuing or accessing goods or services to which they are legally entitled.

Another key issue is what is regulated and how. In Cuba, public policies are enacted primarily through decrees and decree-laws issued by the Council of Ministers and the Council of State, respectively.[7] Ministries have the discretionary power to issue directives and regulations that, in practice, impact the economic performance of the system through their influence on the operations of both state-owned and private companies, domestic and foreign. In the case of economic policy, it should not only articulate clear goals but it should also define realistic targets and contain evaluation metrics.

Administrative burdens in this overregulated legal environment obstruct everyday activities. Cubans often face inconsistent, fragmented, and plainly contradictory regulations. These challenges are evident not only in the sheer volume and type of legislation but also in vague legal language, frequent rule changes, unclear deadlines, and instances where even well-defined deadlines are suspended in legal limbo.

Impacts of Administrative Burden and Overregulation

Together with Cuba’s ongoing social and economic crisis, this regulatory environment fosters a thriving informal market for administrative services, where bureaucratic processes are bought and sold. This market corruption includes influence peddling and unauthorized income generation by public employees.

Some international organizations compile corruption indices based on various data sources. However, in Cuba, it is difficult to validate these figures due to restricted access to public sector information. Still, these reports consistently highlight high levels of petty corruption, particularly in routine public administration.[8]

![ChatGPT. (June 7, 2025). More patience [Image generated by IA]. OpenAI. https://chat.openai.com/ Image of man dressed in blue suit and tie pleading with a bureaucrat behind a desk dressed in green](/sites/horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/files/styles/cu_crop/public/content/T2.jpg?itok=xOK86o1g)

Administrative burden, when combined with overregulation, tends to exclude the most vulnerable populations from accessing essential services. This generates not only economic and social harm but also political damage, eroding citizens’ trust in government institutions. Increasingly, Cubans view the bureaucracy not as a facilitator of solutions but as an obstacle.

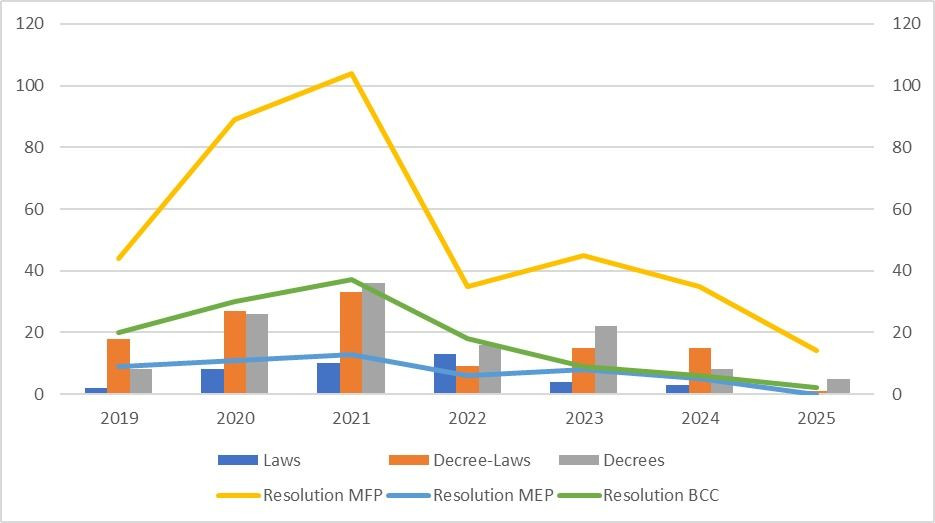

During periods of economic reform, legislative activity spikes. Between 2019 and mid-2025, 279 new laws, decrees, and decree-laws have been passed—excluding ministerial resolutions and internal directives.

Some policies, especially those governing state enterprises, have been revised at least seven times since 2018. Such volatility creates uncertainty, raises costs, and increases perceived country risk for both domestic and foreign investors. This comes on top of resource shortages, banking restrictions, and an ongoing energy crisis.

Figure 2: Number of legislative acts approved in Cuba (2019–2020)

Source: Author, based on methodology by Pérez Martín (2017), adapted in Bahamonde (2024) and Bahamonde & Mesa (2025).

Finally, maintaining such a vast bureaucratic apparatus consumes substantial human and financial resources. A more efficient public administration would free up resources for productive activities and service delivery. In 2023, Cuba’s government spending reached approximately 39% of GDP,[9] placing it second globally—only behind Ukraine, which is at war.[10]

Final Thoughts

In the Cuban legislative environment, at least two elements converge that impact the effectiveness of public administration: unnecessary administrative burdens and overregulation.

Administrative burdens stem from complex procedures, ambiguous regulations, and the rise of an informal market for bureaucratic services, enabled by the ambiguity of laws lending themselves to differing interpretations.

This environment gives public officials wide latitude to act unilaterally. Navigating Cuba’s public administration system is time-consuming, emotionally exhausting, and resource-intensive.

Overregulation compounds these burdens, making them even more costly. Public policy must be coherent and aligned with clearly defined goals. Legislation should serve a regulatory function – not one that limits economic activity- to support the country's economic development.

Ultimately, both overregulation and excessive administrative burdens weaken the relationship between citizens and the state, reduce trust in institutions, and increase the perception of country risk.

[1] Herbert A. Simon, Administrative Behavior. A Study of Decision-Making Process in Administrative Organizations, Forth (New York: Free Press, 1997).

[2] Donald Moynihan, Pamela Herd y Hope Harvey, "Administrative Burden: Learning, Psychological, and Compliance Costs in Citizen-State Interactions", Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 25, no.1 (2015): 43-69, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muu009.

[3] Tamarys L Bahamonde, "The Cuban State Decision-Making Process during Reforms (1990-2018)" (Doctoral Dissertation, Delaware, USA, University of Delaware, 2024), 9-10, https://doi.org/10.58088/q8qy-br02.

[4] J. C. Scott, Seeing Like a State. How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998), 79; Antón L Allahar y Nelson P Valdés, "The Bureaucratic Imperative", The CLR James Journal 19, no. 1 (2013): 392-422, https://doi.org/10.5840/clrjames2013191/219.

[5] Juan Valdés Paz, El espacio y el límite. Estudios sobre el sistema político cubano [Scope and Boundaries. Studies About the Cuban Political System] (Havana: Ruth Casa Editorial, 2009), 57; Bahamonde, "The Cuban State Decision-Making Process during Reforms (1990-2018)", cap. 5.

[6] Vilma Hidalgo de los Santos, "Políticas macroeconómicas en Cuba. Un enfoque institucional [Macroeconomic Policy in Cuba. An Institutional Approach]», en Transformaciones económicas en Cuba: Una perspectiva institucional (Economic Transformations in Cuba: An Institutional Approach), ed. Mario Bergara y Vilma Hidalgo (Havana: Facultad de Economía-Universidad de La Habana. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales-Universidad de la República-Uruguay, 2016), 79-122; Anamary Maqueira y Juan Triana, "El sector no estatal desde la perspectiva institucional [The Non-State Sector from an Institutional Perspective]", en Transformaciones económicas en Cuba: Una perspectiva institucional (Economic Transformations in Cuba: An Institutional Approach), ed. Mario Bergara y Vilma Hidalgo (Havana: Facultad de Economía-Universidad de La Habana. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales-Universidad de la República-Uruguay, 2016), 315-50; Nancy Quiñones y Michel Trujillo, "Cuba: Incentivos e Instituciones para la inserción externa desde 1990 [Incentives and Institutions in the Insertion of Cuba in the International Market since 1990], en Transformaciones económicas en Cuba: Una perspectiva Institucional (Economic Transformations in Cuba: An Institutional Approach), ed. Mario Bergara y Vilma Hidalgo (Facultad de Economía-Universidad de La Habana. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales-Universidad de la República-Uruguay, 2016), 213-48.

[7] Amalia Pérez Martín, "El lugar del derecho en el orden político de la reforma económica en Cuba: entre la república y el reino" [The Role of Law in the Political Order of Economic Reform in Cuba: Between the Republic and the Kingdom], Cuban Studies 45 (2017): 46-65, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44782928; Bahamonde, "The Cuban State Decision-Making Process during Reforms (1990-2018)".

[8] Mathias Bak, "Cuba: Overview of Corruption and Anti-Corruption", U4 Anti-Corruption Helpdesk (U4 Anticorruption Resource Center, 4 de noviembre de 2019), 4-5, https://www.u4.no/publications/cuba-overview-of-corruption-and-anti-corruption.pdf.

[9] ONEI, 2022. Statistical Yearbook. Cuba, 2023.

[10] "Government Spending, Percent of GDP by Country, around the World", TheGlobalEconomy.com, accessed May 28, 2025, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/Government_size/.

![ChatGPT. (June 7, 2025). Mountains of papers, resigned faces [Image generate by IA]. OpenAI. https://chat.openai.com/ A man with two cigars in his pocket accepting applications from a large line of people](/sites/horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/files/styles/cu_crop/public/content/pics/TLB%20Imag%C3%A9n%201.jpg?itok=R_YU963O)