Lagging Behind Competitors: The Cuban Tourism Industry in the Post-COVID Era

Paolo Spadoni

Augusta University

Cuba is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the Caribbean, but lately its tourism sector has performed poorly. Why is Cuba struggling far more than other Caribbean countries to recover its pre-pandemic levels of international visitor arrivals?

The information in this article is included in a forthcoming book by the author with co-author José Luis Perelló Cabrera, The Cuban Tourism Industry: Evolution, Challenges, and Prospects, to be published by Lexington Books in the first half of 2025.

Cuba is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the Caribbean, but lately its tourism sector has performed poorly. The country has attracted only negative news headlines at a time when tourism is thriving everywhere else in the Caribbean.[1] What has happened to the Cuban tourism industry? Why is Cuba struggling far more than other Caribbean countries to recover its pre-pandemic levels of international visitor arrivals?

When Things Started To Go Downhill

The last major upswing in international visitor arrivals in Cuba occurred in the post-2014 period as Barack Obama’s easing of restrictions on U.S.-based travel to Cuba fueled a sizable increase of trips to the island from the United States, especially by U.S. citizens of non-Cuban origin.

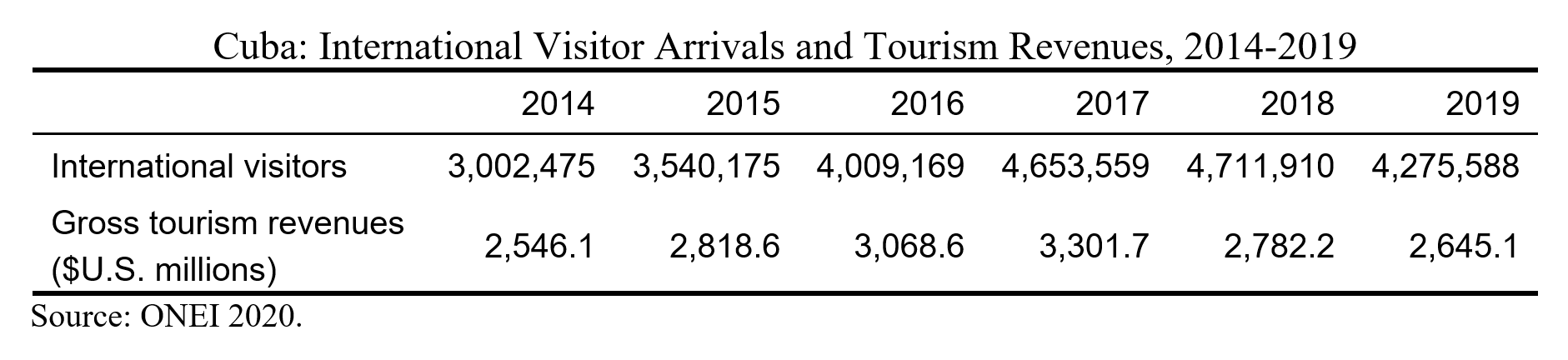

Annual overseas visitors to Cuba rose markedly between 2014 and 2017 to reach 4.65 million (Table 1). The United States alone accounted for over 40% of that growth even though there was a surge in arrivals from traditional European source markets such as Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom (ONEI 2020).

In 2018, Cuba received a record-breaking 4.71 million visitors from abroad (ONEI 2019). Yet, a closer look at these travelers - the more lucrative overnight tourism compared to the cruise tourism - reveals that the latter’s growth was the key reason that overseas arrivals in Cuba peaked in 2018. Overnight visitors to Cuba increased from 2.98 million in 2014 to 4.08 million in 2017, but dropped to 3.83 million in 2018, and remained practically unchanged in 2019. In fact, 2017 was historically the best year for Cuba’s tourism sector in terms of overnight visitor arrivals and, most importantly, generated gross hard currency revenues that reached their peak at around $3.3 billion.[2] That was the beginning of the decline of the Cuban tourism industry.

International visitors to Cuba rose slightly in 2018 thanks to booming American cruise travel, but by then the Washington-Havana rapprochement was coming to an end, as the administration of Donald Trump enacted tougher sanctions against the Cuban government. Trump had already banned individual people-to-people educational trips to Cuba in November 2017, which caused a significant drop in U.S. stay-over visitors to Cuba. In June 2019, Trump ended the general license authorizing group people-to-people trips to Cuba and banned U.S.-based cruises to the island. Cuba welcomed 4.27 million foreign visitors in 2019, a nearly 10% reduction from the previous year essentially due to Trump’s cruise ban. After 2017, overnight tourists to Cuba from European countries also fell considerably, and so did gross tourism revenues. Put simply, Cuba’s tourism sector was exhibiting clear signs of exhaustion prior to the emergence of the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Post-COVID Tourism Performance

The COVID-19 pandemic hit international travel and tourism very hard as nearly all destinations around the world were forced to put in place some kind of travel restrictions. Cuba practically maintained its borders closed to foreign tourists from March 2020 until November 2021.[3]

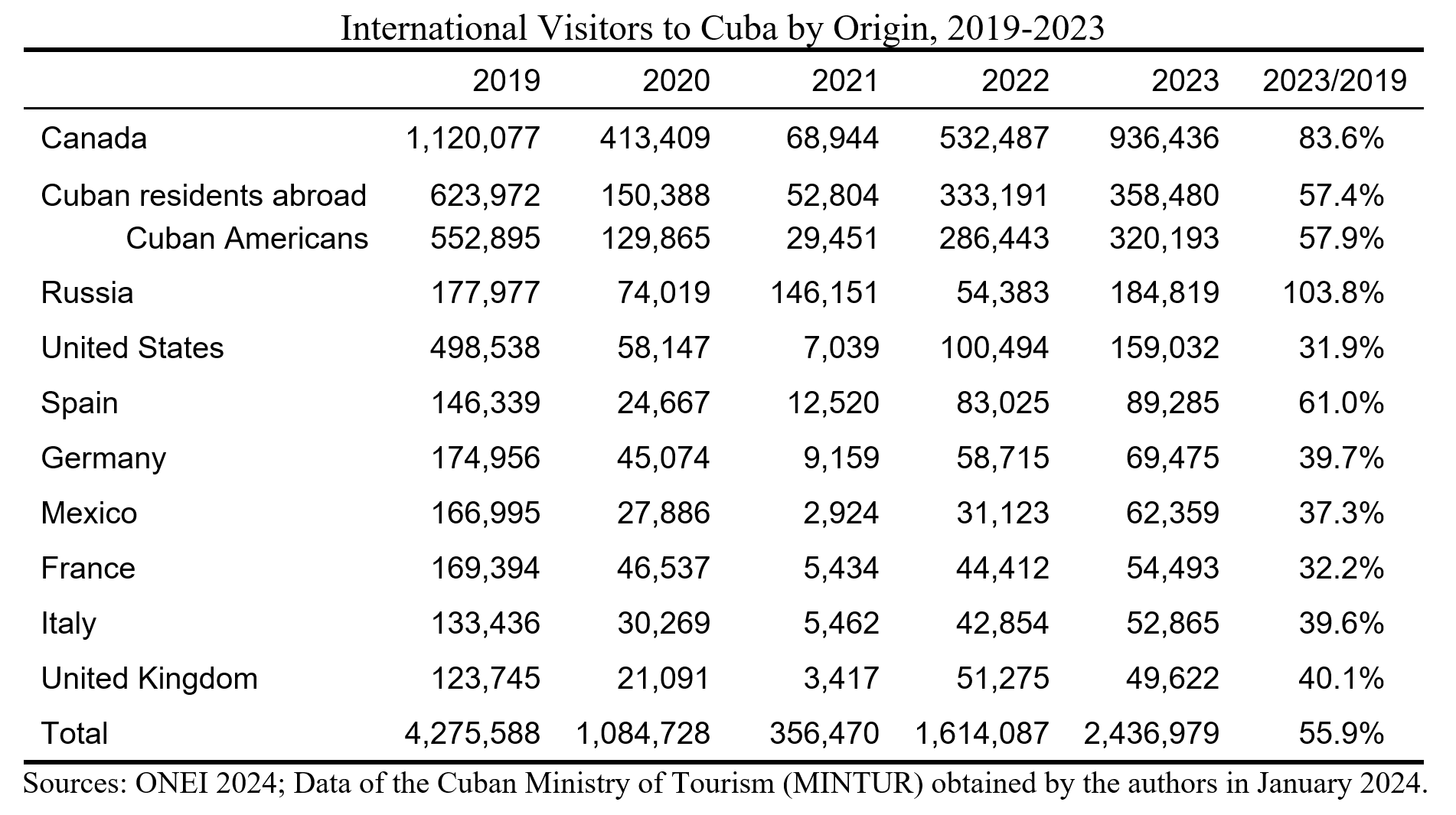

As exhibited in Table 2, international visitor arrivals (overnight and cruise travelers) to Cuba nosedived in the wake of COVID-19 from nearly 4.3 million in 2019 to less than 1.1 million in 2020 and to just about 356,000 in 2021. It should be noted that Russia was the main provider of tourists to Cuba during the critical phase of the pandemic,[4] and it has retained a key role in boosting Cuba’s ailing tourism sector.

It is not surprising that the flow of foreign tourists to Cuba experienced a drastic plunge during the worst stage of the pandemic. What is alarming, however, is that many of those tourists have not returned. With its borders reopened to tourists, Cuba received approximately 1.6 million international visitors in 2022 and little over 2.4 million visitors in 2023, representing about 56% of their level in 2019 (ONEI 2024). Furthermore, compared with 2017 and excluding U.S. citizens of non-Cuban descent, for whom traveling to Cuba had become more difficult because of Trump’s sanctions and despite the reinstatement of group people-to-people educational trips in May 2022 by the Biden administration,[5] Cuba received nearly 1.5 million fewer overnight visitors in 2023. The lost contingent of stopover visitors included 730,000 Europeans (433,000 from Western Europe), 200,000 Canadians, 300,000 Latin Americans, and even 160,000 Cuban residents abroad, mainly Cuban Americans, who could travel to the island without restrictions.[6]

Selected tourism indicators for the 2019-2023 period reported in Table 3 shed further light on the recent performance of the Cuban tourism industry. Leaving aside the disappointing numbers of inbound visitors, the average length of stay (ALOS) of stopover visitors to Cuba shot up in 2021 but by 2023 it was down to 7.5 days, lower than the ALOS in 2014-2017. Occupancy rates in four- and five-star hotels were still just above 30% in 2023. That year, gross tourism revenues were less than half their level in 2019, and revenues per tourist were the lowest since at least 1990. Meanwhile, the Cuban military continued to engage in an aggressive hotel building program, which has been criticized by many Cuban economists (Pérez Villanueva 2024).[7]

Cuba vs. Caribbean

Cuba is quite different from other tourism markets in the Caribbean, since its tourism sector operates within the framework of a centrally planned economy, and its tourism establishments are mostly owned and controlled by the State. And yet it features a commercialization scheme of a sun and beach product that it markets through the same distribution channels used by other Caribbean countries and that contributes to the region’s image as a tourist destination (Perelló Cabrera 2019).

The Caribbean’s tourism-dependent economies suffered tremendously because of COVID-19 but are recovering . In 2023, total international overnight visitor arrivals in the Caribbean finally surpassed their level in 2019 (UNWTO 2024), albeit at quite different rates across the region.

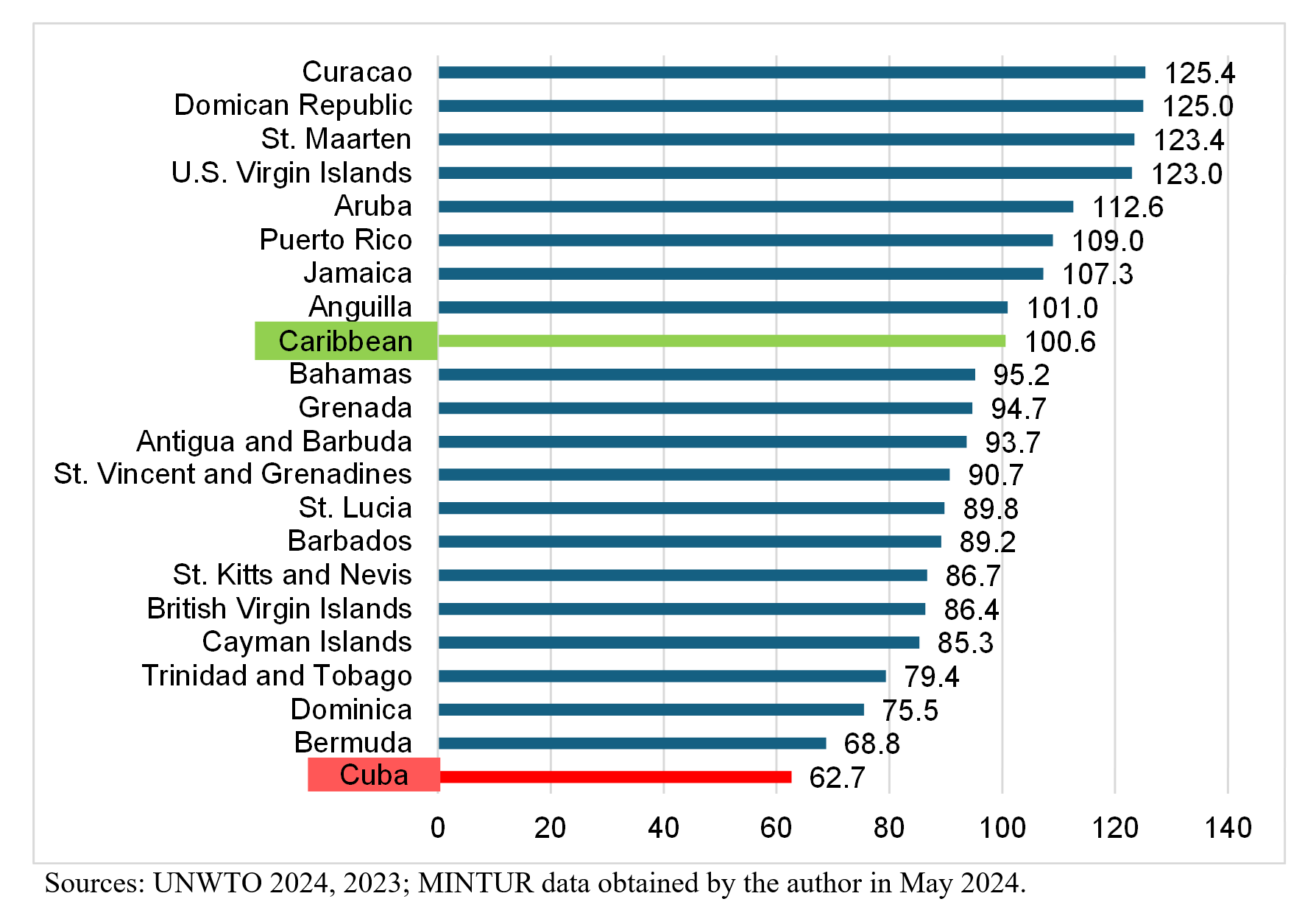

Figure 1. Overnight Visitor Arrivals to Caribbean Countries, 2023 vs. 2019

(percentages)

In 2023, overseas visitors had returned to pre-COVID levels in eight Caribbean countries: Curacao, Dominican Republic, St. Maarten, U.S. Virgin Islands, Aruba, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and Anguilla (Figure 1). The Dominican Republic and Jamaica, most notably, welcomed record numbers of international tourists. Stopover tourists in the Bahamas, Grenada, Antigua and Barbuda, St. Vincent and Grenadines, St. Lucia, and Barbados also reached about 90-95% of their pre-pandemic levels in 2023. In contrast, international tourism in 2023 in Trinidad and Tobago, Dominica, Bermuda, and Cuba, was still far from a complete recovery. Cuba, in particular, had the worst recovery performance in the entire Caribbean region, possibly with the only exception of crisis-torn Haiti.[8]

Another Difficult Year

At the end of 2023, Cuban authorities revealed that Cuba’s official goal for 2024 was to receive 3.2 million international visitors, a forecast that was later revised to a more modest 2.7 million.[9] As 2024 is coming to an end, it is virtually certain that Cuba will fail to meet both goals, and will most likely not even match the level of visitor arrivals in 2023. Again, this stands in contrast to other Caribbean countries with large tourism sectors. The Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and the Bahamas are forecasting new record-breaking years for tourism, and Puerto Rico is expected to be the Caribbean region’s most popular travel destination in the 2024 holiday season.[10]

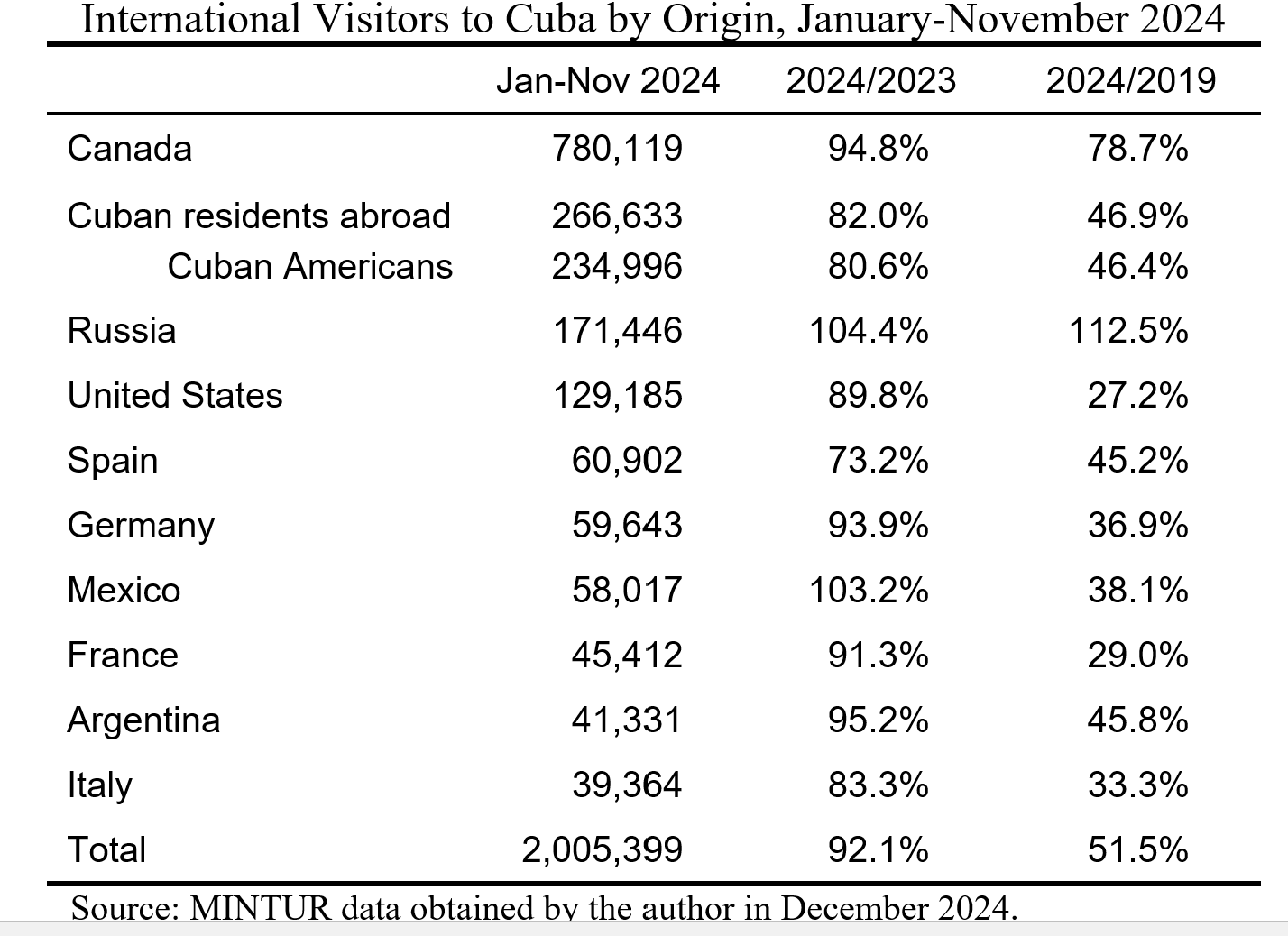

Based on the volume of arrivals in the first eleven months of this year (Table 4), Cuba should receive around 2.3 million international visitors in 2024, possibly a bit less. Since travel to the island for Americans of non-Cuban descent remains complicated and European tourist arrivals are showing no sign of a significant recovery, Cuba is pinning its hopes on the traditional Canadian market and on the burgeoning Russian market to revive its tourism sector. From January to November 2024, Russian tourists were the only major group (along with Mexico) of foreign visitors to Cuba that had surpassed their level in 2023, yet barely. Compared to the same period a year before, Cuba received less European visitors, less Cuban Americans and U.S.-citizens of non-Cuban origin, and even less Canadians. It is worth underscoring that more Canadians visited the Dominican Republic than Cuba between January and October 2024, and that Canadian arrivals in the Dominican Republic during that period were nearly 10% above their 2019 level.[11]

Among the factors that negatively affected Cuba’s tourism sector, Havana’s officials have cited Trump’s restrictions on U.S.-based travel to the island and claimed that Cuba’s inclusion in the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism resulted in Washington denying electronic visas (the Electronic System for Travel Authorization or ESTA) for travel to the United States to 300,000 European citizens who had visited Cuba.[12] It seems fair to assume that this kind of uncertainty had some real impact on potential European vacationers in Cuba and that the Cuban tourism industry has suffered significantly because of harsher U.S. sanctions, but the situation is far more complex.

A Myriad of Problems

Cuba has always attracted many tourists because of its mystique and uniqueness. This is indeed the theme of the island’s latest tourism marketing campaign Cuba Única.[13] Unfortunately, Cuba is becoming every day more unique for all the wrong reasons, and thus more unattractive as a tourist destination.

To begin with, Cuba is going through its worst economic crisis in thirty years, exemplified by plummeting real wages, frequent power outages, shortages of food, water, medicines, and fuel, crumbling infrastructures, a severe liquidity crunch, and a record-breaking mass emigration. Tourism services and companies are not spared from some of these problems.

Along with disruptions in the domestic supply of all kinds of products for Cuban hotels and a growing need to step up imports, it is estimated that around 10,000 Cuban tourism workers have switched to jobs in other sectors or left the country, all of which has led to a deterioration in the quality of tourism services (Morales 2024). Important tourist agencies reportedly have scaled back their operations in the Cuban market, among them Canada’s Sunwing Vacations, which in late 2024 decided to remove 26 hotels from its Cuba portfolio due to quality issues raised by customers.[14] To make things worse, tourists in Cuba who venture outside all-inclusive beach resorts or stay in city hotels and in casas particulares must deal with an increase in street crime that was not seen as an issue of concern until recently.[15]

In short, once potential tourists to the island start reading Cuba-related stories about nationwide blackouts, aviation fuel shortages affecting international flights, food and water supplies running low at hotels, shortages of antibiotics, street gangs engaging in theft and violence, and the Oropuche virus outbreak, just to cite some recent problems highlighted in the news, they may well decide to stay away from Cuba and vacation somewhere else. Moreover, it is telling that a growing number of Cuban residents abroad, especially those living in the United States, prefer to invite their Cuban relatives from the island to spend their vacations not in Cuba but in hotels in Punta Cana (Dominican Republic) and Cancun (Perelló Cabrera 2024). Between January and October 2024, some 85,000 Cuban citizens traveled to the Dominican Republic, as compared to 34,000 during the same period in 2019, when a record number of Cuban Americans visited Cuba.[16]

And then there are all the problems that have plagued Cuba’s tourism sector for decades, from widespread inefficiencies and low profitability to insufficient service standards, supply chain instability, and difficulties adapting to new tourism trends. While external factors like stiffened U.S. sanctions certainly hurt Cuba’s post-COVID tourism performance, the aforesaid problems have to do with ill-conceived policies, the island’s outdated tourism model, and structural constraints of the Cuban economy.

Critical shortcomings of the Cuban tourism industry include poor integration within the Caribbean region that could help promote multi-destination programs, a weak legal framework, entrenched prejudices of Cuban authorities about foreign investment and market capitalism, a tourism model overly focused on sun-and-beach tourism and a massive building of hotel rooms growing at a rate in excess of tourist demand, and a tourism sector inserted into a state-dominated economy with chronic systemic flaws. Now that Trump is on his way back to the White House and the Cuban economy is on the ropes, it is most urgent than ever that Cuba adopt structural economic reforms and a new tourism development strategy to improve the tourism industry’s functioning and competitiveness in the Caribbean marketplace, and ensure a brighter future for international tourism in Cuba.

References

Morales, Emilio. “GAESA También Apaga la Industria Turística,” Cuba Siglo 21, N.28, November.

ONEI (Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información). 2024. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2023. Havana: ONEI.

------. 2023. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2022. Havana: ONEI.

------. 2020. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2019. Havana: ONEI.

------. 2019. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2018. Havana: ONEI.

Perelló Cabrera, José Luis. 2024. “Luces y Sombras del Turismo en Cuba: La Década Perdida,” Progreso Weekly, December.

------. 2019. “El Turismo en Cuba: Cambios y Tendencias,” Horizonte Cubano, Columbia Law School, March 9.

Pérez Villanueva, Omar Everleny. 2024. “El Turismo en Cuba, una Locomotora Sin Vagones,” La Joven Cuba, May 7.

UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization). 2024. World Tourism Barometer. Madrid: UNWTO, Volume 22, Issue 2, May.

------. 2023. World Tourism Barometer. Madrid: UNWTO, Volume 21, Issue 4, November.

[1] Will Grant, “Hit by Blackouts, Cuba’s Tourism Industry Now Braces for Trump,” BBC News, December 9, 2024; Ed Augustin, “No Mojitos and No Lights: Cuba’s Tourism Industry Fights Losing Battle,” Financial Times, November 2024; Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO), “Caribbean Tourism Experiences Strong Growth in 2023, Recovery To Continue Into 2024,” CTO News, March 15, 2024.

[2] Carmen Sesin, “Sharp Decline in U.S. Travel to Cuba Spurs Overall Drop in Tourism for the Island,” NBC News, April 25, 2018.

[3] Andrea Rodríguez, “Now Largely Vaccinated, Cubans Prepare to Welcome Visitors,” Associated Press, November 8, 2021.

[4] “Over 130 Russian Tourists Remain Isolated on Cuba over Suspected Covid – Consul General,” Russian News Agency TASS, July 5, 2021.

[5] David E. Sanger, “Biden Administration Lifting Some Trump-Era Restrictions on Cuba,” New York Times, May 16, 2022.

[6] Eyder Peralta, “Three Things to Know about the Current Crisis in Haiti,” NPR, March 6, 2024.

[7] “Cuba Recibió 1,7 Millones de Turistas Entre Enero y Septiembre, Un 5,2 % Interanual Menos,” EFE, November 5, 2024.

[8] Lebawit Lily Girma, “Puerto Rico Is a Floating Island of Desirability,” Bloomberg, November 25, 2024.

[9] Calculations of the author from data of the Cuban Ministry of Tourism (MINTUR) obtained in May 2024.

[10] “Casi 1.500 Millones de Dólares en Dos Años: La Innecesaria Inversión del Gobierno Cubano en Turismo,” Diario de Cuba, May 12, 2022.

[11] Tourism statistics of the Central Bank of the Dominican Republic.

[12] “Cuban Foreign Minister Denounces Extraterritoriality of US Blockade,” Cuban News Agency, May 1, 2024.

[13] Samantha Mayling, “New Cuban Campaign Highlights ‘Unique’ Tourism Offerings,” Travel Weekly, September 14, 2022.

[14] Michael Pihach, “With Cuba in Damage Control, Sunwing Shifts Focus to ‘Hidden Gems:’ 26 Cuban Hotels Removed,” Pax News, November 15, 2024.

[15] Will Grant, “’The Violence is Getting Out of Hand’: Crime Grips Cuba’s Streets,” BBC News, September 24, 2024; Carla Gloria Colomé, “Cuba, el País ‘Más Seguro del Mundo’ Es Cada Vez Más Inseguro,” El País, June 17, 2024.

[16] See supra note 10.

Paolo Spadoni is an Associate Professor in the Department of Social Sciences at Augusta University. He has published widely in scholarly and academic venues and is the author of Cuba’s Socialist Economy Today: Navigating Challenges and Change, Lynne Rienner, 2014, and of Failed Sanctions: Why the U.S. Embargo against Cuba Could Never Work, University Press of Florida, 2010. Dr. Spadoni’s new book (with José Luis Perelló Cabrera), The Cuban Tourism Industry: Evolution, Challenges, and Prospects, will be published by Lexington Books in the first half of 2025.