Challenges for the Private Sector in the Cuban Economic Model. Part Two

Not only is the regulatory framework rudimentary, but the rules can change arbitrarily thanks to the state’s almost total discretion to make pronouncements on economic policy and government activity in general.

Second of two parts

Private Enterprise in the Cuban Model

The expansion of the private sector in Cuba faces many challenges. Although the term is used generically, private ownership of the means of production in Cuba has specific characteristics that prevent it from being fully comparable to that in other economies. The exercise of typical ownership rights (right to residual income, conveyance rights, and management rights) is severely restricted.[1]

Generally, the private sector in Cuba includes agricultural cooperatives and independent farmers, self-employed workers, owners and employees of private companies (micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), artists, and a sizeable sector of creative and cultural enterprises. Such activity takes place, in many cases, in a legal and regulatory limbo.

All operate in an economic system in which they are only recognized as having a secondary role and which lacks the minimal formal institutions to properly support their development and operation (Torres, López, & Orta, 2021). The supposed superiority of state-bureaucratic ownership of the means of production has not been proven to succeed in any of the countries and during the decades in which it has existed. Cuba has not been the exception.

Not only is the regulatory framework rudimentary, but the rules can change arbitrarily thanks to the state’s almost total discretion to make pronouncements on economic policy and government activity in general. In the case of self-employed workers and MSMEs, the state places enormous restrictions on their purchase and sale of real property and prohibits them from leasing. In addition, access to capital goods is very limited.[2] Nonetheless, it can no longer be said that the private sector is a residual or relatively small segment within the country’s general productive activity.

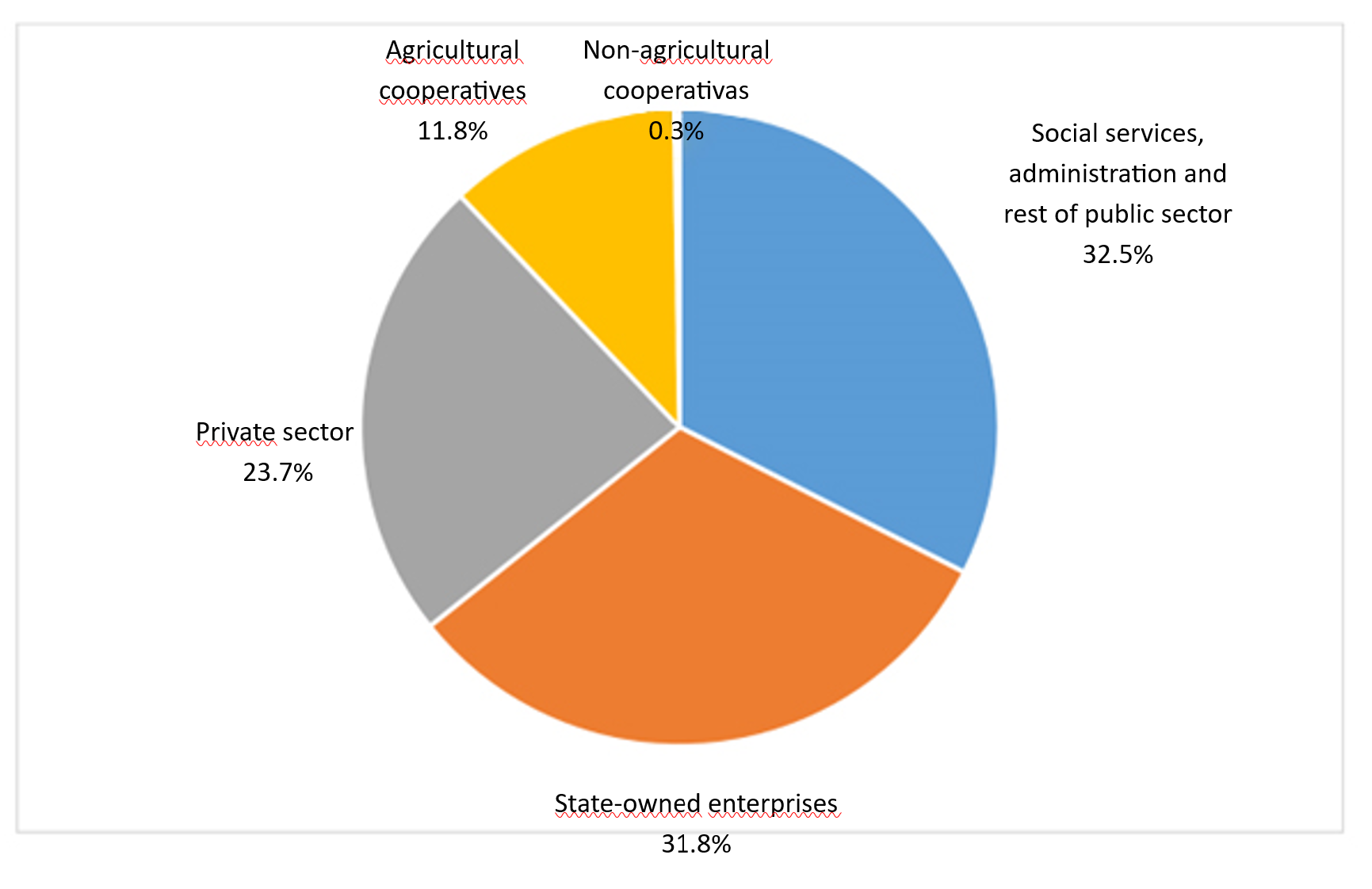

The following graph shows the formal employee structure in terms of employment percentages.

Figure 1. Cuba: employment structure (formal employees) according to type of ownership in 2022

Source: Created by the author, based on National Bureau of Statistics and Information (ONEI), various years, and Odriozola, 2023. The figures are not exact because they combine different sources from different years.

These figures serve as the basis for discussing some interesting ideas.[3] Viewed as a whole, the non-state sector (private enterprises and cooperatives) provides employment to 35.8% of the total number of recognized employees in Cuba. This percentage already exceeds or is very close to that of employees of state-owned enterprises.[4] As an employer, the state-owned enterprise is no longer the dominant player in productive activity, or will cease to be so in the very short term.

It does, however, continue to appear dominant in other indices, such as those of value-added services or exports. Nevertheless, a review of the total number of employees and other indices incorrectly portrays an outsized image of the productivity of the state-owned enterprise. According to official data, 80% of the sector’s profits are generated by 56 state-owned enterprises (out of a total of approximately 2,417), only 16% carry out an export activity and 80% of export activity is concentrated in 12 companies.

The number of state-owned enterprises that posted losses in 2021 were 500, while in 2023 there were 278. But these numbers are misleading due to the prevalence of soft financial restrictions (González & Torres, 2024). In practice, a disproportionate share of productive state-owned enterprise activity is concentrated in a very small number of entities. On the other hand, the existence of underemployment (the so-called “bloated payrolls”) in the public sector has been widely documented, and is estimated at almost 30% of the total number of employees (Mesa-Lago, 2023).

The size of the private sector is not limited to government authorized activity. It is a well-known fact that, for various reasons, including the limitations of the current regulations, there is a sizeable private sector involved in informal activity associated to the government authorized private activity. Likewise, informal activity per se, that which is not linked to the authorized private sector, has been and continues to be substantial in Cuba. Part of the informal private activity engages in the marketing of scarce products, which have been pilfered from state-owned enterprises, but which are also imported by individuals in accompanying luggage. In a different economic and political environment, most of this activity would be authorized. Since 2011, when more formal private activity was authorized, the informal economic activity decreased substantially, from 76% that year to 65% in 2022 (National Bureau of Statistics and Information (ONEI), various years).

Moreover, the private sector plays a critical role in specific areas of the economy. After almost thirty years of the state-owned enterprise's dominance in the area of agriculture, the quest for increased self-sufficiency in food production in the midst of the deep economic crisis of the early 1990s was decisively answered by the expansion of cooperatives and independent farmers. When Raúl Castro's government complained about the high levels of food imports, Cuban economists proposed handing over unused lands to farmers and farm cooperatives on an usufruct basis and selling surpluses (after meeting the quota for delivery to the state) on the open market. When it became necessary to create jobs and guarantee the provision of goods and services that are usually considered of little strategic value—restaurants, cafés and household and personal services—the alternative was, and continues to be, the private sector. That was the case in 1993, and also in 2010.

Private productive activity goes hand in hand with an expansion of the market as an allocation mechanism, rather than one of bureaucratic coordination, as is typical in a socialist system. Private enterprises structure their operation around an autonomous and independent decision-making process, based on interpreting the “signals” received from the economy, most of which are transmitted through market pricing.

The rigid pricing imposed by socialist central planning does not work for these services described above. At the same time, the private enterprise, whose primary objective is to earn enough profits to be in the black, demands the ability to determine autonomously the number of its employees, their salaries, and the prices at which it sells its output at levels consistent with the primary objective of being “in the black”.

Cuban authorities view this reality with a mixture of perplexity and skepticism. Historically, their stance towards the private sector has oscillated between grudging acceptance and open hostility, which has prevented the drafting and consistent implementation of policies that would drive consistent socioeconomic development.

Final thoughts

Despite an adverse regulatory, ideological and political environment, the role of the private sector has not diminished in recent decades. As a result of the discretionary nature of the socialist decision-making paradigm and the design of public policies in Cuba, private resources are mobilized at levels well below their true potential. Long-term capital investment entails a level of predictability and a rate of return that is not possible under the conditions of the current model.

With the aim of contributing to the organic growth of a private sector based on transparent rules, the following measures are proposed, none of which involves tapping state-owned resources:

- Eliminate current bureaucratic-administrative procedures for the approval of private enterprises. Once the legal requirements for the establishment of a company have been met, which requires a clerical determination, the approval should be granted. This principle of establishing clear rules that are confirmed by the administrative agency should also be used for the granting of all required ancillary permits, which will vary in number and complexity depending on the type of activity.

- Use practical flexibility as regards both approval of and the amendments to the company’s purpose clause in its organizational documents. Avoid including clauses that alarm investors such as “…at present, that is not a government priority.” Small businesses reinvent themselves several times, as they grow and identify strategic errors in their business plans, and change their company purposes frequently to adapt to the economic environment.

- Reduce the list of “prohibited” activities to a minimum, and, in particular authorize professional and financial services to be provided by the private sector.

- Implement a transparent and rational legal framework allowing foreign investment in private enterprises.

- Eliminate the current requirement of intermediation by state-owned enterprises for foreign trade operations. It should be up to the private enterprise to decide whether or not it wishes to retain the services of state-owned entities, based on the offered services. Likewise, the organization of private MSMEs, specializing in foreign trade-related activities should be allowed.

- Restructure the tax framework according to generally accepted taxation principles, and adapt it to the specific circumstances of the Island. Taxes do not just serve to finance the state, but must also be a tool to implement public policies.

The above list is by no means exhaustive, and its proposals may be adopted separately and in advance of implementing other structural reforms that the economy desperately needs. One clear example would be the formation of a formal currency exchange market that reflects the balances of trade affecting individuals and the MSME sector. Another would be the restructuring of the current regulatory framework that encourages many individuals and MSMEs to market imported merchandise instead of producing it locally. In addition to official resistance, many citizens who thus far do not directly benefit from the development of the market sector have misgivings about the necessary changes – which is understandable. However, it is unlikely that the current economic crisis can be overcome by continuing to impose unnecessary restrictions on the private sector.

The previous proposals are measures that, regardless of the adverse foreign environment—including U.S. sanctions—the country can take independently to boost domestic productive activity.

References

Díaz, I. (2023). Micro, pequeñas y medianas empresas en Cuba. Presentación a la Red de Investigadores Cubanos (CLALS, American University), La Habana.

González, R., & Torres, R. (2024). Removiendo Restricciones Presupuestarias Blandas en Cuba: Hacia una Reforma Productiva Real. Washington DC: Red de Investigadores Cubanos (Center for Latin American and Latino Studies, American University).

Kornai, J. (1992). The Socialist System. The Political Economy of Communism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kornai, J. (2008). From Socialism to Capitalism. Eight Essays. Budapest: Central European University Press.

Mesa-Lago, C. (9 de enero de 2023). El impacto social de la crisi económica en Cuba. El Toque. Obtenido de https://eltoque.com/el-impacto-social-de-la-crisis-economica-en-cuba

Mizsei, K. (1992). Privatization in Eastern Europe: A Comparative Study of Poland and Hungary. Soviet Studies, 44(2).

Odriozola, J. (21 de junio de 2023). Miradas a la empresa estatal: Lo que tenemos y lo que queremos. Cubadebate. Obtenido de http://www.cubadebate.cu/noticias/2023/06/21/miradas-a-la-empresa-estatal-lo-que-tenemos-y-lo-que-queremos-video/

Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información (ONEI). (varios años). Anuario Estadístico de Cuba. La Habana: ONEI.

Pérez-López, J. F. (1995). Cuba's Second Economy. From Behind the Scenes to Center Stage. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Torres, R., & Fernández, O. (2020). El sector privado en el nuevo modelo económico cubano. Estudios del Desarrollo Social: Cuba y América Latina, 8(3).

Torres, R., Cruz, K., & Carmona, M. (2022). Fuentes de oferta y demanda del mercado informal de divisas en Cuba. Estudios del Desarrollo Social: Cuba y América Latina, 10(1).

Torres, R., López, D., & Orta, A. (2021). Cuentapropismo y su marco regulatorio: una mirada desde el ecosistema emprendedor en Cuba. COFIN HABANA(15 (especial)).

[1] All countries have restrictions on the exercise of these rights, for reasons of the public good and because on many occasions their enjoyment can interfere with the ability of others to exercise their own.

[2] This is as a result of problems of various kinds, among them the lack of an official foreign exchange market. The foreign currency credits offered bybanks have terms of up to one year, which means that they cannot be used for the purchase of machinery. More recently, the purchase of transport vehicles (cars and trucks) was authorized.

[3] According to data from 2023, MSMEs are probably employing a little more than 200,000 people (Díaz, 2023), although these data are compiled from members’ statements at the time of organization of the enterprises. The reality can be very different. “Classic self-employment” continues to be a very relevant source of employment. In accordance with current legislation, MSMEs have to send, on a quarterly basis, updated information containing data on the number of workers, sales, etc. Although the data is limited to aspects of employment and production, the Bureau of Statistics should publish this information to facilitate more rigorous analyses.

[4] Another argument could be how to properly categorize the so-called Basic Cooperative Production Units (UBPC). Legally speaking, they are independent cooperatives, but given the limitation on their exercise of typical ownership rights, they are closer to state-owned companies.