Cuba: The Polycrisis and the Political Power that Inverts the Relationship between Politics and Economics

Juan Carlos Albizu-Campos Espiñeira

Centro Cristiano de Reflexión y Diálogo (CCRD-C)

The current Cuban economic model, as it is conceived, applied and operated, cannot be reformed. Cuba needs to adopt a new model and reintegrate into international financial institutions because it cannot continue isolated from the rest of the world.

A National Crisis with a Growing, Endogenous Poverty

Our economic crisis is systemic and has a structural character [1]. It is result both of a model of society founded on the centralized exercise of power, which inverts the relationship between politics and economy, as well as on the economic contractions that the embargo/blockade has been generating since 1960. According to Torres and Echevarría (Torres P. & Echevarría L., 2021, p. 1), Cuba has undergone “a historical pattern of recurrent economic crises derived from negative external shocks combined with internal errors”.

Contrary to the Marxist assertion that “politics is the concentrated expression of the economic interests of the ruling class,” the Cuban model instead reflects that all dimensions of society, including its very conception, and its economy, depend on the political vision of the country’s top leadership, based on an exclusive single political party.

Since very early in the second half of the 20th century and until now, the country has had to go through various acute phases of economic crisis. Without limitation, they may be listed as follows:

- Crisis of the Budgetary Financing model, together with the Self-management model and the Economic Registration System (1966-1974). [2]

- Crisis of stagnation of the economic calculation model (“errors’ rectification” period, 1985-1990).

- Crisis of the so-called “Special Period in Times of Peace” (1991-1995).

- Crisis of disintegration of the sugar sector, which began in 2002, and dismantling of the agro-industrial complex.

- Recentralization crisis and the economic slowdown that began in 2006, decapitalization of infrastructure and equipment, and subsequent recession: the economic model as an obstacle to development (Pérez-Villanueva & Torrez Pérez, 2013).

- Collapse of the real estate bubble and the international financial crisis. 2007-2009.

- Contraction of tourism and remittances. National financial crisis.

- Sustainability crisis of the Cuban Economic Model. 2013-2019.

- Combined pandemic crisis --country closure. “Economic Regulation”. Since 2020.

The summary above does nothing other than show that the current economic model, as it is conceived, applied and operated, cannot be reformed. All these crises reveal that the Cuban economic model is really a progression of crises, with more or less acute phases from time to time. At times, the economic malfunction has been concealed by strong external financing and subsidies. Whenever the flow of foreign funds has been interrupted, however, the economic crisis manifests itself with greater force, as the conditions affecting productivity and the need for capital investment remain unchanged.

Just over half of the Cuban population contributes to economic activity (only 4.8 million employed out of the little more than 7.6 million inhabitants of working age, who are able and qualified to work). Moreover, this low labor force participation rate is combined with a profound structural deformation in government spending. Governmental investments continue to favor the real estate sector and tourism, totaling 46% of all investment in 2021, as compared to governmental investment in the following:

- 0.8% in health and social assistance;

- 5.9% in the agricultural sector, in a country with notable food insecurity (which sum, in 2022, was reduced to less than 3%);

- 0.6% in science and technological innovation;

- 0.6% in education;

- 2.9% in construction, which fell to 1.7% in 2022; and

- 9.4% in the supply of electricity, gas and water, which was reduced to 6.6% also in 2022.

This spending distortion is the result of an economic model conceived without space for the participation of all possible national and international economic actors, as compared to a model of profound economic liberalization in which all actors participate. The Cuban economic model has also resulted in “push and pull” measures, reforms and counter-reforms of which micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (in Spanish micro, pequeñas y medianas empresas, ‘Mipymes”) have been the main victims.

Mired in fear and ideologically clinging to an orthodox and exclusive vision, the authorities do not perceive the need for a real and effective reform.

Thus, crisis shortages of all kinds follow one after another: fuel, energy, decapitalization of the manufacturing industry (only 12.8% of investment in 2021, the lowest in the Latin American region) and the sugar industry, which went from 2.0% to 0.4% in that biennium. All of this has been accompanied by an inability to recover from a variety of phenomena that have smacked the country, from natural disasters to devastating accidents, from plane crashes to the destruction of a base of super fuel tankers.

Mired in fear and ideologically clinging to an orthodox and exclusive vision, the authorities (supposed representatives of the working class) do not perceive the need for a real and effective reform that allows a true liberation of the productive forces and the consequent economic transformation of the country. Faced with the possibility of leading the country towards a model of prosperity, which would also require addressing and solving the inequalities generated during the last six decades, they have elected to choose what they call "continuity" of the current model of "equity in misery" (equality in pauperity, José Martí would say).

The results are obvious:

- A currency depreciation of 95.83% (Cifuentes, 2022) (Bloomberg Línea, 2021).

- The lowest per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the Western Hemisphere (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021, p. 15).

- The highest annual index of misery globally (Hanke, 2022), driven by a record inflation that reached levels between 740% (Hanke, 2022), 1,221% (Hanke, 2022) and 1,840% (Peña Castellanos, 2022).

Meanwhile, in a perverse application of Hirschman's “Exit, Voice and Loyalty” model (Hirschman, 1994), they gain time by “promoting” the mass exodus of the population. Recent figures have estimated it at 3.5% in 2021 alone - the main migration crisis in the history of Cuba.

Thus, as Mesa-Lago says, “it is not feasible to get out of the crisis with the current policies.” And both “China and Vietnam demonstrate the failure of the Cuban socioeconomic model” (Mesa-Lago, 2002). De Miranda would say: “The situation of the Cuban economy is such that it requires a kind of Marshall Plan to overcome its prostration” (Betancourt-Ponce de León, De Miranda-Parrondo, Mesa-Lago, & Amor-Bravo, 2022).

The country lacks internal sources of capital accumulation to face economic development and no longer has a special foreign ally that transfers resources for political considerations. In fact, the current political-economic model itself is the main obstacle to a way out of the current crisis and the further development of the country, since the brakes that prevent progress are produced and reproduced there.

Towards an Economic Model Oriented to Human Development and Welfare integrated into International Financial Institutions

The model we need would have to be endogenous, sustainable and comprehensive. It should aim for a profound paradigm shift of the system that may well be oriented towards a mixed model, such as the Scandinavian countries or Vietnam. In any case, it has to be a model oriented towards human development. According to the reports of the Human Development Index 2007, 2017 and 2021-2022 (UNDP, 2009) (UNDP, 2018) (UNDP, 2023), Cuba fell 32 places in the international ranking of the human development index, going from 51st place in 2007 to 73 in 2017 and falling to 83 in the 2021-2022 biennium. This drop has no equivalent on a global level.

Recovery in this sense and future progress could only be possible from models such as the “circular economy”. Coupled with significant resources from an international aid package, we could expect that the country's economy could begin to overcome the state of prostration to which it has been brought by obstinate authorities who have refused to change economic model and instead dedicate themselves to implementing “patch” type solutions - as if we were facing a temporary emergency.

We would have to start by recognizing the problem presented by the lack of convertibility of the Cuban peso. Without addressing that, everything else we do will be minimal and continue to prolong an unsustainable situation. We have explored this issue ad nauseam. The difficulty lies in the fact that the Cuban economic model does not generate sufficient resources so that there is insufficient accumulation of capital internally. In my view, this obstacle is insurmountable under the current system.

One plausible solution, not without difficulties, would be to replace the Cuban peso (CUP) with any other currency that appears available and that Cuba is allowed to use, even if the currency’s country does not belong to any international commercial zone. As to dollarization, there are several examples we can look to in the region: Panama, El Salvador and Ecuador. Further away, we have Andorra, Vatican City, Monaco and San Marino, all of whom use the Euro and mint their own currencies under agreements signed with the European Union. Moreover, Montenegro and Kosovo, without entering into any legal agreement with the European Union, use the Euro, as does North Macedonia, just to mention a few examples.

Meanwhile, Cuba's own disconnection from international financial institutions, among other things, due to the United States embargo/blockade, currently makes external financing that would be essential virtually impossible.

The main multilateral development banks are (MDBs):

- The World Bank.

- The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD).

- The European Investment Bank (EIB).

- The Islamic Development Bank (IsDB).

- The Asian Development Bank (ADB).

- The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

- The CAF-Development Bank of Latin America (CAF).

- The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) Group.

- The African Development Bank (AFDB).

- The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

The central banks or monetary unions or associations of central banks:

- The Central Bank of West African States.

- The Bank of Central African States.

- The Eastern Caribbean Central Bank.

- The European Central Bank (ECB).

The Monetary unions, formal or informal, but without an international central bank:

- The African Association of Central Banks.

- The Southeast Asian Center for Central Banks (SEACEN).

Other international financial institutions of note:

- The Bank of International Settlements.

- The Financial Stability Council.

- The Latin American Reserve Fund.

- The Arab Monetary Fund.

- The International Monetary Fund.

As part of a development plan, Cuba would have to reintegrate into the set of international financial institutions because it cannot continue isolated from multilateral and regional financial mechanisms. Among them and, in particular, are the following: the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank (WB), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the CAF-Development Bank of Latin America (CAF), the Inter-American Development Bank Group (IDB), the Bank for International Settlements, the Financial Stability Council and the Latin American Reserve Fund.

Industry, Agriculture, Infrastructure, Transportation, Communications, National or Foreign Investment

An essential component of a development plan will be to redefine the law for foreign investment. It is not possible to allow, under any circumstances, a law that only offers investment opportunities to foreigners to the exclusion of Cuban citizens.

As many Cubans will remember, this was called disparagingly as “servilism”, “surrendering”, with all the ideological burden of those times. Cuba must adopt a common legal body of laws and procedures for all potential investors, whether foreign or national, in which the investment process is regulated.

Furthermore, the “portfolio of opportunities” for investment must be set aside. By identifying it an exclusive list, it limits the interested investor to the sectors, branches and activities of interest to the State. This fails to take into account that, being the owners of the funds to be invested, their investment goals do not necessarily coincide with those of the State. Investment in areas not prioritized by the State, are thus wasted by the State.

A fundamental problem is that Cuba is completely outside of and isolated from global value creation chains. Only through solid integration into these global chains will it really be possible to generate economic development and national wealth. And this would not only guarantee access to significant volumes of foreign direct investment and global supply chains, but also create a sustained export of goods and services.

Continuing to insist on a system of autarky is not only archaic, but constitutes the primary obstacle to accessing financial resources, modernizing technology and diversifying logistics that the country demands.

We urgently need a legal framework to replace the current one regulating economic matters...focused on the protection of property and compliance with the contractual conditions.

Another early key step would be taking advantage of the new integration opportunities based on what is known today as “nearshoring” and which have operated successfully worldwide. These arrangements allow the host country access to new technologies, know-how, capital flows, supply chains, export chains and integration into unified regions with meta markets.

Development is not Possible in a Context of Legal and Institutional Fragility

None of the above will be possible without a solid legal restructuring that becomes a true support for a profound process of economic liberalization. There will be no foreign investment if Cuba continues to be classified as a “high risk” country for investment.

We urgently need a legal framework to replace the current one regulating economic matters. It must be focused, first of all, on the protection of property and compliance with the contractual conditions, on which all economic and commercial activity is based, both nationally and internationally. Secondly, it must engage the country in international practices, and the State must comply with its obligations, beginning with the repayment of loans both private and public.

From Equality in Misery to a Model of Prosperity that Addresses the Solution to Inequality

The Cuban economic crisis is systemic and has a structural character. Its origin is fundamentally endogenous, although it has certainly been aggravated by the impact of various international factors, notably measures of the U.S. embargo, which have had at times particularly negative impacts.

However, the internal management of the economic model has been particularly perverse. There is a tendency to identify the crisis, or the acute phases of the crisis, with the disappearance of the socialist camp and of the Soviet Union and the generous subsidies the latter granted to Cuba.

What really happened is that the system entered into crisis very early in the Revolution when the so-called “Budget Financing” model was applied (1966-1974), eliminating any role in the economy for monetary-mercantile relations. The corporation was eliminated as a production unit along with its independent legal status. The central authorities arbitrarily assigned the inputs and outputs of the enterprise, as opposed to permitting the business itself to buy inputs and sell products in a commercial market, responding to market needs. As a result, the central authorities came to control the enterprise operations; the enterprises were not able to manage their assets; the whole work force was turned into hourly workers; and the enterprises could not provide material incentives to their employees in order to stimulate productivity.

These measures were combined both with a virtual elimination of private property as an economic actor and an aggressive intervention-expropriation program, implemented towards the end of the 1960s.

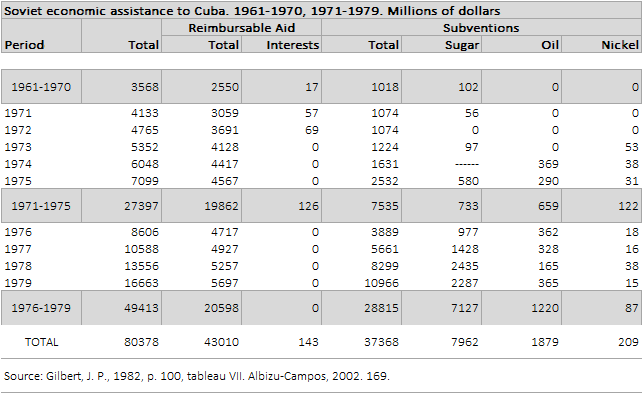

Although official statistics are not available, the measures described above naturally led to a significant contraction of the economy. Its acute phase covered most of the period 1966-1974 and ended after a change in the conceptualization of the economic model implemented after the First Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) in 1975 and the influx of strong financing from abroad, in particular from the Soviet Union. In just the two decades of the 1960s and 1970s Soviet bloc financing approached 80,378 million dollars (Gilbert, 1982, page 110) (Albizu-Campos E., 2002, page 169) for a population that, on average, only reached 8.2 million inhabitants during the period. According to Díaz-Briquets, Cuba had received an endowment of resources that would exceed the aggregate per capita income provided by the Marshall Plan and the Alliance for Progress.

Devereaux (2021) even suggests that the total amount of transfers from the Soviet bloc to Cuba may have been higher: $63 billion in nominal terms and around $115 billion at 1990 prices.

Despite the massive financial influx, Cuban economic performance has been astonishingly negative and, consequently, the results have been remarkably adverse. Productivity per worker is lower today than in 1958. Moreover, Cuba generated the worst economic performance of the world economy after 1958, excluding marginal cases such as North Korea. Since then growth has been “glacially” slow, while GDP per capita increased a mere 40% between 1957 and 2017, equivalent to an annual growth rate of 0.6%, one of the lowest in the world (Devereaux, 2021).

With the external funding and additional foreign funding received in the 1980s mainly from USSR, as well as the implementation of a new form of organization and planning of the economy known as “Economic Calculation”, as well as Cuba’s integration into the Mutual Aid Council Economic (CAME), the economy managed a revival and achieved stable economic growth until at least 1985. Then, a slow, although sustained, contraction of GDP occurred following the process called "rectification of errors", although the contraction was in part concealed by funding from external sources.

Upon Cuba’s loss of fundamental economic-commercial relations due to the disappearance of the Soviet bloc, particularly the Soviet Union, an acute phase of economic crisis referred to by the government as the “Special Period in the Time of Peace” began. An entire decade (1985-1995) of structural breakdown was set in motion, building upon the existing distortions generated in the previous crisis (1968-1974).

Cuba must move from its current model of “equality in misery” towards a model of economic development and prosperity, addressing inequality by creating a safety net that guarantees the survival of vulnerable groups and those living in even worse conditions.

To solve the current problems suffered by the population and create a viable economy will require massive investment, effort and time, no doubt. A first step would be an official governmental acknowledgement that the country is facing an existential crisis that demands dedication from all, internally, and externally, including aid agencies and international funds and funds for humanitarian relief.

The Cuban social science academy has repeatedly offered a detailed picture of the entire inventory of problems facing the country, which have been analyzed and documented during the last decades, the existence of many of which the governing authorities have not even acknowledged. Instead, they still insist on “reforming” or “getting off the ground” an economic model that is the main impediment to development (Pérez Villanueva, 2010). The authorities focus on temporary and limited solutions - reinforcing the cascade of overlapping and interconnected crises that have done nothing more than "aggravate the magnitude of the pending challenges". The result is the dramatic and long lasting polycrisis which has seriously and definitively undermined the "metabolism" of the system, as happened in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in the 1990s, when their societies imploded (Díaz -Briquets & Albizu-Campos E., 2024) (Tooze, 2022) (Hobson, 2022) (Lawrence, Janzwood, & Homer-Dixon, 2022) (Lawrence, et al., 2023).

References

Albizu-Campos E., J. C. (2002). Mortalité et survie à Cuba dans les année mille neuf cents quatre-vingt-dix. Lille, Nord-Pas-de-Calais, France: Atelier National de Reproduction de Thèses. Université de Lille 3 - Charles de Gaulle.

Betancourt-Ponce de León, O., De Miranda-Parrondo, M., Mesa-Lago, C., & Amor-Bravo, E. (14 de Febrero de 2022). La economía cubana necesita de un “Plan Marshall” para superar su postración (Dossier).

Bloomberg Línea. (2021 de Enero de 2021). Las 15 monedas más depreciadas del mundo. (Bloomberg Línea)

Cifuentes, V. (06 de Enero de 2022). Peso colombiano: ¿Qué lugar ocupa entre las monedas más depreciadas del mundo?

Devereaux, J. (31 de March de 2021). The absolution of history: Cuban living standards after 60 years of revolutionary rule. (A. G. Galvarriato, M. A. Pons, & H. Willebald, Edits.) Revista de Historia Económica-Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History, 39(1), 5-36. doi:10.1017/S0212610920000233

Díaz-Briquets, S., & Albizu-Campos E., J. C. (1 de January de 2024). Systemic Failure and Demographic Outcomes: Cuba’s Perfect Storm. (J. Duany, Ed.)

Economist Intelligence Unit. (2021). Cuba. Country Report. 1st Quarter 2022. The Economist Intelligence Unit.

Gilbert, J. (1982). Les échanges économiques entre Cuba et l'Union Soviétique. Problèmes d'Amérique Latine(64), 93-121.

Hanke, S. (16 de March de 2022). Hanke’s 2021 Misery Index: Who’s Miserable and Who’s Happy?

Hanke, S. (24 de 11 de 2022). Hanke's Inflation Dashboard (11/24/2022).

Hirschman, A. (1994). Salida, voz y el destino de la RDA. Un ensayo de historia conceptual. Claves de Razón Práctica, 1994(39), 66-80.

Hobson, C. (18 de August de 2022). Polycrisis in this valley of dying stars. Obtenido de Polycrisis in this valley of dying stars-Imperfect notes on an imperfect world.

Lawrence, M., Homer-Dixon, T., Janzwood, S., Rockström, J., Renn, O., & Donges, J. F. (1 de June de 2023). Global polycrisis: The causal mechanisms of crisis entanglement. Version 1.0.

Lawrence, M., Janzwood, S., & Homer-Dixon, T. (1 de September de 2022). What Is a Global Polycrisis? Version 2.0. Obtenido de What Is a Global Polycrisis? Version 2.0-The Cascade Institute.

Mesa-Lago, C. (2002). Buscando un modelo económico en América Latina. ¿Mercado, socialista o mixto? Chile, Cuba y Costa Rica. Caracas, Venezuela: Editorial Nueva Sociedad.

Peña Castellanos, L. (2022). Inflación, el reordenamiento y el pronóstico de crecimiento de la economía cubana para el año 2022: una mirada desde la problemática de la inserción internacional de la economía cubana. Revista Cubana de Economía Internacional, 9(1), 158-172.

Pérez Villanueva, O. E. (2010). Estrategia económica: medio siglo de socialismo. En O. E. Pérez Villanueva, Cincuenta años de la economía cubana (págs. 1-24). La Habana, La Habana, Cuba: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

Pérez-Villanueva, O. E., & Torrez Pérez, R. (. (2013). Economía cubana. Ensayos para una restructuración necesaria (Única ed.). (M. T. S.A., Ed.) La Habana, La Habana, Cuba: Centro de Estudios de la Economía Cubana; El Foro Mundial; UNDP.

PNUD. (2009). Informe de Desarrollo Humano 2009. Superando barreras: Movilidad y desarrollo humanos. New York: Grupo Mundi-Prensa: (G. Ink, Ed., & C. LTS Mundo y Tilt Diseño, Trad.

Tooze, A. (28 de october de 2022). Welcome to the world of polycrisis.

Torres P., R., & Echevarría L., D. (2021). Nota introductoria. En R. Torres P., D. Echevarría L., e. al., D. Roque, & G. Pérez (Edits.), Miradas a la economía cubana. Elementos claves para la sostenibilidad (IX ed., págs. 1-4). La Habana, La Habana, Cuba: Ruth Casa Editorial.

UNDP. (2018). Human development indices and indicators 2018. Statistical updates. New York, New York, USA: Communications Development Incorporated.

UNDP. (2023). Human development report 2021/2022. Uncertain times, unsettled lives: Shaping our future in a transforming world. New York, New York, USA: RR Donnelley Company.

[1] Responses from Juan Carlos Albizu-Campos to the Cuba Próxima dossier “Cuba Needs to Replace the Current Impoverishing Economic Model”, in which Mauricio De Miranda Parrondo, Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva, Pavel Vidal Alejandro and Tamarys Lien Bahamonde Pérez also participate

[2] Blanco, L., 2024, Personal comments to the author.

Juan Carlos Albizu-Campos Espiñeira holds a degree in Industrial Economics from the University of Havana (1986) and a specialty in Demography from the Latin American Demography Center, Costa Rica (1989). He obtained a Ph.D. in Economics at the University of Havana (2001) and a Ph.D. in Demography, University of Paris X-Nanterre (2002). He served as professor at the Center for the Study of the Cuban Economy (CEEC), University of Havana.

He has published, among other works, Dinámica demográfica cubana. Antecedentes para un análisis; "Fertility, GDP and Average Real Wage in Cuba"; La migración internacional de cubanos; "Current Scenarios: Cuba"; "Escenarios demográficos hacia 2030"; Hacia una política de población orientada al desarrollo humano; "Cuba: A look at the Economically Active Population"; "Cuba. Aging and Demographic Bonus"; "Challenges to Development"; "Is the Decline in Economic Activity of the Population a Temporary Phenomenon in Cuba"; ¿Zozobra Demografica?; "The Ghost that Haunts Cuba"; "Life Expectancy in Cuba Today: Differentials and Conjunctures"; "Maternal mortality in Cuba: Color counts".

He has obtained several National Awards from the Academy of Sciences of Cuba and the University of Havana.