Cuba: Ten Consecutive Years of Macroeconomic Deterioration

The expansion of dollarization in Cuba may bring some stability to specific sectors, but it can also deepen economic segmentation and increase inequality.

Since the second half of the last decade, the Cuban economy has undergone a steady deterioration, adding to the structural distortions and unresolved social problems that date back to the 1990s.

An analysis of key macroeconomic indicators shows that the current economic crisis began to take shape well before the pandemic’s impact. Macroeconomic metrics reveal a continuous decline starting in 2016.

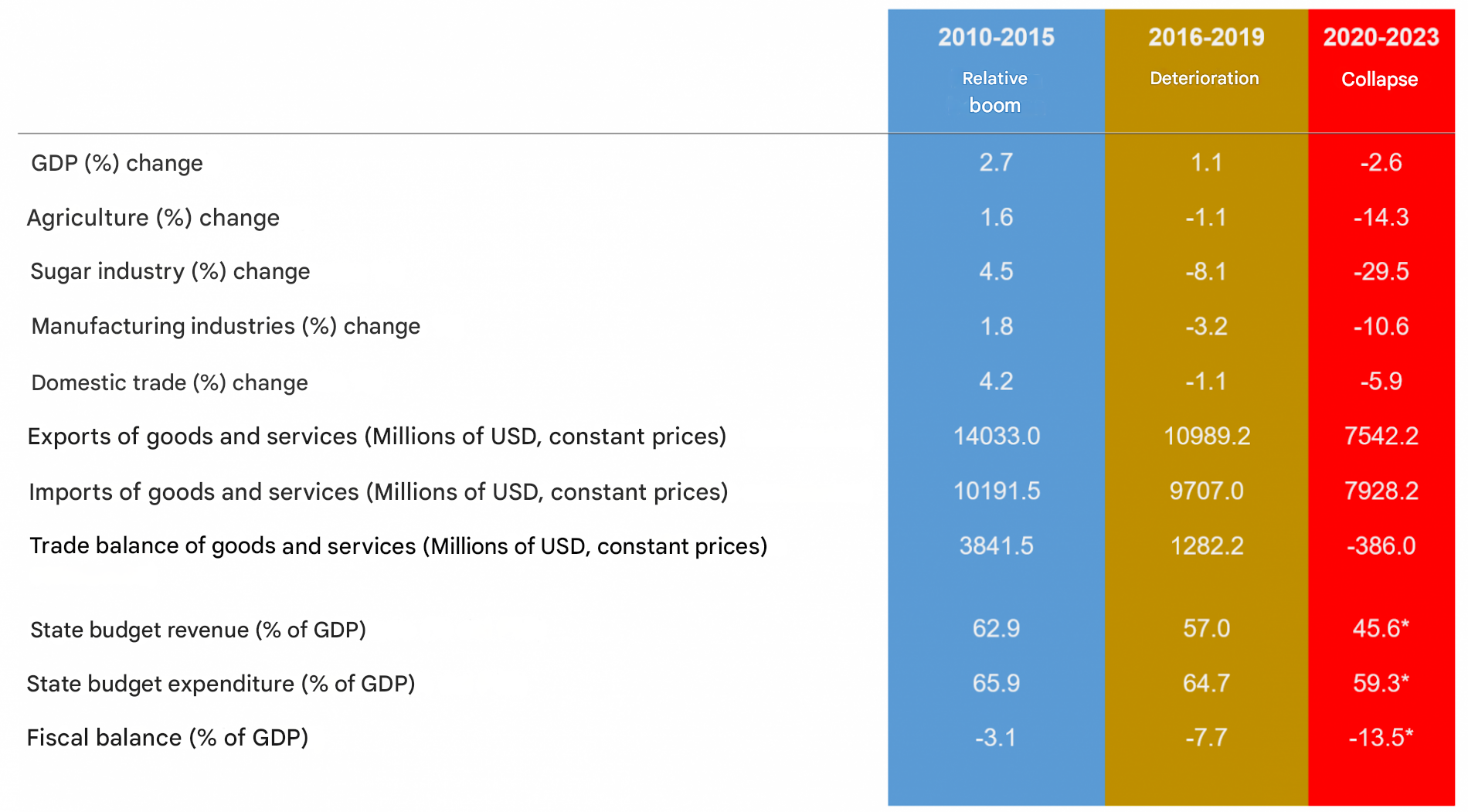

Table 1 summarizes the average values for gross domestic product (GDP) growth, selected productive sectors, foreign trade, and the State budget, illustrating this contracting and imbalanced macroeconomic scenario. In the evolution of indicators since 2010, three distinct stages can be identified, with turning points in 2016 and 2020.

Table 1. Cuban Macroeconomic Indicators 2010–2023

(average values by period)

Source: Author, based on data from the ONEI Statistical Yearbook.

* calculated with data up to 2022

The Decline in Production and the External Sector Go Hand in Hand

Between 2010 and 2015, Cuba’s GDP grew at an average annual rate of 2.7%, in a context of relative external prosperity. Agriculture, the sugar industry, and manufacturing industries increased the production of goods, though at modest rates. Domestic trade rose during this period at an annual rate of 4.2% (see Table 1).

This performance was driven mainly by agreements with Venezuela, including the receipt of oil under favorable financial conditions, the sale of Cuban professional services—especially medical personnel—pharmaceutical exports, and increased investments.

The easing of sanctions at the end of Obama’s second term and Raúl Castro’s reforms boosted tourism, remittances, and the small-scale private sector.

Exports of goods and services averaged 14.033 millions in US dollars (USD). Imports averaged 10.192 billion USD, generating a significant trade surplus of 3.841 billion USD annually.

Renegotiations of external debt with Russia, the Paris Club, and other bilateral agreements temporarily improved access to international financing. External financial leeway and the inflow of foreign currency allowed GDP growth to be sustained, reaching a peak of 4.4% in 2015.

During the period 2016–2019, the economy began to show troubling signs of fragility. GDP growth slowed to an average of 1.1% annually amid the Venezuelan crisis, falling oil prices, and tightening U.S. sanctions under the first Trump administration.

The end of the international “commodity boom” indirectly affected the Cuban economy, despite the fact that services and tourism have a greater weight than raw materials in its productive structure and exports. This impact was due to Cuba’s close ties to the Venezuelan economy and trade agreements dependent on the price of oil.

Exports fell to an average of 10.989 billion USD, and imports to 9.707 billion USD, drastically reducing the trade surplus to just 1.282 billion USD annually — a decline of 66.6% compared to the previous period.

The external contraction directly affected Cuba’s foreign currency earnings used to finance investments, as well as the availability of inputs and financial flows for the ongoing operation of the productive sectors. Agriculture, the sugar industry, and manufacturing industries showed negative average annual variation rates during the period, with sugar being the most affected at -8.1%.

Since then, greater shortages in consumer markets became evident. Domestic trade declined at a rate of 1.1%. In 2019, GDP had already entered recession territory with a decrease of 0.2%, and difficulties in meeting international financial commitments became more apparent.

The outbreak of the pandemic, hitting an already weakened economy, caused a GDP contraction of -10.9% in 2020, without a sustained and sufficient recovery afterward. The economic collapse is evident in double-digit annual contractions in the main sectors responsible for goods production. Agriculture declined at an annual rate of -14.3%, and manufacturing industries by -10.6%.

The continued collapse of the external sector is linked to the contraction in production. Between 2020 and 2022, the average GDP variation was -2.6%, while exports and imports fell by 31% and 18%, respectively, averaging 7.742 billion USD and 7.928 billion USD.

The trade balance shifted to a deficit, registering an average annual trade deficit of -386 million USD, reflecting the worsening financial restrictions under which the Cuban economy has been operating since the pandemic. By 2023, GDP remained 10% below pre-pandemic levels.

To the external factors explaining the collapse, the failure of the “Tarea Ordenamiento” (Monetary Reordering) must be added. This reform aimed to unify the currency system but resulted in higher inflation, a loss of purchasing power of the peso, and new distortions in relative prices. The financial crisis worsened, with defaults on external debt, breaches of agreements with foreign investors, banking illiquidity, and an expansion of the informal foreign currency market.

The GDP contraction increased the structural dependence on imports and foreign currency, creating pressures on the parallel market due to the lack of official liquidity. The absence of structural reforms has prolonged the crisis and undermined both domestic and international confidence in economic policies and authorities.

During Raúl Castro’s second term (2013–2018) and the early years of Díaz-Canel’s presidency, no comprehensive transformations were made to the economic model or institutions. The micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), which emerged in 2021, have energized certain consumer markets and generate employment and income for families. However, their contribution to productivity and GDP is limited by the restrictive regulatory framework in which they operate, as well as by financial and currency risks and distortions that discourage reinvestment and greater private investment.

Cuba has not managed to develop an international integration alternative to the model based on dependence on Venezuela and the export of medical services. Tourism is not growing despite millions invested in hotels; its competitiveness is undermined in an economy where there is a shortage of everything and power outages have become normalized.

Decapitalization is evident across nearly all sectors and infrastructures. Massive emigration irreversibly affects all areas of productive and service activities. The agricultural and energy crises worsen the shortages. Sugar production is at historic lows, while the domestic manufacturing industry is practically disappearing under the inefficient monopoly of the state-owned enterprise.

Fiscal Imbalances and Their Consequences

The worsening of macroeconomic imbalances is evident not only in GDP and the external balance. Fiscal data shown in Table 1 (above) clearly identify the evolution of the fiscal deficit as a percentage of GDP, which is key to understanding the monetary instability accompanying the current crisis.

During the period 2010–2015, public revenues averaged 62.9% of GDP, while public expenditures averaged 65.9%, resulting in a contained fiscal deficit of -3.1% of GDP. Fiscal prudence during these years was supported by an external environment that allowed for earning foreign currency income and financing for the productive sector and public spending.

In the following period, 2016–2019, the fiscal deficit widened significantly, with revenues averaging 57.0% of GDP and expenditures at 64.7%, resulting in an average deficit of -7.7% of GDP. The larger fiscal gap reflected economic deterioration, the fall in exports, and the paralysis of reforms, which reduced the State’s capacity to generate revenue to offset its expenses.

The situation became critical between 2020 and 2022, with fiscal revenues falling to 45.6% of GDP while expenditures remained high at 59.3%, resulting in an average fiscal deficit of -13.5% of GDP. This alarming fiscal imbalance was again a consequence of the collapse in economic activity but was worsened by the pandemic and the failed monetary reform. In 2020, the deficit peaked at -17.7%, primarily financed by monetary issuance. This triggered inflation and a parallel depreciation of the peso.

In 2024, the government began attempting to reduce the budget deficit, but without implementing measures that significantly improve the efficiency of public spending or the profitability of the state-owned business sector.

The fiscal measures adopted have been partial and regressive, such as increases in prices and tariffs. The monetization of the persistent and disproportionate gap in state finances has shifted the cost of adjustment onto the most vulnerable sectors, eroding the purchasing power of most households’ incomes and savings.

The absence of a stabilization program and structural reforms has hindered any potential renegotiation with international creditors, deepened financial isolation (beyond the impact of sanctions), and pushed further away the prospects for productive recovery.

What Do the Most Recent Data Show?

The government confirmed that in 2024 the GDP declined again, marking two consecutive years of negative growth and contractions in four of the last six years. The limited data available through April 2025 indicate that macroeconomic imbalances and the production crisis persist. In the first months of the year, tourist arrivals have been falling at rates between 25% and 30%.

Power outages continue unabated. The energy situation remains one of the main constraints to recovery. In 2024, electricity generation dropped significantly compared to previous years, and during February and March 2025 daily deficits exceeded 1,200 MW, affecting production and services nationwide. The installation of solar parks has progressed very slowly.

On the fiscal front, the government reported a public deficit of 9 billion pesos in 2024, which would represent a 39% reduction compared to the approved budget.

For 2025, the government budgeted a fiscal imbalance very similar in absolute terms to the 2024. Although fiscal adjustment has partially contained the imbalance, the amounts remain unsustainable, representing more than 10% of GDP, and continue to be financed by money issuance without productive backing, which maintains pressure on inflation and the informal exchange rate.

Official inflation closed 2024 at 25%, slightly lower than the 31% recorded in 2023. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) from the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI) showed an upward trend in the early months of 2025, with monthly rates of 2.1% in January and 2.75% in February, then falling to 1.22% in March, leaving the annual inflation rate at 20.6%.

The CPI basket underrepresents private and informal markets, where a large part of the population must turn to buy food, medicine, and other goods and services. Therefore, the real inflation rate is higher than the official figure.

Although inflation has decreased in annual comparative terms, it remains high, highlighting that the economy still faces significant imbalances that push prices upward in consumer markets. This continues to reduce the purchasing power of wages and pensions and worsens the poverty situation for many families.

The informal currency exchange market remains the main reference for the value of the Cuban peso. Since March 2025, the peso’s depreciation has accelerated.

In April 2025, the representative exchange rate for the US dollar reached 365 Cuban Pesos (CUP), and for the Euro, 380 CUP (while official rates remain fixed at 24 CUP and 120 CUP, respectively). Cryptocurrencies have also increased in value, with the USDT (or Tether, a cryptocurrency pegged to the US dollar) at 400 CUP, reflecting Cubans’ preference for more stable assets amid exchange rate uncertainty and the depreciation of both the CUP and the MLC[1].

The government has announced new measures to reorganize the currency exchange market, including a floating rate for the retail market and increased partial dollarization. Without addressing the underlying imbalances and distortions in the economy, the continued coexistence of the informal market and official exchange mechanisms seems inevitable in the short to medium term.

Dollarization has intensified with the increase in points of sale in foreign currency and the expansion of payment instruments denominated in US dollars. While these measures may provide some stability in specific sectors, they also deepen economic segmentation and increase inequality.

In summary, the most recent data reaffirm the continuation of the period of economic collapse that began in 2020, but which dates back to a decade-long macroeconomic deterioration.

[1] The MLC in Cuba is a digital currency backed by U.S. dollars, used through magnetic cards to purchase goods in specific stores, which are generally better stocked than those operating in Cuban pesos.

![ChatGPT. (2025, May 9). The dominoes of the Cuban economy [AI-generated image]. OpenAI. Image of falling dominoes with the titles "high fiscal deficit," "monetary issuance," "inflation," "loss of purchasing power," "poverty"](/sites/horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/files/styles/cu_crop/public/content/PVA%20Imagen%201%20Ingles%202.jpg?itok=xr4tOZQn)