The “Monetary Reordering” and Exchange Rate Distortions

As it faces problems created by untimely and poorly conceived measures at its worst moment of the last three decades, Cuba must correct course and adopt more realistic policies.

For many years, Cuban economists had proposed the elimination of the dual currency system with multiple exchange rates. Not until 2011 at the VI Congress of the Cuban Communist Party was this measure included in the Economic and Social Policy Guidelines it issued.

It would take another 10 years for the so-called “monetary reordering” effort to be implemented. Theoretically, it would have created a unified monetary system that could allow the national currency to reflect the prices in the domestic economy in relation to the international economy.

However, in reality what was implemented was an exchange rate unification through a 2,300% devaluation of the official exchange rate of the Cuban peso against the US dollar, establishing the new rate as the same one that already existed in CADECAs (government currency exchange houses for Cuban recipients of hard currency) before the pandemic intensified the economic crisis: 24 Cuban pesos to one US dollar.

The new policy, adopted at perhaps at the worst possible moment—when there was a lower supply of foreign currency due to the pandemic’s depression of international tourism—was preceded by the announcement of the opening of stores that the public could only access with bank deposits of freely convertible currencies. Although the dollar and other currencies accepted by the Central Bank of Cuba do not circulate in bank notes, they function as a means of payment similar to demand deposits and, strictly speaking, are part of the money supply. And since they are not converted into Cuban pesos, they function as parallel currency. Thus, the new monetary policy and its implementation have led to a partial re-dollarization of the economy.

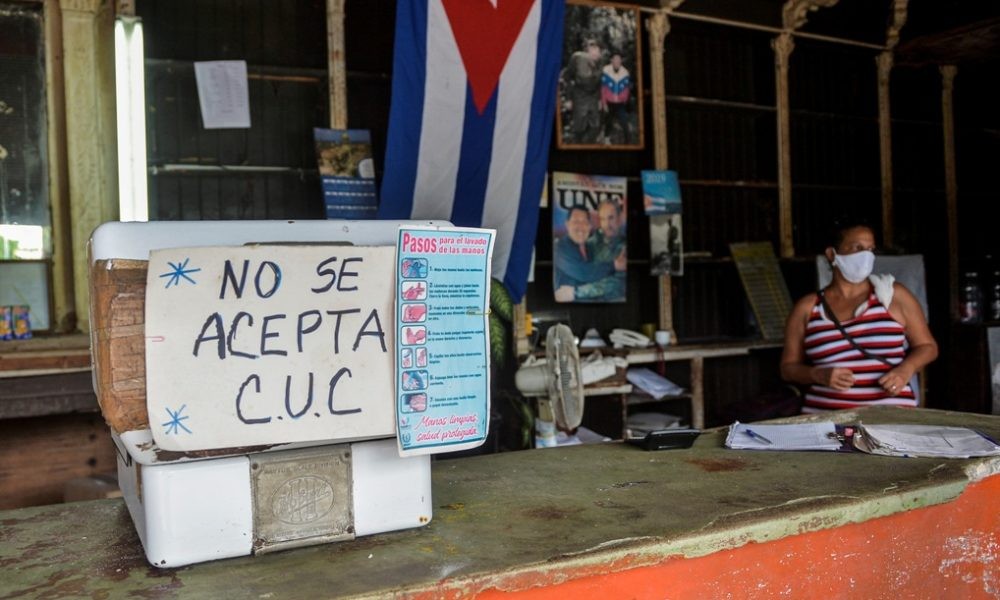

The so-called convertible peso (CUC)––which was by the time of the adoption of the new policy no longer convertible––was appropriately eliminated. However, this “secondary currency” had been created by the government to serve as an equivalent to the US dollar, in order to avoid the circulation of the U.S. currency. Now, the US dollar has retaken its place in circulation among a segment of the market in the form of electronic deposits.

The “Monetary Reordering”

The Cuban authorities named these new monetary policy measures listed below the “Monetary Reordering”. They consist of:

- eliminating the CUC;

- establishing a new official devalued exchange rate for the Cuban peso (CUP); and

- reforming prices, wages and pensions.

The authorities assumed that these measures would reorganize successfully the monetary and exchange rate chaos that had plagued the country for decades.

In revising the salaries of those working for the state, the government established 32 scales, with a minimum monthly salary of 2,100 pesos (87.50 USD) and a maximum of 9,510 pesos (396.25 USD). Most pensions, which had been previously fixed at between 280 and 500 pesos per month, were now set below the minimum wage, in a range from 1,528 and 1,733 pesos. Pensioners with incomes above 500 pesos per month would receive 1,528 plus whatever they previously earned.

Consequently, a retiree with a pension of 500 pesos now receives 1,733 pesos, while another who had received a pension of 501 pesos now receives 2,029 pesos. In other words, the gap for those two groups of pensioners grew from that of one peso to 296. Moreover, as the readjustments were made, older retirees were set to receive very small pensions, at levels close to the minimum pension.

The “monetary reordering” established a price of 1,528 pesos for a basic basket of goods and services guaranteed monthly to all citizens. The methodology for arriving at that figure is unknown, and, in reality, it is well below current needs. The original calculation by Cuban officials was that prices would increase by only 1.6 times. Later, they announced that private enterprises could only increase prices threefold. On the other hand, they announced that state salaries would increase on average by 490% and pensions would increase fivefold.

However, the reality is that since the crisis of the 1990s, the gap between the population’s income levels and the cost of living has increased considerably. The salary and pension increases carried out to date are substantially lower than what is currently required to attain minimal survival conditions.

In September 2021, the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI) published its report on inflation, according to which the variation in the consumer price index—which includes 298 items that represent more than 90% of household spending—was 59.66% in 2021 and 69.37% on a cumulative year-on-year basis. The greatest increases in costs have been in transportation, housing services, and food and non-alcoholic beverages.

In the National Assembly session held last October 27, Marino Murillo Jorge, head of the Commission for the Implementation and Development of the Economic Policy Guidelines, acknowledged that inflation had increased more than expected, which had led to an increase in the real value of the basic basket of goods and services from the originally projected national average of 1,528 to an actual average of 3,250 pesos in Havana and 3,057 pesos in the eastern provinces. As a practical matter, all retirees and workers with pensions and salaries at the lower income scale receive less income than those values for the basic basket of goods and services. The price increase has been such that the cost of the basic basket of goods and services in the most populous areas of the country is close to the average monthly salary, which was established at 3,838 pesos.

The Overvaluation of the Peso in the Official Exchange Rate

In conceiving its “monetary reordering”, the Cuban government bet on a system of fixed exchange rates––with a new overvalued Cuban peso––in exchange for which the Central Bank of Cuba cannot guarantee the sale of the foreign currency. Consequently, the institutional exchange market has disappeared and an underground market has been revitalized in which the values of foreign currencies exceed the official rates several times over.

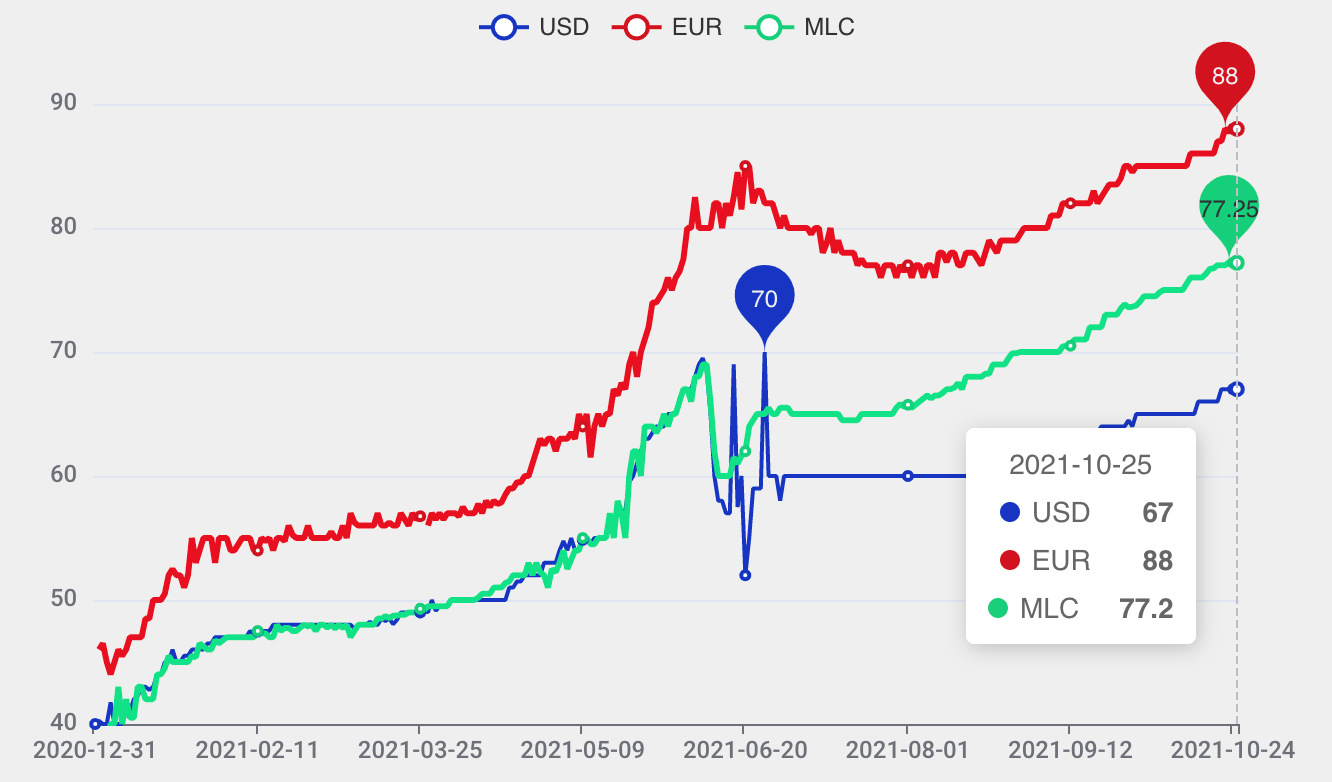

Graph 1. Evolution of the exchange rate of the Cuban peso (CUP) in the informal market. Unit: Cuban pesos for one dollar in cash (USD), one euro (EUR) or one dollar deposited in bank accounts in freely convertible currency (MLC)

Source: El Toque

In the absence of official government data and a transparent market, the digital publication El Toque has created a “representative” indicator of the exchange rate in the informal market, of US dollars in cash (USD), euros (EUR), and so-called freely convertible currency (MLC). The last of these currencies are actually bank deposits in dollars that are currently being traded at a value exceeding the cash USD value since the date the Central Bank adopted the policy of not accepting deposits of dollars in cash in MLC bank accounts.

Graph 1 shows the upward trend of the three variables in 2021, including for USD in cash despite the fact that its value peaked on June 24th, then stabilized and then began to rise again. The trajectory of these currencies is an indication that there is insufficient public confidence in the national currency (the Cuban peso): it is not fully fungible in Cuba because not all goods and services can be acquired with it.

However, in foreign trade and international transactions, the official overvalued exchange rate for the Cuban peso does work, because the value set by the authorities exceeds that reflected by the market; that is, it is valued at more than it should be valued, by market conditions. That gap, in the case of a USD in cash, which has the smallest positive slope, has increased from 166% in early January 2021 to 279% in October of that year.

It could be said that the values attained by foreign currencies in the Cuban market reflect an exceptional situation due to the drop in tourism, remittances and export earnings given the pandemic. However, this is how markets work and similar trends can be observed in many Latin American countries. The difference is that most of these countries use flexible exchange systems in which the exchange rate fluctuates daily in a transparent foreign exchange market that makes the existence of an underground market unnecessary or rare.

In contrast, Cuba opted for a fixed and overvalued exchange rate for the Cuban peso, resulting in a powerful Cuban underground exchange market, which ignores the established exchange rate and renders it useless. This also creates a powerful attraction for currency asset holders to continue to prefer the parallel underground market to the institutional market, even in the event that a fluctuating exchange market is reestablished in the future.

The overvaluation of the national currency has harmful effects on the competitiveness of exportable goods and services because it makes them more expensive. For example, aside from the costs attributable to the particularities of the Cuban foreign trade system, including the prices state companies charge for their services to effect the foreign trade, if the export price of a product in Cuban pesos were 2,400 CUP, that product should be valued at 100 USD internationally.

However, if there existed a fluctuating market exchange rate for the Cuban peso, that same product could be sold at 35.82 USD, making it very competitive internationally. The exporter would willingly receive the 2,400 CUP for the product because those CUPs actually could be used to acquire goods and services in the domestic market, including imports.

Similarly, if the product’s international average price is 100 USD, and if a fluctuating market exchange rate were used when making the sale at that price, the exporter would obtain 6,700 CUP instead of 2,400, which is clearly beneficial to it, as long as the devaluation rate does not exceed the rate of inflation.

Nonetheless, in Cuba, none of this works. Because CUPs must be exchanged at the government official rate and not the market rate, the state is forced to “stimulate” the exports of small and medium-sized entrepreneurs and cooperatives, allowing exporters to keep 80% of their income in the form of foreign currency deposits in the new dollarized market.

Necessary Changes

Facing problems created by untimely and poorly conceived “monetary reordering” implemented at the country’s worst moment of the last three decades, Cuba must correct course and adopt more realistic policies, especially after the reopening of the tourism sector. These changes should include the following components:

- Establish the Cuban peso’s complete sovereignty for all domestic transactions, eliminating freely convertible currency (MLC) stores and restoring full internal convertibility.

- Abandon the fixed exchange system and replace it with a flexible exchange rate, which might temporarily require Central Bank intervention to contain speculative pressures.

- Establish a transparent foreign exchange market in which supply and demand of foreign currency and Cuban pesos can freely interact.

- Allow the opening of branches of foreign commercial banks, under appropriate supervision of the Cuban financial system authorities, so that savings abroad by Cubans can be channeled to facilitate credit for domestic investment and consumption, particularly because of the clearly insufficient gross domestic savings rate in Cuba.

- Liberalize foreign trade, eliminating the state monopoly and allow for the operation of commercial and management companies of all kinds.

These measures would allow for a profound reform of the monetary and currency exchange system, which, in principle, would eliminate the distortions generated by the so-called “monetary reordering” and enable a more effective connection between the national and international economies. It should begin with product prices that result from free-market competition.

Obviously, only the necessary changes in monetary and currency exchange matters are addressed here, which are far from sufficient to put the Cuban economy on a path toward sustained growth.

Mauricio De Miranda Parrondo is a Cuban economist. He has a doctorate in International Economics and Development from the Complutense University of Madrid, Spain. He is a professor in the Department of Economics of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Cali, Colombia. Professor de Miranda Parrondo is editor and co-author of several books and author of chapters in books and articles on the Cuban economy. He is a visiting researcher and lecturer at various research centers and universities in America, Europe and Asia.