Coping with Systemic Problems and a Triple Punch: The Cuban Economy at the Start of 2021

At the start of 2021, the Cuban economy finds itself in very precarious conditions.

By Paolo Spadoni

Associate Professor Political Science, Augusta University

With export operations no longer concentrated on sales of primary goods, today’s Cuban economy is basically a service-based economy in which exports of professional services and, to a lower extent, international tourism (along with overseas remittances) have become the country’s main sources of hard currency. At the start of 2021, the Cuban economy finds itself in very precarious conditions. Above all, Cuba continues to suffer from all the inefficiencies, red tape, and distortions of its state-dominated and overly centralized economy. In need of deep structural changes, the island’s socialist system can serve neither as an effective tool to unleash productive forces nor as a model to foster actual development. Moreover, Cuba’s external environment has deteriorated markedly due to the economic (and political) crisis in Venezuela and because of President Donald Trump’s efforts to roll back the U.S. policy of engagement toward Havana initiated by Barack Obama. Needless to say, the adverse economic consequences of the new coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic have added another major problem.

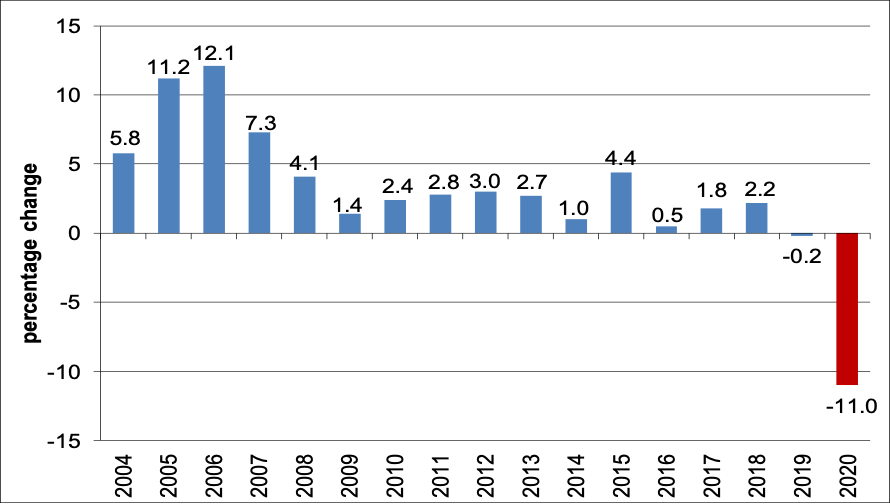

Figure 1. Cuba's GDP Growth, 2004-2020a

Sources: ONEI 2020, 2019, 2013, 2007; MEP 2020.

Note: a. Estimate for 2020.

Economic Conditions

Figure 1 reports data on Cuba’s annual GDP growth rates at constant 1997 prices between 2004 and 2020. Fueled in particular by thriving exports of medical and other professional services under a comprehensive deal with Venezuela (involving large supplies of Venezuelan oil to Cuba) and, to a lesser degree, sizable revenues from nickel exports and international tourism activities, Cuba’s GDP grew 11.2% in 2005, 12.1% in 2006, and 7.3% in 2007. After 2007, nonetheless, the Cuban economy witnessed a steep deceleration. Cuba’s annual GDP averaged 2.7% in 2008-2013 and only 1.6% in 2014-2019. Albeit small, the GDP contraction (-0.2%) in 2019 was the first such decline since 1993. Primarily due to the negative effects of the coronavirus global pandemic, Cuba’s GDP is estimated to have shrunk by around 11% in 2020, which is noticeably worse than the average result (-7.7%) in Latin America and the Caribbean (MEP 2020; CEPAL 2020).

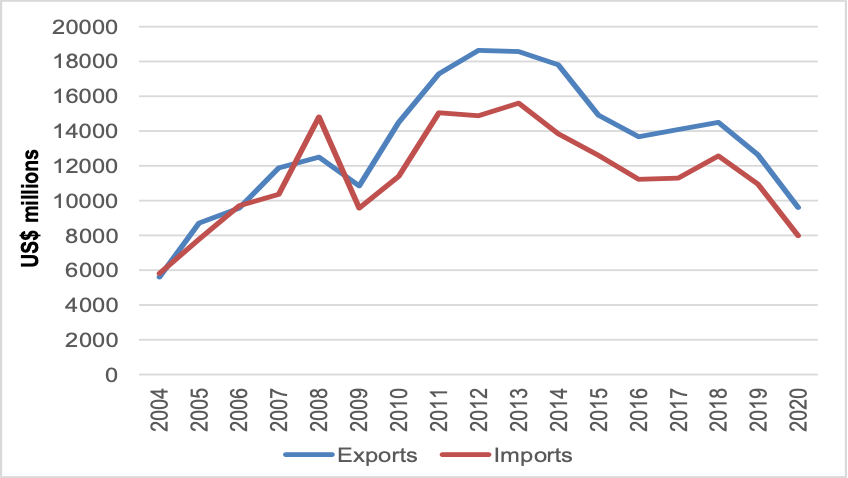

Figure 2. Exports and Imports of Goods and Services, 2004-2020a

Sources: ONEI 2020; 2019, 2013, 2007; MEP 2020.

Note a: Estimates for 2020.

Figure 2 highlights the evolution of Cuba’s external trade (annual values of exports and imports of goods and services) between 2004 and 2020. The Cuban economy has always been an open economy with strong dependence on external sector activities, particularly on those involving foreign trade. Cuba’s annual trade balance in goods and services regularly ran deficits between 1990 and 2004 as rapidly expanding tourism revenues failed to offset a rising merchandise trade deficit. It was only after 2004, when exports of professional services rose steeply, that the overall trade balance began to post surpluses, though not every year. Exports of goods and services jumped from $5.6 billion in 2004 to $18.6 billion in 2013, but they have decreased considerably since then to $12.6 billion in 2019. They dropped further in 2020, possibly to less than $10 billion, as tourism income plummeted dramatically and hard currency earnings from other major sources declined as well. Cuba’s overall trade balance might have recorded a surplus in 2020 only because imports were cut by around 30%[1]. In any case, Cuba keeps relying on large amounts of imports (primarily fuels, foodstuffs, machinery and equipment, and manufactured goods) to supplement insufficient domestic production and alleviate the needs of its society. Besides the disappointing results of the island’s excessively centralized agricultural sector, it is worth noting that the industrial output of the Cuban manufacturing industry in 2019 was only 70% of its level of 1989 (ONEI 2020). Cuba also faces several problems that limit the adequate functioning of the external sector. These include a large merchandise trade deficit, excessive trade concentration in terms of both products and markets, vulnerability to external trade shocks (particularly to international price swings), and overreliance on export activities with low cross-sector spillover effects.

Yet, since the end of 2019, as cash shortages intensified due to toughened U.S. sanctions as well as declining foreign exchange earnings and international reserves, Cuba has once again struggled to pay its debt to overseas companies and creditor countries.

A sizable external debt in hard currency, a liquidity crunch, and other mounting financial troubles exacerbated by a worsening external environment have placed additional burdens on Cuba’s struggling economy. Cuba’s total debt increased from $11.6 billion in 2008 to $18.2 billion in 2016 (but dropped slightly to $17.8 billion in 2017, the last time it was reported) even if the country was able to obtain substantial debt relief in the meantime. Major write-offs of Cuban debt included $6 billion by China in 2011, some $1.4 billion by Japanese commercial creditors in 2012, and nearly $500 million by Mexico in 2013. More recently, in 2014, Russia cancelled 90% of Cuba’s $35.2 billion debt to the Soviet Union while an agreement with the Paris Club in 2015 forgave $8.5 billion of Cuba’s $11.1 billion defaulted debt and restructured payments on the remainder. Yet, since the end of 2019, as cash shortages intensified due to toughened U.S. sanctions as well as declining foreign exchange earnings and international reserves, Cuba has once again struggled to pay its debt to overseas companies and creditor countries.[2] Furthermore, and critically important, Cuba suffers from inadequate levels of foreign investment and major systemic flaws that stifle economic growth and development.

Systemic Problems

The Cuban economy indeed suffers primarily from severe structural problems. Among them are:

- a weak capacity to generate domestic savings to support investment;

- low productivity levels of most state-run companies;

- relative price distortions stemming from government controls that hamper market mechanisms;

- and until January 1 of this year, a dual currency system with multiple exchange rates that created strongly segmented spheres of economic activity, diminished linkages between enterprises, and discouraged foreign investment.

Insufficient gross capital formation, which refers to domestic investment in factories, machinery, tools, equipment, and other productive capital goods, is a major debilitating factor for the Cuban economy. The ratio of gross capital formation to GDP, remarkably, was 25.6% in 1989, but since then it has never surpassed 15% and actually averaged only 10.4% between 2000 and 2019. Annual results similar to that of 1989 are required to reverse the decapitalization of key sectors and spur adequate rates of economic growth (Pérez Villanueva 2017). Hoping to boost its economy, Cuba has stepped up efforts to attract badly needed foreign investment after the opening in late 2013 of the Mariel Special Development Zone and the enactment of a new foreign investment legislation (Law 118) in June 2014. Cuba is seeking $2 billion to $2.5 billion in FDI per year to achieve annual capital accumulation rates of 20-25% of GDP and annual economic growth rates of more than 5%. The island’s authorities revealed that from the passage of Law 118 until November 2020, some 180 foreign investment projects worth $7.4 billion were approved in Cuba, with more projects worth billions of dollars receiving authorization at Mariel.[3] However, these amounts refer to the total value of the deals agreed rather than to the actual capital delivered to the country. The Economist Intelligence Unit reported that between 2014 and 2020, Cuba received about $4.7 billion in FDI, or an average of $676 million per year (EIU 2020, 2019), well below the government targets.

Private entrepreneurs and cooperatives might constitute a viable complement to state-run economic activities, but so far, they have played a marginal role in the economy.

Tackling the notorious inefficiencies of the large state-owned firms that continue to dominate the Cuban economy is undoubtedly one of the most daunting challenges for the island’s government. Several state enterprises, especially in the agricultural, industrial, and tourism sectors, operate with losses while receiving hefty government subsidies. Control of business management is mainly based on centralized administrative methods instead of economic and financial methods as state firms enjoy little autonomy to manage funds and make business decisions. Private entrepreneurs and cooperatives might constitute a viable complement to state-run economic activities, but so far, they have played a marginal role in the economy. What is more, the recently eliminated dual currency system reduced the stimulating effect of salaries and underestimated the economic contribution of exporting firms while making imports seemed artificially cheap. It also generated hidden subsidies and produced distortions in almost all economic measurements to the point that it was virtually impossible to gauge the true profitability of enterprises. All of the aforementioned problems conspire against achieving higher efficiency and productivity and improving the quality of Cuban goods and services. Put simply, internal factors weigh even more heavily than external ones on the overall performance of the Cuban economy.

External Factors

In any case, external factors did in fact hit hard the Cuban economy. The Venezuelan economy has been in free fall since Nicolás Maduro assumed the presidency in April 2013, making it impossible for his government to maintain the close economic connections with Cuba built by Chavez. Venezuela’s merchandise bilateral trade with Cuba was around $2 billion in 2019, less than one-fourth its level of 2012. By 2019, Cuban exports to Venezuela had fallen nearly 90% to just $231 million while imports had plunged over 70% to $1.8 billion (ONEI 2020). Venezuelan oil shipments to Cuba decreased notably in the first half of 2019, forcing Havana’s government to enact austerity measures and step up its purchases of crude from alternative suppliers like Russia and Algeria. Shipments somehow rebounded afterward but supplies remained unreliable as the Trump administration imposed sanctions on Venezuela’s petroleum industry and on tankers transporting Venezuelan crude to Cuba[4]. Meanwhile, Cuba’s revenues from the services of its professional workers in Venezuela also declined. In short, Cuba is slowing losing a lifeline as Venezuela teeters on the brink of collapse and it is unlikely that this trend will be reversed.

It was against the backdrop of diminished Venezuelan aid and the economic squeeze from stiffened U.S. sanctions that the Covid-19 pandemic hit Cuba in the Spring of 2020 to complete a potentially devastating triple punch to the Cuban economy.

To further complicate things, the start of the Trump presidency in early 2017 put an end to two years of warming relations between Washington and Havana under the Obama administration and led to the resumption of the traditional U.S. policy of confrontation with Cuba. Obama’s measures boosted U.S.-based travel and remittances to Cuba, producing tangible economic benefits for the island and creating business opportunities for U.S. firms even if relatively few commercial deals were completed (Spadoni 2017). Trump’s measures instead caused a major drop in American travelers to Cuba by ending the popular people-to-people general license and banning U.S. cruises to the island. As a result, many small Cuban private entrepreneurs went out of business for lack of customers and earnings. Excluding Cuban Americans, the number of U.S. overnight visitors traveling to Cuba by air fell from 448,475 in 2017 to 298,269 in 2019. Arrivals of U.S. cruise passengers peaked at 341,005 in 2018 but plunged to 200,269 in 2019, as the cruise ban took effect in June of that year. To intensify economic pressure on Cuba, the Trump administration capped Cuban-American family remittances to $1,000 per quarter and, in late 2020, cut off most money transfers from the United States through formal channels by sanctioning two Cuban military-owned entities (Fincimex and American International Services) that control the remittance business in Cuba. The Trump administration also sanctioned international banks that do business with Cuba, allowed Title III of the Helms-Burton law to go into effect and, in September 2020, barred U.S. travelers from staying at Cuban state-owned hotels. In sum, Trump’s punitive measures reduced visitor flows and remittances to Cuba, hindered oil shipments to Havana, and hampered Cuba’s ability to obtain external credit and attract foreign investment (Mesa-Lago and Svejnar 2020).

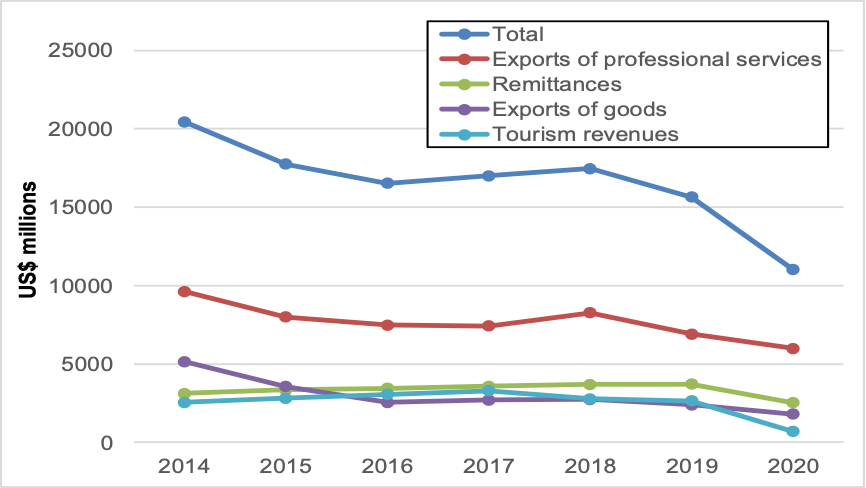

Figure 3. Cuba's Main Sources of Hard Currency, 2014-2020a

Sources: ONEI 2020, 2019; MEP 2020; Morales 2020, 2019.

Note a: Estimates for 2020.

Figure 3 provides annual data for the 2014-2020 period on Cuba’s hard currency revenues from key sources like exports of professional services, remittances, merchandise exports, and international tourism. In a sign that the Cuban economy was already in trouble, all of the aforementioned sources, with the exception of remittances, generated substantially lower revenues in 2019 than in 2018. It was against the backdrop of diminished Venezuelan aid and the economic squeeze from stiffened U.S. sanctions that the Covid-19 pandemic hit Cuba in the Spring of 2020 to complete a potentially devastating triple punch to the Cuban economy. The pandemic, without a doubt, sparked a completely new level of uncertainty by halting tourism, disrupting informal remittance channels, increasing shipping costs, and exacerbating food shortages. Furthermore, while Covid-19 gave Cuba an opportunity to send its doctors overseas for cash, Cuban exports of medical services have declined in recent years, and not only because of reduced activities in Venezuela. The number of Cuban doctors and nurses abroad plunged from more than 50,000 in 2015 to around 28,000 in 2020, mainly because they had to leave countries like Bolivia, El Salvador, Ecuador, and especially Brazil where leftist presidents lost power.[5] Thus, the coronavirus pandemic has had a significant negative impact on Cuba’s hard currency revenues. In 2020, Cuba’s total estimated hard currency earnings were around 30% lower than their level of 2019 ($4.6 billion less) and almost half their level of 2014 ($9.4 billion less).

Reforms Needed

A combination of three major external factors such as the dire economic situation in Venezuela, Trump’s hardline approach, and Covid-19 have hit Cuba extremely hard, raising the need for systemic economic reforms aimed to unleash productive forces and increase efficiency, stimulate growth, and foster sustainable development. Cuba’s initial response to the coronavirus-led economic crisis was to cut imports, revive its food rationing system, open dollar stores to capture hard currency, and suspend or delay some payments on its foreign debt. Then, in July 2020, the Cuban government unveiled sweeping economic reforms that included the promotion of small- and medium-sized private enterprises, which will be allowed to form partnerships with state and foreign companies and perform import and export operations. The reform plan also called for the creation of a wholesale market for the Cuban private sector, the expansion of non-agricultural cooperatives and self-employment, and for granting greater decision-making and operational autonomy to state firms. However, most of these measures had been announced in the past and it remains to be seen when and how they will finally be implemented. Even the long-awaited monetary and exchange rate unification, albeit needed, is a complex process that carries the risks of generating high inflation and hurting many Cubans. Time will tell whether 2021 will be for Cuba a much better year than 2020.

References

CEPAL (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe). 2020. Balance Preliminar de las Economías de América Latina y el Caribe 2020. Santiago, Chile: CEPAL.

EIU (Economist Intelligence Unit). 2020. Country Forecast: Cuba. London: EIU.

------. 2019. Country Forecast: Cuba. London: EIU.

Mesa-Lago, Carmelo, and Jan Svejnar. 2020. “The Cuban Economic Crisis: Its Causes and Possible Policies for a Transition.” Florida International University, School of International and Public Affairs, October, https://issuu.com/fiupublications/docs/20370_havel_cuba_report-issuu.

Morales, Emilio. 2020. “COVID-19 Hits the Remittance Market Hard in Latin America.” The Havana Consulting Group, March 31, http://www.thehavanaconsultinggroup.com/en-us/Articles/Article/80.

------. 2019. “Remittances, an Investment Route for Cubans?” The Havana Consulting Group, September 27, http://www.thehavanaconsultinggroup.com/en-us/Articles/Article/69.

MEP (Ministerio de Economía y Planificación). 2020. Principales Aspectos del Plan de la Economía 2021. Havana: MEP.

ONEI (Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información). 2020. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2019. Havana: ONEI.

------. 2019. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2018. Havana: ONEI.

------. 2013. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2012. Havana: ONEI.

------. 2007. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2006. Havana: ONEI.

Pérez Villanueva, Omar Everleny. 2017. “La Economía Cubana: Situación Actual y ¿Que Se Podría Hacer?” In Cuba in Transition 27, 18–29. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy, https://www.ascecuba.org/c/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/v27-perezvillanueva.pdf.

Spadoni, Paolo. 2017. “U.S.-Cuba Business Relations Under the Obama Administration and Prospects Under the Trump Administration.” In Cuba in Transition 27, 235–252. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy, https://www.ascecuba.org/c/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/v27-spadoni.pdf.

[1] Marc Frank, “Cuban Economy Shrank 11% in 2020, Government Says,” Reuters, December 17, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/cuba-economy/cuban-economy-shrank-11-in-2020-government-says-idUSL1N2IX1V9.

[2] Katell Abiven,“Pressured by US Sanctions, Cuba Struggles to Pay its Debt,” Agence France-Presse, February 22, 2020, https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/pressured-us-sanctions-cuba-struggles-pay-debts-015228669.html.

[3] Sarah Marsh, “Cuba Attracts $1.9 Billion in Foreign Investment Despite U.S. Sanctions,” Reuters, December 8, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cuba-economy-tradefair/cuba-attracts-1-9-billion-in-foreign-investment-despite-u-s-sanctions-idUSKBN28I37O; José Luis Rodriguez, “Cuba y Su Economía en 2019: Un Año de Avances en Medio de Dificultades,” Cubadebate, February 18, 2020, http://www.cubadebate.cu/opinion/2020/02/18/cuba-y-su-economia-en-2019-un-ano-de-avances-en-medio-de-dificultades-ii/.

[4] Annie Karni and Nicholas Casey, “New U.S. Sanctions Seek to Block Venezuelan Oil Shipments to Cuba,” New York Times, April 5, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/05/us/politics/trump-sanctions-venezuela-cuba.html.

[5] “Mercy and Money; Cuban Doctors,” The Economist, April 4, 2020.

Paolo Spadoni is an Associate Professor in the Department of Social Sciences at Augusta University. He received his PhD from the Department of Political Science at the University of Florida. He also holds a Master in Latin American Studies from the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Florida, and a Laurea in Political Science from the University of Urbino, Italy. Dr. Spadoni has carried out extensive research on the Cuban economy and the economic impact of U.S. sanctions against Cuba. He has published widely in scholarly and academic venues and is the author of Cuba’s Socialist Economy Today: Navigating Challenges and Change, Lynne Rienner, 2014, and of Failed Sanctions: Why the U.S. Embargo against Cuba Could Never Work, University Press of Florida, 2010.