Migration Crisis, the Economy and Sanctions

People with an entrepreneurial spirit do not stay in Cuba, dealing a sharp blow to an extremely elderly society that has shown worrisome trends in labor market demographics.

The original Spanish version of this article was posted on August 14, 2022

On April 21, 2022, on the eve of the Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles, officials from the United States and Cuba met in Washington, DC, to discuss migration issues in the highest-level talks between the two governments since President Joe Biden took office.

The main outcome of the talks, which took place as a record number of Cuban migrants have been crossing into the United States from Mexico, appears to be a commitment by both governments to ensure compliance with the U.S.- Cuba Migration Accords, last updated in 2017 during the Obama administration. Just weeks after the talks, the White House announced that it would partially lift some of the sanctions on the Cuba.

This is a positive and constructive step, but insufficient to resolve the current migration crisis, as evidenced by simple arithmetic: According to the Migration Accords, up to 20,000 visas should be granted per year, but the annualized rate of Cuban emigration to the United States exceeds 100,000. In 2022 through August 22, an estimated 150,000 Cuban migrants crossed the southern border.[1] The crisis has underlying determinants in Cuba and is the result of the economic sanctions themselves.

The Cuban economy was one of the hardest hit by the pandemic in Latin America. It has recovered very little in 2021 and 2022, and has one of the highest inflation rates in the region,[2] influenced by the asymmetric impact of the sanctions on the living conditions of Cuban families,[3] as well as the incomplete reforms of its failed economic model.

In recent weeks, there have been frequent electricity cuts, and the consequences of the decapitalization and technological obsolescence of the energy sector infrastructure, impacted by the lack of foreign currency needed to finance even minimal maintenance, are beginning to be felt.

Another discouraging factor for young people is the Cuban government’s negative reaction to the protests of July 11, 2021, confirming that there is virtually no space for real political participation toward change in the country. Although economic concerns could be considered the main cause of the new migratory wave, the influence of the deteriorating political climate on the island cannot be overstated.

Impact on the Workforce

In the short term, allowing emigration as an escape valve may seem beneficial tor the Cuban government. Cubans have no Illusions of progress on the island; people are emigrating rather than pushing for change—where change seems both economically and politically impossible. Many of those who bet on the opportunities that opened up during the Raúl Castro and Obama era are leaving. Emigration takes with it human capital, financial resources and accumulated experience. People with an entrepreneurial spirit do not stay on the island, where they might innovate and create companies and jobs. Instead, they take their talent elsewhere.

Brain drain is always a blow to the potential economic growth of a country, but it is much more acute when it occurs in an extremely elderly society like Cuba’s, which has been showing worrisome trends in labor market demographics.

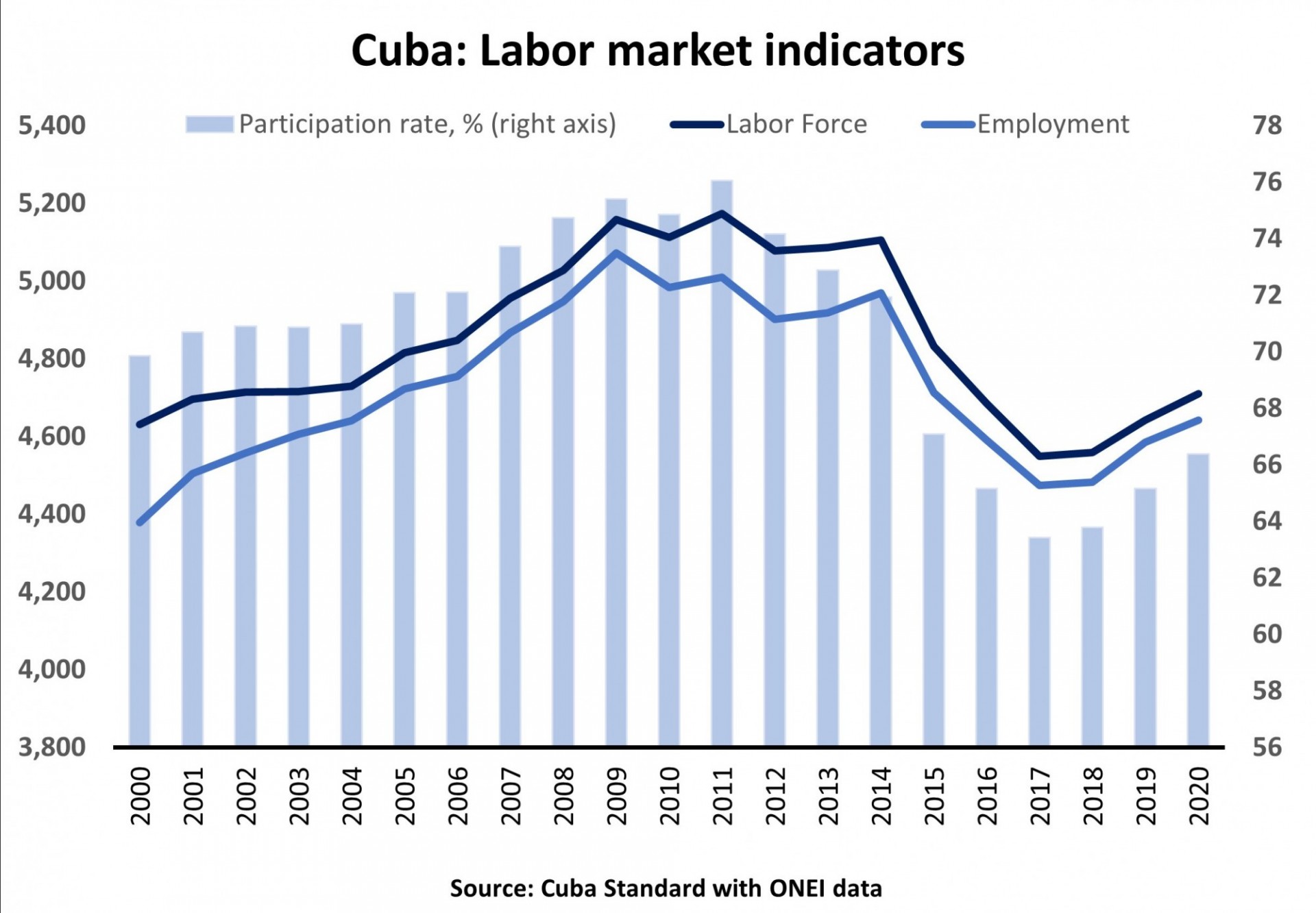

The total Cuban labor force peaked in 2011 at 5.2 million people, which at that time represented 76% of the working-age population (participation rate). Since then, both indicators have fallen sharply, reaching a low in 2017, followed by a marginal recovery. In 2020, the labor participation rate was 10 percentage points lower than in 2011. The labor force contracted by almost half a million people from 2011 to 2020. A similar trajectory has occurred in the employed population (see Figure 1). These data do not yet reflect the impact of the current migratory wave[4]

In a blog post for ASCE (the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy), the late economist Ernesto Hernández-Cata studied the possible causes of this drop in the labor force participation rate.[5] The demographic trends also have unfavorable implications for the pension system, as analyzed by Carmelo Mesa-Lago, Carla Moreno and Stephen J. Kay in an article published this year in the journal International Social Security Review.[6]

On the other hand, emigration has a much greater economic impact when the economy is highly dependent on the labor force to produce food and other goods and services. Due to financing limitations and the impact of constant balance of payments crises, most Cuban economic sectors operate with a very low level of capital and technological development.

The impact of emigration on the labor market may not be immediately evident, given the current low productivity levels. However, it will be much more apparent when recovery is consolidated, tourism increases and workers are needed for the state and private economies to operate at full capacity.

The migratory wave has slowed economic recovery to pre-pandemic levels and reduced the potential aspirations of small- and medium-sized private enterprises, despite recent improvements in the legal framework. Once again, U.S. sanctions, given that they are partial determinants of the current economic crisis, have proved their counterproductive effects. Not only do the sanctions fuel the migration crisis on the southern border, they also spur the departure of entrepreneurs and young people who, having left the island, can no longer constitute a possible force for real change within Cuban society.

The Biden Administration’s Measures

In the midst of the island’s complex social, political and economic dynamics, President Biden has announced new measures to promote formal channels for family reunification, travel, remittances and support for the Cuban private sector.[7]

The Cuban Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MINREX) described the announcement as “limited steps in the right direction”. [8]

Certainly, the measures are not intended to return relations and economic exchange with the island to Obama-era levels.

In the short term, the measures offer partial relief to many families. Travel and remittances offer two sources of income that above all have an impact on household consumption and on sales and employment in the private sector. Given the magnitude of the crises and shortages in Cuba, any additional dollars can be considered a relief.

Nonetheless, the boost that Biden’s measures have the potential to generate in Cuban private enterprise is restricted by the moderate impact that can be expected on travel, given that individual trips and cruises are not permitted. In addition, Cuba remains on the list of countries that sponsor terrorism, hindering international electronic payments, which are essential for remittances to be received by Cuban families via a formal financial channel and at a lower cost.

The use of digital wallets, cryptocurrencies and P2P (peer-to-peer) transactions should be considered by the U.S. to facilitate electronic transfers, and the U.S. should allow Cuban nationals to participate in international exchanges (cryptocurrency markets). Eliminating obstacles for Cubans to conduct transactions involving U.S. banks is another measure for the White House to consider in order to facilitate operations through the conventional financial system.

Digital financial channels are also crucial for Cuban private entrepreneurs to be able to export, import and expand their activities into international operations. However, very little of what the White House has promised for the private sector seems feasible as long as Cuba’s small- and medium-sized enterprises continue to exist within a country designated by the U.S. as a sponsor of terrorism.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/03/world/americas/cuban-migration-united-states.html

[2] https://horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/news/inflation-cuba-and-economys-potential-recovery-part-ii

[3] See “The economic impact of U.S. sanctions on Cuba, 1994-2020,” https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/documento-de-trabajo/el-impacto-economico-de-las-sanciones-estadounidense-a-cuba-1994-2020/

[4] In recently published data of the 2021 Anuario Nacional, most employment indicators were left blank. The ONEI (Cuban national office of statistics and information) published tables in Chapter 7 of the Anuario with the following note: “The data referring to the active population, the rate of economic activity, the unemployed, and the unemployment rate for 2021 cannot be made available because the National Occupation Survey was not carried out.”

[5] https://www.ascecuba.org/explaining-fluctuations-in-cubas-participation-rate-by-ernesto-hernandez-cata/

[6] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/issr.12293

[7] https://www.state.gov/biden-administration-expands-support-to-the-cuban-people/

[8] http://www.cubadebate.cu/especiales/2022/05/16/declaracion-del-minrex-un-paso-limitado-en-la-direccion-correcta/