The Impact of a New Internet on the Cuban Public Sphere

The young people who mobilized in Cuba during the 2019 tornado are part of our first digital generation to apply the principles of technosociability.

Among the many analyses of the causes of the July 11 protests in Cuba, one has come up repeatedly: the impact of the Internet.

The Internet in Cuba has been configured in a mobile and dynamic way, used by various sectors and social agents with a variety of divergent interests. Discourses across the extremes of the political spectrum coexist online with a society whose very access to the “network of networks” has transformed it into a post-totalitarian, pluralistic space.

We are talking about an online civil society with communication tools at its fingertips that allow people to listen to others and, above all, to make themselves heard. It is also a network that is no longer used solely for consumption or recreation, but also as a tool for social change and a space to debate topics ranging from culture to the economy, and above all to move from the social to the political.

This article describes the role that the Internet has played in social dynamics before, during, and after July 11. This summer, the Internet in Cuba was rocked by hashtags and live broadcasts, the preferred tools of our incipient online society.

Virtual Reality Takes to the Streets

On a warm night in January 2019, an unexpected tornado swept through several municipalities in Havana. In less than an hour it left a bleak landscape in its wake, with half a dozen dead, more than 20,000 people displaced, and some 10,000 homes affected, of which 3,000 were totally destroyed, and tens of millions of pesos in material losses. Just one month earlier, Cubans had been authorized to access the Internet through mobile data technology, sparking a small and silent revolution in Cuba. Since 2014, one could only access the Internet through fixed connections or on the Cuban telephone company's (ETECSA) WiFi networks.

The island experienced a citizen mobilization around those affected by the tornado, driven by smartphones with newly acquired mobile data. The new communication facility first proffered images and then stories of what had happened, disseminated nationally and internationally. News and aid among neighbors and neighborhoods flowed much earlier than through the official channels. For the first time in the streets of Havana, a teenage couple could film and upload videos to Facebook or YouTube.

The connection speed and mobility enabled Cubans not only to contact their relatives and friends abroad through social networks and messaging applications, but also to use information and communications technologies (ICTs) as tools for socialization and citizen solidarity. Donations to the affected neighborhoods were managed through social networks, and thanks to 3G technology, the world witnessed it.

The mobilization around the tornado was followed by others. In April, there was a march against animal abuse. And then there was a march in defense of the rights of the LGTBI community, the first to be called for by organizations independent of the State and which ended with confrontations and violent arrests because the authorities considered the demonstrations illegal. Later, there were viral challenges that mobilized environmental groups to clean up coasts, rivers, and forests.

For their part, the official and independent media, as well as official and opposition political and cultural groups, have found on the Internet a space to disseminate their ideas, as well as a critical mass of mostly young urban users with average purchasing power. All of this has led, in just five years, to a critical point, a chaotic and varied polyphony on social networks that is completely unrelated to the bipolarity or monotony of traditional discourses.

From January 2019 to July 2021 we bore witness to the impact of access to the Internet in Cuba, largely inclined toward breaking down previously established norms and values in a chain reaction typical of periods of deep and accelerated changes in technological, socio-economic, and political structures. Social groups, of mostly young people, feeling disconnected from the old structures of social control, found in the digital space a natural habitat to express hope and indignation (Castells 2012).

They question the inner meaning of the institutions that represent them, which they view as incapable of taking on complex situations such as the pandemic and the deep economic crisis that affect their very existence.

On July 11, 2021, 7,700,000 Cubans—or 68% of the population—used the Internet: 6,000,280 used social networks (55.5% of the population). There were 6,140,000 active mobile lines, of which more than three million connected via mobile data during the prior semester. These users make up a new digital generation, born after the collapse of socialism in the USSR and the crisis of the 1990s. For example, the most active age group online is between 21 and 30 years old (52.8% of respondents to an online survey); 78.37% of users are under age 40.

The old “anomies” as structured by Émile Durkheim cannot explain current social movements such as protests in Cuba, in the narrow sense that Lorenz von Stein once put forth: “An aspiration of social sectors (classes) to achieve influence over the State due to inequalities in the economy.”

The 11J movement (named for the July 11 protests), as with the Arab Spring or the Spanish “15M” (March 15), are social movements that are born and evolve from “connected multitudes.” And although they recognize economic inequalities as essential, they are not framed by them but by a wide range of demands that range from minority rights to the environment. To this end, they naturally circulate from digital spaces to physical spaces, and vice versa, transforming into “intelligent masses” with a plurality of objectives, whether individual or collective, and impossible to quantify within traditional sociological metrics. This summer’s events in Cuba will configure that new hybrid territory that transcends the borders between the digital and the physical, as do the demands.

That is the connected and intelligent multitude that was heard on July 11, 2021 in San Antonio de los Baños, without violence nor acts of vandalism, only a crowd of networked individuals that inspired hundreds of other individuals on other streets and squares in Cuba by expressing the same demands and feelings. And if we look closely, they are not very different from the masses that did the same in Tunisia or Egypt a decade ago.

The Age of Interconnected Upheavals

This networked crowd can be defined for the moment as a digital citizenry that is enabled, through online devices, to connect, gather, synchronize, and mobilize around various objectives, moving from personal blogs to public squares at any given moment.

On July 11 we witnessed the incipient birth of an online social movement born of a tornado in 2019 and catalyzed by a pandemic in 2021.

The protests represented a metamorphosis of all those preceding social movements, adapted to our reality, but equally influenced by universal demands.

This online movement connects various collectives and multiple individuals—groups, institutions, and official organizations—with dissidents, minorities, and people who have been marginalized or discriminated against, as well as with the silent majority of a population hard hit by the worst economic and social crises since 1994, aggravated by an out-of-control pandemic and affected by the policies of the most recent two U.S. administrations, characterized by confrontation and belligerence.

But today’s population is very different from that of 1980 or 1994: it is more global, plural, and informed. Thanks to Internet access, today we see a variety of interests and objectives and a much higher level of information than during the 80s or 90s. Those who do not adapt will have trouble surviving in this new, more inclusive, explosive, and unpredictable social environment. This digital ecosystem allows for the exploration of multiple identities that go beyond the stereotypes expressed in those days: “revolutionaries,” “mercenaries,” and “confused” or “marginal” people.

Digital social networks act as stand-ins and unifiers for a variety of those with deep interests who have not found space to participate within the public sphere or in economic and political processes.

Technopolitics Makes Its Presence Known

Thus far we have described “connected masses,” “smart crowds,” and the “online society.” The concept of “technopolitics” has been widely used to reevaluate telecommunications and Internet (TIC)and summarize many of these ideas. Technopolitics is understood as the tactical and strategic use of technological devices (including social networks) for organization, communication, and collective action.

Technopolitics has manifested by taking over public digital, physical, and media spaces, capable of guiding distributed actions both in virtual networks and in the public square. It is an irreversible phenomenon. Networks have been used not only to build and reproduce collective action, but also to weave in the meaning of the action itself and create a transformative catalyst in different groups and social sectors, to narrate what happened, and to shed light on the no-longer-viable discourse of the extremes at the antipodes of reality. ICTs are reproducers of the deep personal motivations and the complexities of a particular social and political context with its intergroup and class relations and structural deficiencies.

In today's Cuba, technopolitics takes the leap to geographical spaces, revealing institutional shortcomings and inabilities to confront global issues such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The vertical models of traditional institutions, with their controls, hierarchies, ossified consensus and functionality, are recognized as inoperative in today's world.

When citizens do not find channels for political participation, institutional transparency, or any control over their leaders, they use social networks to organize and move from virtual to real spaces. Via that cybernetic public space that is the Internet, they are able to occupy real space and direct participation in public spaces, which they consider has been hijacked by professional politics, more attentive to reproducing the economic and media powers that uphold them than listening to the interests and solving the problems of the citizens who elect and legitimize them.

Technopolitics offers networked individuals a varied spectrum of transversal options according to their specific interests. And, as the use of ICTs on the island has shown, it is a process of continuous and multifaceted creation process - both transversal and cross-border. The Internet is therefore not just a tool but another battlefield for action and a terrain to be conquered or defended.

The Prolonged Battle for the Internet

This battle over hearts and minds occasionally includes the well-known blackouts or Internet outages, that is, an assault on the Internet by the State.

The website Access Now counted 155 internet blackouts in 29 countries in 2020. India, the most populous democracy in the world, was at the top of the list with 109 blackouts. In Latin America there were four blackouts: two in Venezuela and one each in Ecuador and Cuba. The official justifications for the Internet blackouts were public safety, political instability, out-of-control or violent protests, national security, and to control "fake news" or hate speech.

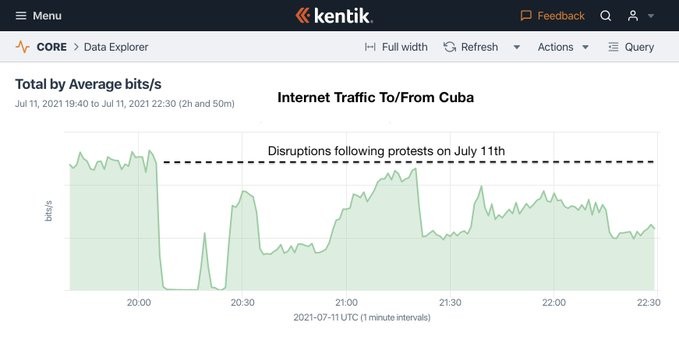

During the July 11 protests, the Cuban authorities disconnected the network a few minutes after President Miguel Díaz-Canel appeared on radio and television. The Internet outage lasted almost 45 minutes. After 5 p.m., traffic was erratic.

What really happened on that day and the following days were outages and disruptions to Facebook and WhatsApp and to encrypted messaging services such as Signal and Telegram. These outages can usually be bypassed by using a Virtual Private Network (VPN). There was also a severe slowdown in connection speeds. When speeds are reduced to less than 2G, only voice calls and SMS messaging are possible; high-data services such as social networks are inaccessible. The outages were not caused by a lack of electrical power.

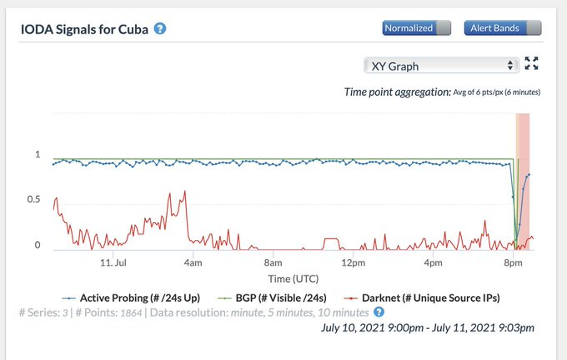

The following two graphs show what happened from 3:40 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. on July 11, 2021. Between 4:05 p.m. and 4:20 p.m. there was a 100% drop in traffic to and from Cuba, according to the network traffic monitoring companies Kentik and IODA.

IODA measured the same drop using BGP and Active Probing metrics. These metrics are consistent with intentional disruptions of social media and certain services, which shows that the outages targeted specific platforms or selected geographic areas, rather than imposing a total traffic blackout.

What Will the Internet Be Like After July 11?

Moving back and forth between digital and physical environments is a revolutionary transformation that is just beginning in Cuba and will expand in the future.

In terms of immediate consequences, July 11 has revealed that citizens through their actions are agents of change. People action is social regulation of political power, moving from what could be be a rough confrontation into a dialogue reflecting the real interests of individuals. The government response could be to simply disconnect the network at the slightest murmur of discontent. But it turns out that efforts to disconnect or limit network access only fuel the need to stay connected.

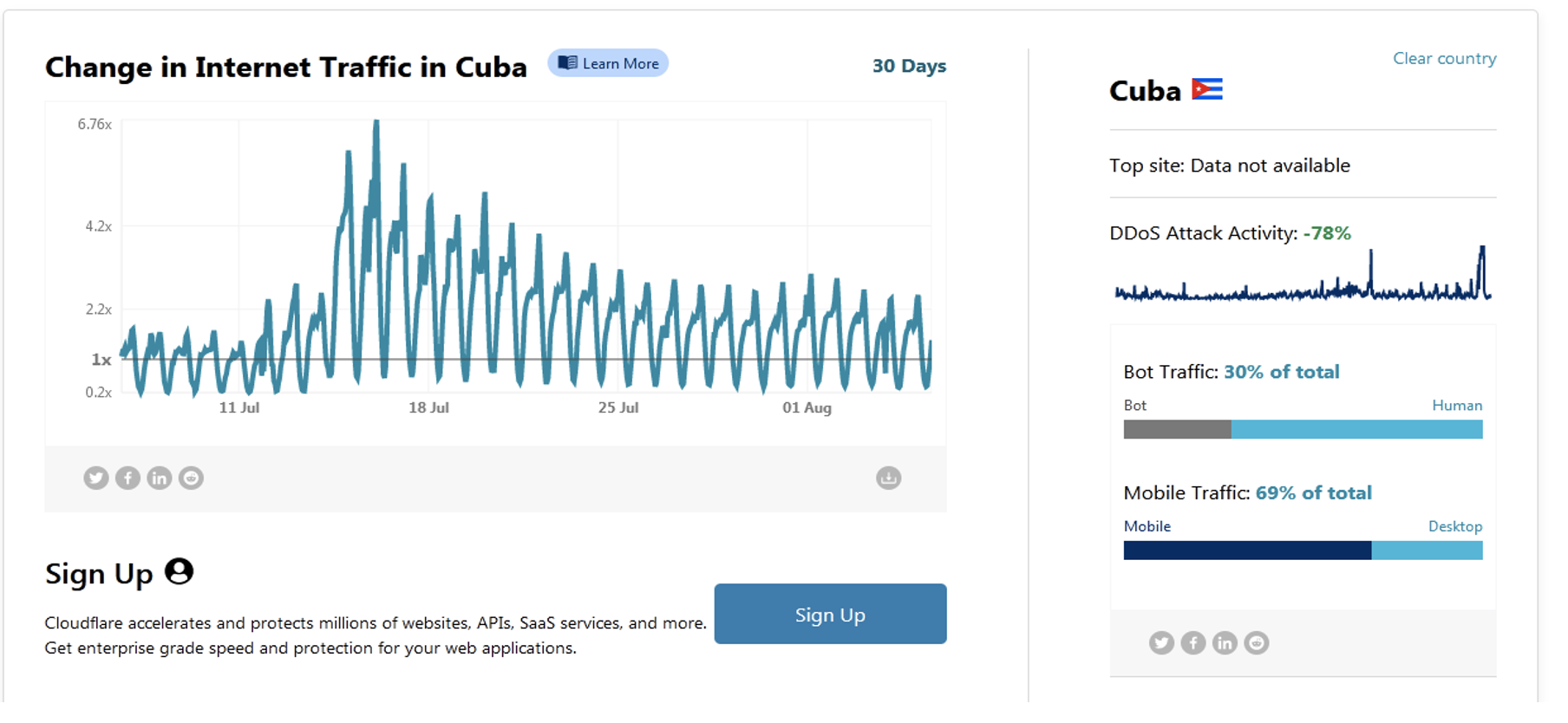

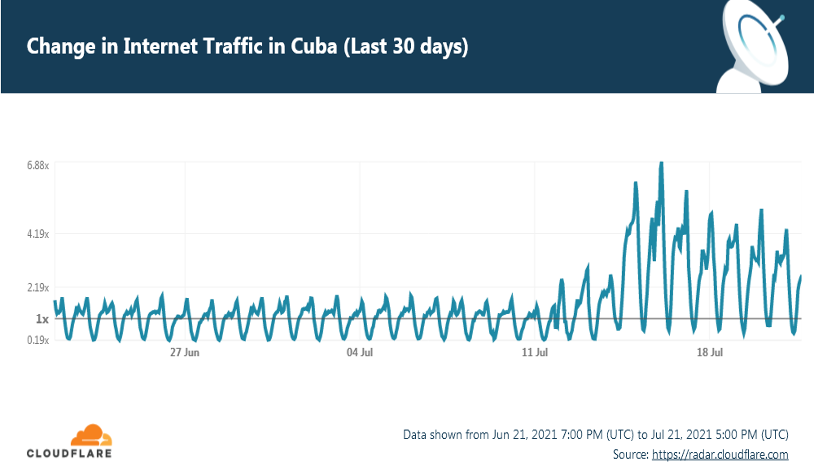

Despite Internet service disruptions, there was a three-fold increase in traffic during the protests and the week afterward. As seen in the metrics and reports from Cloudfare and kentic:

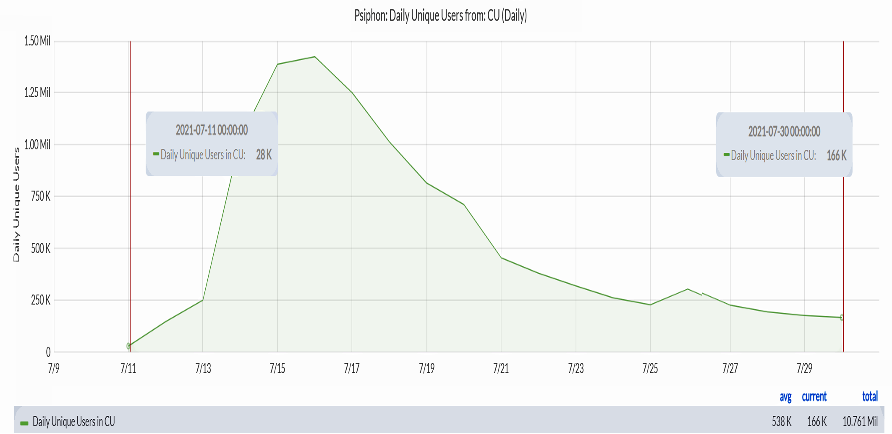

The increase in traffic occurred through the use of VPNs, widely used in Cuba before, during, but mainly after the demonstrations. The VPN platform Psiphon stated that the number of individual users connecting from Cuba reached a record of 1,000,389 on July 15. Before the protests, Psiphon’s daily VPN users numbered about 28,000 per day. Now it seems to hold steady at around 166,000 daily users.

As of July 11, the outages occurred sporadically, which suggests that they are in specific geographic areas or on selected mobile networks and platforms. NetBlocks network data confirmed the partial disruption of social media and messaging platforms as of 4:05 pm on July 11, 2021.

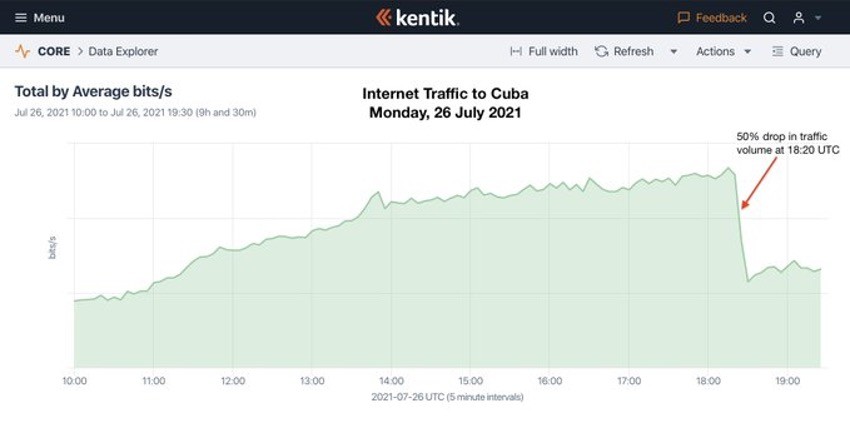

The service outages have continued with greater or lesser intensity. For example, this graph points to a drop of more than 50% for over two hours on Monday, July 26.

According to NetBlocks, the most affected services were WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and some Telegram servers. Access to the YouTube streaming platform and Google Video servers was also limited for days. Twitter was not affected; its penetration in Cuba is not significant compared to Facebook. Based on NetBlocks’ Internet performance metrics, fluctuations affected between 90% and 52% of operations, especially in services related to CDM Content, Web Interface and CDN Video, which are used to upload and share live videos.

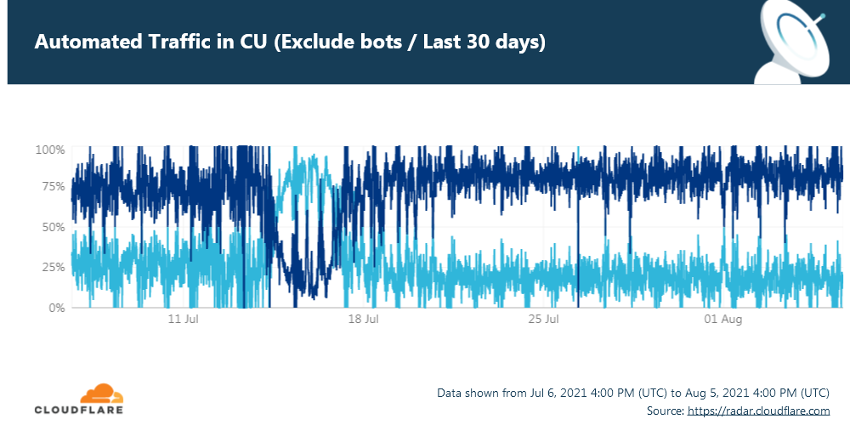

Another change in local Internet dynamics attributed to July 11 was the drop in the percentage of human traffic compared to traffic of bots or spam. Some of this change may be due to blocking human traffic, but it is also due to increased search engine activity.

Several Cuban authorities attributed the increase in the percentage of automated traffic to the United States government. But an independent group’s analysis does not support that claim. From a sample of 1,048,576 tweets with the hashtag #SOSCuba published between July 10 and 12, 2021, the study concluded that “the contribution of bots and spam was negligible compared to the actual organic tweets of Cuban citizens on the island and supporters (human rights defenders, journalists, bloggers and artists) from other nations. The vast majority of the photos and videos posted on Twitter were authentic. Ninety-three ‘highly suspicious’ accounts posted more than 144 tweets per day and generated 27,442 tweets, but that was only 2.66% of the total.”

The increase in bots is likely due to the fact that, unable to access the usual platforms, users combed search engines for information about what was really happening.

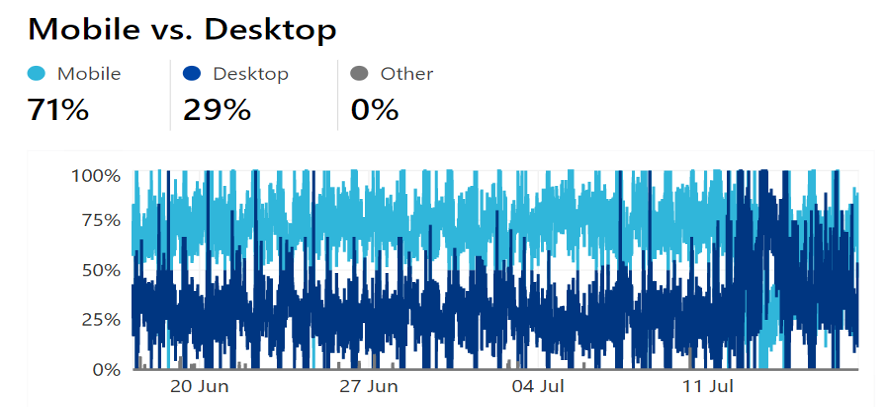

Another interesting piece of information is that traffic was abruptly truncated from mobile networks to fixed networks, as shown below. This shows that the outage was made on the mobile data network, while other networks were working normally.

Drops in traffic have become common on the island, whether due to technical problems or deliberately (it can be difficult to distinguish between them, technically speaking). The following graph from June 28 to July 25 using BGP metrics has quantified at least three significant outages between June 30 and July 5 and 11.

Mass Self-Communication Is Shaping Another Reality

Gilles Deleuze used the term “rhizome” to describe this new system (network) that evolves in unexpected ways to multiply and thus encourage and promote its self-communication through unexpected paths. Its participants no longer follow lines of hierarchical subordination: anyone can affect or influence anyone. The social outpouring on July 11 presupposes a radical paradigm shift that has forced almost all public authorities to understand that the delegation of sovereignty cannot be exercised independently from interacting with citizens. Not only in terms of discourse and/or traditional communication, but also with the speed and agility of digital platforms.

Disconnecting a network is an apparently simple act, but as we have seen, in the arena of post-July 11 technopolitics, citizens know how to connect, even when they have been disconnected. They already inhabit this new hybrid space that allows them to reproduce democratic structures from the digital to the physical.

Gutiérrez-Rubí explains that digital citizens are no longer “passive, patient and silent” and instead have become “active, speaking and demanding social agents.” So let us hope that a new path is forged where we deliberate and consider social relations, institutions, power, social change, and personal autonomy as realities based on horizontal and not vertical networks.

The young people who mobilized during the 2019 tornado are part of our first digital generation, and they put the principles of technosociability into practice. A culture that not only changes the lives of individuals and communities, but also political and symbolic relationships.

The current United States administration and the Senate approved an amendment that asks President Biden to facilitate free Internet access in Cuba by creating a fund that enables this “open and uncensored” service. During his election campaign, Biden promised to return to the thaw with Cuba and reverse many of the sanctions imposed by former President Donald Trump, but his views seem to have changed since he arrived in the White House.

Among the provisions that “support Internet freedom in Cuba,” the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) encourages companies and individuals to take advantage of exemptions and authorizations to provide software and services to Cuban Internet users in the area of telecommunications and the establishment of Internet providers, among other steps.

The Department of the Treasury authorizes commercial activities that cover the provision of certain paid Internet services, communication services such as email or other messaging platforms, social networks, web hosting and domain name registration, etc. Another area of commercial activities extends to granting licenses for software design, business consulting, management, and information technology support.

For its part, the Cuban Assets Control Regulation (CACR) now authorizes some transactions related to the establishment of facilities to provide telecommunications services linking the United States or third countries with Cuba. Among them the CACR includes connectivity to the Internet, data, telephone, telegraph, radio, television, and cable news, regardless of the medium of transmission, including satellite transmission.

Finally, they include a series of activities aimed at online learning and educational training, and travel-related transactions that directly affect the export, import, or transmission of these materials are made more flexible.

Access to a free Internet outside the control of local authorities, beyond the implications of political rhetoric and the dispute between Cuba and the United States, has little technical credibility. To establish access to telecommunication services in Cuba, not only is authorization needed, but above all the collaboration, from local regulatory bodies and also from international bodies. Without them it is impossible to deploy any communications infrastructure, even global, such as Starlink or Intelsat.

The Cuban government has responded through a high-level regulation, Decree Law No. 35, which not only updates the governance of radioelectric space, but also establishes a series of violations that include new offenses, such as the “danger of perpetuating fake news” (“eco mediático de noticias falsas”).

It is likely that as the events of July 11 are considered, the result will not be beneficial for the short-term future of the Internet in Cuba, much less for its new users and for their aspirations to be heard. The opposite is likely to be true. Nonetheless, networks—whether individual or community—should be further deployed through inclusive policies (lower prices and improved connectivity by ETECSA) to facilitate an open and inclusive debate, and not internal political or ideological extremism, which reinforces confrontation in international relations.

The causes of July 11 go beyond the usual bipolarity of extremes in contemporary Cuban history. The causes, factors, and consequences of the peaceful and violent mobilizations of the July 11 protests may be both local and universal. They result from the fact that the management of the pandemic and the economic collapse make it clear that traditional political discourse, as well as the superstructures and institutions of the failed economic models that sustain them, have lost their control over social intermediation.

Note

Manuel Castells: Redes de indignación y esperanza: los movimientos sociales en la era de Internet, Alianza Editorial, Madrid, 2012.