Is There Room for Improving Retail Sales in Foreign Currency?

Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva

We must seek and implement alternative solutions with boldness and decisiveness.

Beyond the debate around their possible underlying causes, the July 11th protests in Cuba have shown that people are unhappy about the lack of food and personal hygiene products, housing problems, pandemic exhaustion and power outages, all of which are attributed to the US embargo.

However, that discontent is also due to internal improvisations, excessive planning, and obstacles placed on private and state productive forces by the government. So now is a moment when the state must be much more proactive and listen to the opinions of its many economists and actually consider their recommendations.

We continue to see the repercussions of preserving the state monopoly over foreign trade. However, there is another, less-discussed state monopoly that currently may have more negative effects than advantages: the monopoly on retail sales.

In the short term, there are several possible reasons for the reluctance by the state to make changes to its system of retail sales in foreign currencies:

- A fear that allowing other entities to operate in the retail space will allow them to capture the largest percentage of the market, causing state enterprises to lose considerable market share and profits to apply to state purposes.

- External competition may make it impossible for state enterprises to apply prices with high cost-value ratios, as they currently do, decreasing the country's profits from these operations.

- Authorized foreign companies would likely repatriate the majority of their profits, thus increasing financial flows abroad of hard currency.

Before considering the reasoning by the state as to why it cannot loosen its grip on retail sales, let’s recall that a few months ago the government also had to consider whether it would only keep stores that sold products exclusively in Cuban convertible pesos (CUC) or in Cuban pesos (CUP)—and then only in CUP after the elimination of the CUC—or if it would allow sales in freely convertible currency represented by a debit card, known as moneda libremente convertible (MLC) without a cash feature.

The measure had complex political implications. For instance, most people would be unhappy if products were not sold in the country’s currency—the currency in which they receive their wages. But it was clear that something had to be done: foreign currency was not being deposited in exchange for MLC at the state exchange bureaus (CADECA) at the same rate as when they were used to purchase CUCs. And the products sold in stores in CUC required the state to pay suppliers in greater amounts of convertible currency – funds that then would not flow to the state coffers.

The use of the MLC was, and continues to be, a necessary measure (although there is disagreement on this) when you take into account the various factors below that did not exist back when state stores began accepting foreign currencies in 1993:

- It is impossible to use Cuban pesos to buy foreign currency at the state exchange bureaus (CADECA), and in order to purchase MLC to meet needs that require it; people must turn to an increasingly expensive and risky unofficial market.

- There are now unprecedented shortages in the stores that sell products in MLC, and long queues to buy whatever is available.

- Product prices are much higher than what has been customary since 1993 for a wide range of products, the costs of which would not have risen so significantly. For example, domestic beer, which for years was sold at 1 CUC, is now selling in MLC at 1.30, and has been as high as 1.40 MLC.

- Bonuses in foreign currency for workers in certain prioritized economic sectors with enterprises able to generate their own foreign currency and external liquidity have been eliminated.

- There are long queues for depositing foreign currency in banks, which likely discourage deposits.

- There are recurring technological problems with the electronic connection at the store checkout counters.

For many years stores accepted US dollars (USD), and later CUC; but neither were currencies in which Cuban workers received wages. So the concept of MLC stores is not such a new one so as to elicit such widespread popular rejection. While these stores do not sell in the same currency as wages are paid - an understandable objection - they are not something new in Cuba’s history.

The explanation that is given for the frequently out of stock products in the MLC stores is that the U.S. embargo limits access to distributors and blocks the ability to pay suppliers outside of Cuba. Will we really continue to blame the U.S. embargo for the empty shelves and long lines at the MLC stores? Or, should we boldly and decisively seek and implement alternative solutions?

Understandably, the government has been reluctant to approve the reinstatement of the hard currency sales by means of the MLC stores. And approving the entry of foreign enterprises to engage in retail business in Cuba may also be distressing. The question is: What prevents it?

The formation of Cuban enterprises, with totally foreign or mixed capital, licensed for retail sales in Cuba, could bring the following advantages:

- These enterprises would have a better chance of supplying local markets with products from their operations abroad, thereby avoiding the embargo.

- They could serve as a sales channel for family members outside of Cuba to provide products for their Cuban relatives without the costs and hassle of sending remittances.

- They could allow for greater use by external buyers of international credit cards to make online sales for the Cuban relatives.

- They may extend financing to Cuban, state, and private producers by purchasing their products for resale in their stores.

- The state would eliminate the issues of regular product shortages in stores, losses and syphoning of products into the black market, warehouse logistics, and the capital expenses of store repairs, marketing costs, etc.

- Foreign retail chain stores would have better payment capacity and would not need to request long commercial credit terms from suppliers. This would translate to better prices, which would be beneficial to Cuban consumers.

- The foreign retailers could actually generate more income for Cuba in taxes and fees.

Let us not forget the existence of a Foreign Investment Law that allows for the creation of an enterprise of Cuban nationality, with joint or 100% foreign capital. These enterprises are authorized to lease or build premises, or receive them as an in-kind property contribution from the Cuban partner, in the case of joint ventures. And they may receive a license to import and export relevant goods. It is true that the greatest difficulty consists in obtaining a liquidity certificate to repatriate the dividends from the profits obtained, which is one of the current obstacles to foreign investment in Cuba. But that is an operational matter, not a legal problem. The law itself recognizes investors’ rights to repatriate profits from their businesses in Cuba.

Some may think that if the stores belonging to the GAESA group (Grupo de Administración Empresarial S.A.) and other state business groups cannot improve the current cost-value ratios, it would be very difficult for a foreign enterprise entering the Cuban retail sector to do so and bring greater economic benefits to the country.

Suppose a product that costs USD 100 has a coefficient of 2.4 and is sold in MLC stores for USD 240. This margin—2.4 times or 140% above cost—is equivalent to a commercial margin on sales of 58.3% [(240–100) / 240].

But the above represents a gross margin from which operating costs and expenses must still be deducted, such as salaries, amortization of fixed assets, marketing, logistics, transportation costs, storage, distribution, insurance, losses, electricity, water, fuel, among others.

What these costs and expenses represent as a factor of the total sales in MLC for Cuban chain stores (CIMEX, TRD, Caracol, PALCO) is not publicly available. But the government does have that information. If we imagine that they represent, on average, 25% of total sales, this would give a net margin on sales of 33.3% (58.3–25). Or the equivalent: [240–100–60) / 240 = 33.3%; where 60 represents 25% of 240.

In theory, this net margin is the utility or profit that would belong to the State as the owner of those chain stores. We say “in theory” because there is the factor of the labor expenses which are accounted for in USD, but in reality paid to workers as wages in domestic currency. There may be other expenses that receive a similar treatment.

The 33.3% profit margin on sales is significant: it seems impossible to forego it in light of all of the Cuban State’s plans and budgetary needs. However, we forget that the finance ministries in countries with capitalist economies often receive very large revenues in the form of a value added taxes (VAT). In some nations, this tax can be up to 21% on the added value of a product, although the percentage of taxes may differ depending on the types of products.

If foreign enterprises are allowed to enter the retail sector, we can let the companies themselves set their prices in accordance with their sales policies. And if these companies are required by law to add a sales tax (which is not VAT) of 30–35% to the sales price, the state would be receiving the same percentage of profit that it currently receives from its own chain stores.

The state would not have to deal with circumventing the embargo, the current difficulties of buying and paying abroad, plant maintenance, workforce management, investments, logistics of storage and transportation, thefts and losses, among other issues.

In addition to the foreign exchange earnings generated from charging for electricity, water, fuel, and other utilities, the country could obtain additional income by leasing store locations to the foreign enterprises or from the investment process of the enterprises building new retail stores.

Let us consider the impact on the final prices for Cuban buyers by returning to our example of the product that costs USD 100. If the foreign retail chain sets a target profit margin of 40% on sales, the retail selling price would be USD 166.70. If the chain must add a sales tax of 30% on behalf of the Cuban National Tax Administration Office, the final selling price would be USD 216.70. Even with a 35% tax, the product price of the foreign retailer would result in an after tax price of USD 225.05, which would be less than the price of USD 240 we calculated above for the Cuban retail model, which reflects a coefficient of 2.4 over costs.

Suppose that the same bottle of beer we discussed above had a purchase cost of USD 0.35 and that the foreign retail chain applied the same 40% margin on sales, it would sell the beer at USD 0.60. Considering that it is an alcoholic beverage, and therefore there is a social goal of not stimulating its consumption, and that higher taxes could be obtained from selling it, setting a final price of USD 1 the result is a 66.6% tax on beer. This differential taxing approach would also allow for lower sales taxes to be applied to products consumers prioritize—such as oil and chicken—that are more expensive, where a tax of 30–35% would result in a higher sales price than is currently the case.

In addition to approving enterprises with totally foreign capital, we could consider joint enterprises with a certain percentage of participation by Cuban entities (not a majority, so as not to discourage foreign partners). Cuba's capital contribution could be the surface rights for those store locations for a specified period of time. At the end of the specified period, the state could begin receiving leasing revenue.

It would not matter so much that the Cuban chain stores’ market shares decreases if: its stores are better supplied and customers are more satisfied; shortages in stores are eliminated; and the overall sales volume increases, and with it, the country’s overall net income. It would not mean a reduction in the state's net margins as a percentage of sales. And the flows of funds abroad would stem from future sales at these foreign retail chain stores, without negatively impacting the country’s funds derived from other sources.

Last, but not least, is how we should select partners that are committed, willing, and able to meet the objectives Cuba sets. There are important retail chains in many countries, with interlocked distribution chains and structural ties to all sorts of producers, with their own brands (private labels) and manufacturers' brands. It should not be very difficult to negotiate Cuba’s attracting some of these chain stores.

For example, Carrefour (France), Mercadona o Dia (Spain), Lidl (Germany, which is within the Schwarz Group), Chedraui (Mexico), Spar (Holland). We need to mention the American chains that are among the largest in the world, and which, when they see this niche market flowing to international competitors, could pressure OFAC (the US Office of Foreign Asset Control) to obtain licenses and establish themselves in Cuba, thus paring back the embargo laws. It would be inadvisable to jump from one (state) monopoly (the Cuban state) to another (foreign retail) monopoly. For healthy competition to exist—which benefits the Cuban people and the national economy—several retail store chains should be approved, and from as many countries as possible.

Of course, this does not mean that we should close the national chain stores. But they will have to adapt to work more efficiently and compete with the foreign chains.

The United States’ framework of laws that is the embargo has greatly damaged Cuba, and no matter how much clamoring there is to lift the embargo, or to appeal to international solidarity, that decision to eliminate it does not lie with the Cuban government. But the decision to find effective solutions to combat its effects does. What we propose here could indeed be one solution.

The shortage of products in Cuban retail stores only stimulates the purchase of products from foreign companies through a complex import scheme, online sales, and donations from the outside buyers to relatives in Cuba. While these options provide a partial solution, improving conditions for some producers, they also: 1) provide greater advantages to the sector of the population with relatives willing to make purchases from abroad; 2) transfer most of the profit to the foreign enterprises fulfilling orders instead of to the Cuban State; and 3) their high margin reduce the purchasing power by the Cuban people and their families offering assistance from abroad. The products’ final prices obtained through the alternative schemes are usually much more expensive than the prices for those products in Cuban state stores. There is no doubt that it would be better for the country to have retail stores administered by foreign enterprises rather than continue to watch product sales increase through the alternative sales scheme.

However, at the moment, decision-makers may be considering closing the MLC stores, as most Cubans dislike them. That would be equivalent, in our opinion, to “throwing the baby out with the bath water”. A country with only a single currency, one’s own, used in its stores is, of course, desirable and normal in any economy. But, first the country must have a floating exchange rate. Except for China and Vietnam after their economic reforms, no socialist or former socialist country in Europe adequately addressed this problem, ignoring that money is just another commodity and setting long-term fixed exchange rates that were far from the economic reality.

If stores are only established in CUP, it is to be expected that almost no one will bring their convertible currencies to banks. They will exchange them on the informal market at better rates; products will be purchased with CUP obtained in that way, but the Cuban chain stores will not have foreign currency to import merchandise, thus increasing shortages in stores. That definitely does not seem to be the solution.

It is very clear that there should only be one currency in circulation and that there should be no stores selling in either CUP or MLC. We wish that were the case. Yet in Cuba we have never known how to manage the currency’s convertibility or been willing to allow the value of the national currency to float against foreign currencies according to market conditions.

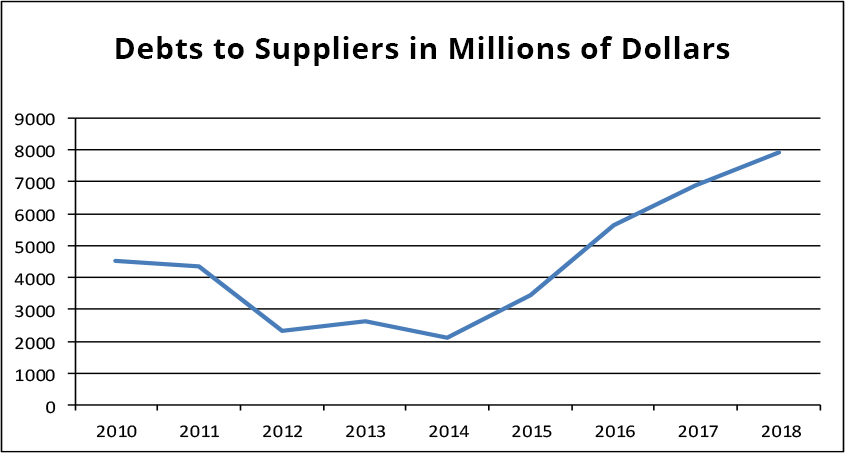

Cuba already has enormous debts to suppliers for merchandise already sold in stores in CUC for which it could not pay. This graph shows these debts through 2018, which suggests that during the last two years the debts continued to grow. Will they again try to use the same procedure to buy imported goods? Will we once again forget why we turned to stores selling in USD in 1993, and eliminate the current ones without creating the other economic conditions necessary to have stores selling only in the national currency?

The most complex thing to analyze is not the amount of revenue to be obtained by the Cuban State, that is, whether it is going to be higher or lower than today. The problem is that we can assume, with some certainty, that a major foreign chain will not want to have a Cuban enterprise subjected to pressure from OFAC if it operates through a joint venture with a Cuban partner. The foreign chains will not hesitate to collect and transmit to the Cuban Treasury the sales taxes that it establishes.

The question is: Will GAESA be willing to give up this important income source, ceasing to be the important contributor of foreign currency to the State that it is today, for the benefit of the country?