Tourism in Cuba: Changes and Tendencies

Cuba's new stage of tourism development will feature a move from a traditional model of sun and sand to an intensive one of diverse offerings addressing new demands.

Cuba is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the Caribbean. The rapprochement between Cuba and the United States created the prospect of a tourist boom to the Caribbean’s biggest island that could have been a veritable gamechanger.

Cuba features a commercialization scheme based on a primary product—sun and sand—operated through the same distribution channels that control the destination tourist markets, the airlines, and the presence of international hotel brands that make up the sub-region’s tourist image. Moreover, Cuba is unique in the fact that it is a destination country subject to a restrictive policy from the region’s principal origination market: the United States. This same country is the principal recipient of Cuban immigrants.

In Cuba, tourism has had different phases of development which are deeply related to the political situation with the United States. In this sense, it is affirmed that the neighbor to the north is Cuba’s “natural market.”

Following the Second World War, Havana experienced a surge in tourist activity with a new cycle of investments in hotels and a growth in tourist flows, with the opening of casinos in the 1950s adding to the attraction.

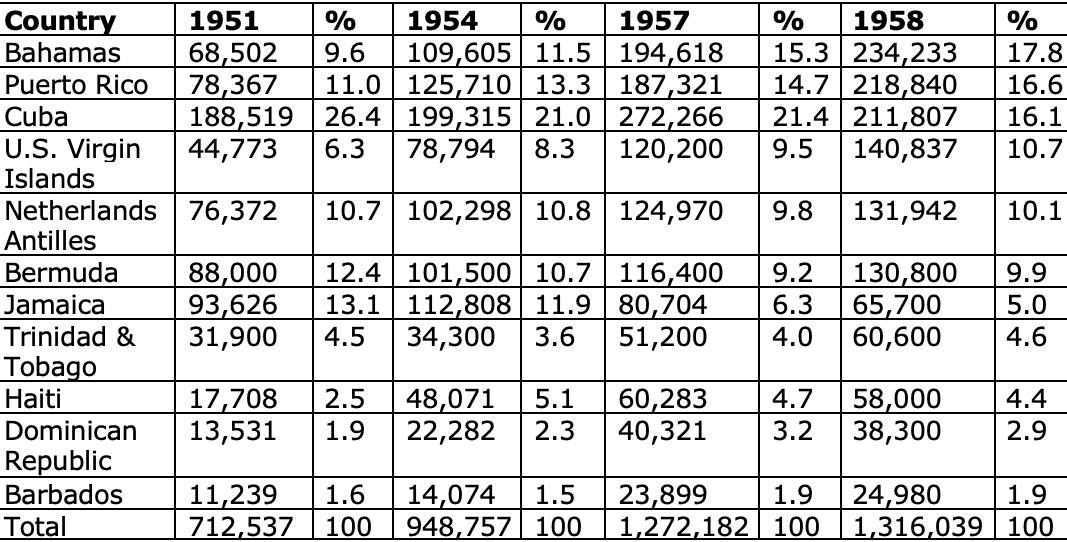

Table 1. Tourist Arrivals to Major Caribbean Countries (1951-1958)

Source: Villalba Garrido (1993)

In 1958, there were reported to be 7,728 rooms in 128 hotels in Cuba: 4,892 in Havana and 702 in Varadero. 72% of the total hotel capacity was concentrated in these two localities. The remaining 28% was dispersed through the other regions of the country, principally low-class hotels. However, other places especially attractive to tourists continued to develop.

Throughout these years, 87% of tourism was generated by the American market. Las Vegas (which was founded in 1946), Havana, and Miami (to a lesser degree) made up the gambling triangle (Villalba, 1993).

A tour of Havana in the late 1950s would show, especially at night, the great casinos, luxurious hotels and fabulous advertisements up in lights that were symbols of a city of great attractions. Its majestic tourist facilities gave the appearance of development in full swing.

The development of tourism took a different course with a new era starting in 1959 following the triumph of the revolution. The casinos and illegal businesses were closed. The flows of international tourists fell drastically as a consequence of worsening relations with the United States.

Following continued alerts and recommendations to American citizens not to travel to the island due to a supposedly violent and subversive state, administrative measures were taken starting in 1960. One was to prohibit the use of a U.S. passport to travel to Cuba, requiring a special passport and license. Later measures prohibited spending money in Cuba.

International tourist flows decreased from 272,000 in 1957 to 87,000 in 1960. Due to pressure from Washington, the organizers of Canadian trips shut down their operations in the Cuban market. Under similar situations, the French, Germans, British, and Belgians did the same shortly thereafter. Later on the Spanish canceled their operations as well (Salinas y Mundet, 2018).

In these circumstances, the Mexican government undertook to push for the development and creation of tourist centers in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean in order to exploit the new tourist market niche of sun and sand in Mexico. In doing so, Mexico developed a new offering to the North American tourist market in the Mexican Caribbean (FONATUR, 1988).

The closing of the tourist and recreational centers in Cuba following the triumph of the Revolution, and the breakdown of relations with the United States, could have awaken the interest in attracting the North American tourist flow to Mexico. “Following the disappearance of Cuba from the tourist map, a group of islands pushed to fill the void. The Bahamas, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, the Virgin Islands, and even smaller centers like Martinique, Guadeloupe, Saint George or Aruba competed for a tourist flow that reaching four million visitors a year” (FONATUR, 1988:20).

In this setting the tourist center of Cancún, in the Mexican Caribbean, surged ahead. In 1975 it had 1,322 rooms distributed across 15 hotels and received 27,300 foreign tourists, primarily from the United States. In 2000 its infrastructure counted 142 hotels 25,434 with rooms, receiving 2,254,600 foreign tourists.

By the 1980s the Canadian tourist market—the nearest origination market—found it favorable to travel to Cuba. Various tour operators introduced some Cuban destinations in their catalogues with attractive vacation programs, chartering flights for the trips. In this period, and following the election of James Carter as president, the prohibition of travel to Cuba was loosened. New chartered flights started up and docks for small tourist cruises were built, among these a “Jazz Cruise” on board the M.S. Daphne, which had an itinerary between New Orleans and Cuba (Honey y Cols, 2018).

The 1990s presented new contingencies, marked by the collapse of socialism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, on which Cuba was economically and commercially dependent. In response to the internal crisis, the U.S. strengthened economic, commercial, and financial embargo laws.

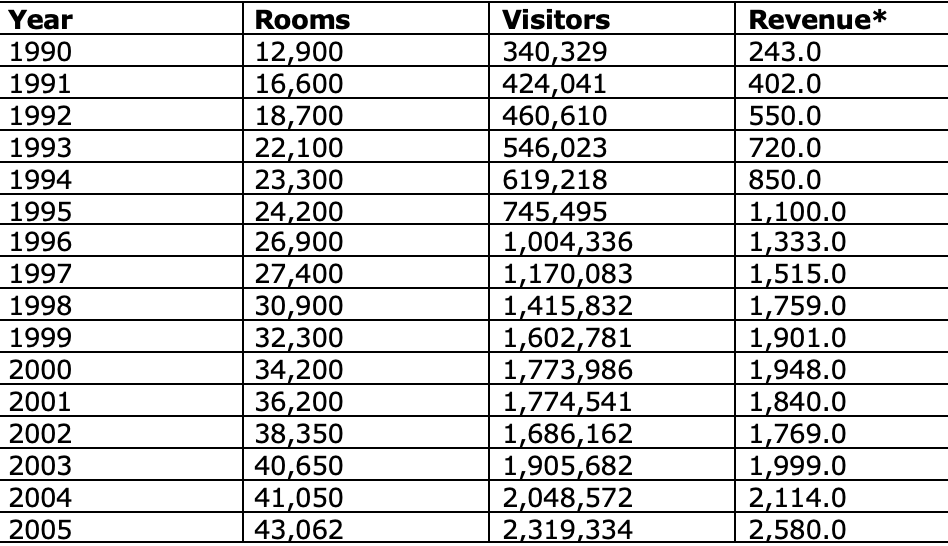

The complex and adverse situation described above suggested that the successful development of international tourism in Cuba was impossible. However, contrary to all of the prognoses, in 1990 Cuba began a new era in this sector. That year Cuba received 300,000 international tourists (Table 2).

In order to provide the necessary capital for investment and to ensure a constant influx of tourists, Cuba welcomed European hotel chains to form associations with national hotel groups. Prominent hotel chains such as Meliá and Iberostar were invited to enter into joint ventures and to administer hotels and vacation complexes.

Tourist visits reached 745,000 in 1995, and by 2005 the number of new visitors had reached 2.3 million. The income from tourism increased to about 2,300 million dollars. (Table 2)

Table 2. Rooms, Foreign Visitors and Revenue Associated with Tourism (1990-2005)

Source: National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI)

Note: *Revenue in millions of dollars.

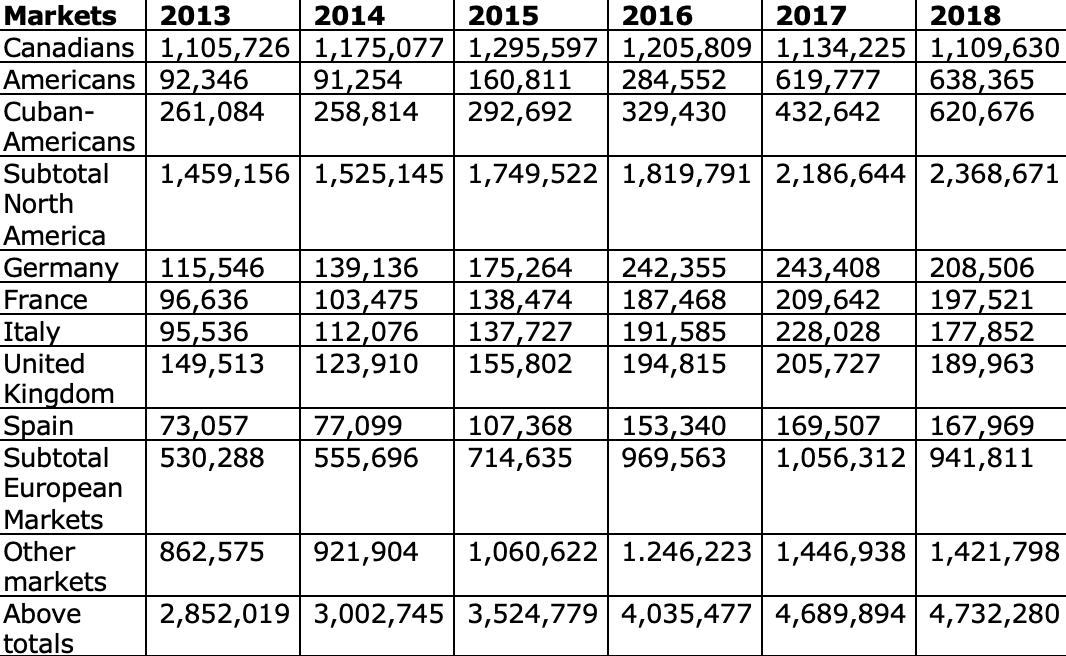

Since the beginning of the 1990s, Canadian tourism has maintained notable growth (Table 3), which has provoked a marked seasonality and polarize of demand focused on all-inclusive, sun-and-sand tourism. Corresponding to this phenomenon, the tourist policy is directed at the beaches, in the commercialization of both tourist packages and hotel infrastructure.

In the last few years in the United States, business interests have developed that make themselves felt in the Congress. Some of these initiatives could end up materializing.

Starting in 2013, the Cuban Government’s National Plan of Economic and Social Development until 2030 recognizes that tourism has a fundament role in the future of the country. It has been considered a strategic sector and the construction of new hotels and vacation complexes in coastal areas and in various urban areas that are sufficiently appealing to attract new segments of international tourism. For Cuba, no other sector could unleash the economic expansion and generate a departure from agriculture and industry like tourism could. However, before that, a profound revision of governmental economic policies is required. Although that is currently underway, they will still take time and require adaptation to the changing times.

The period of rapprochement between the United States and Cuba, which started in December 2014 when the Obama administration resumed diplomatic relations with the opening of embassies in Cuba and Washington, allowed for the loosening of travel restrictions to the island. This translated into a growing flow of visitors and brought many travelers from other originating markets—Europeans more than anyone else (Table 3). In this period, commercial flights started directed from the United States. The principal American cruise lines introduced itineraries to various Cuban ports.

Table 3. Arrivals of International Visitors to Cuba (2013-2018)

Source: Author’s own analysis of data from the Ministry of Tourism (2018a).

During this last five years, international tourism has kept a steady rhythm with an average annual rate of growth of 13%, despite the deterioration of the primarily urban hotels and the difficulties of importing goods dedicated to maintaining them.

Another characteristic that has been observed relates to the concentration of tourism from a select few origin markets. North America makes up almost half of the arrivals to Cuba, but still less than half of the average in the Caribbean.

On several occasions various experts and commentators in the press have suggested that Cuba’s entrance into the sub-regional tourist scene will negatively impact the economy and tourism of independent Caribbean states. However, to see both Cuba’s entrance into the Caribbean system and the normalization of relations with the United States as a threat is, simply put, a geostrategic aberration from certain political and commercial power centers.(Perelló 2017a)

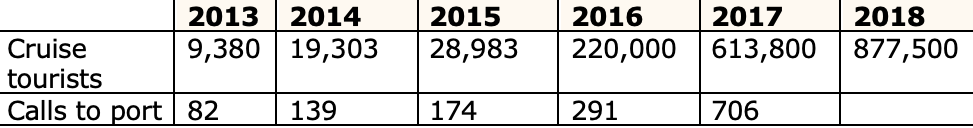

In this scenario, the current Republican administration—despite announcing the reversal of many of the Obama administration’s measures regarding travel to Cuba—has specifically excluded cruise tours. One must take into account American tourists’ growing interest in visiting Cuba and the security that doing so on a cruise (so as not to violate the established regulations), as well as the variety of ports of call that the Cuban archipelago offers (which is superior to any other destination in the region).

In recent years, the arrival of visitors on cruise ships has grown quite significantly (Table 4). In 2013, 9,000 visitors arrived on cruise ships (including crew), while in 2018 there were 877,000; that is, a growth of 43% from the year before. In 2017, 23 cruise lines made 706 calls to 9 Cuban destinations; of those, 304 were in Havana, 145 in Cienfuegos, and 104 in Santiago de Cuba (the principal ports in the country).

Table 4. Cruise Tourist Arrivals and Calls to Port (2013-2018)

Source: Ministry of Tourism (2018a)

The number of cruise tourists form the United States has grown at a high rate: from 171,302 in 2017 to 341,005 in 2018. This demonstrates their interest in Cuba as a destination.

In the last five years, the gradual implementation of an accelerated policy for tourist development, motivated by the updating of the Cuban economic model, has stimulated new investments and the arrival of international hotel companies.

At the close of 2018 Cuba had 69,994 physical hotel rooms distributed in all of the areas of tourist interest. The principal national hotel chains—Gaviota, Gran Carina, Cubanacán, and Islazul—hold 98.4% of the rooms (MINTUR, 2018). In addition to this capacity there are 24,400 rooms in private accommodations (Bed & Breakfast) present throughout the country and which provide an offering complementary to the hotel sector.

With the implementation of a new legal framework for foreign investment and the joint ventures with international hotel chains, agreements have been signed and 13 mixed enterprises have been formed. These enterprises account for 4,995 rooms in hotel facilities and 95 administrative and development contracts with international firms. At the end of 2018, 21 international hotel chains manage 45,333 rooms—of the 69,994 in the country—in 124 facilities under administration and development contracts. These represent 64% of all of hotel rooms (MINTUR, 2018).

Moreover, four mixed enterprises for the development of golf facilities have been created: El Salado, in the Mariel Special Zone; Punt Colorada, in the province of Pinar del Río; Bellomonte S.A., in Havana; and in Matanzas the mixed enterprise Carbonera S.A. The construction of a more than 2400-acre complex which would feature six luxury and high luxury hotels, five golf courses, close to 3,400 villas and 10,000 apartments. Additionally, there would be a port with capacity for 400 mega yachts, shopping and recreational centers, and an equestrian center, among other facilities.

Following the recent conclusion of the National Plan for Territorial Land Use (ENOT) and the updating of the legal framework for environmental protection and adaptation to climate change, the National Plan for Tourism Development until 2030 contemplates 176 projects with different pathways for foreign investment (MINTUR, 2018). Among these, 30 spots for the construction of new hotel resorts in the form of mixed enterprises, 125 hotel administration and development contracts in new and existing facilities, 17 contracts for the administration of services—which includes recreational centers, theme parks, international marinas and nautical services—and four International Economic Association contracts for productive services related to tourism.

Declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1982, Havana has rehabilitated its cosmopolitan image, following the tourism development plan. New opportunities are appearing for the development of the capital city as a dynamic center for the growth of international tourism. This development is under a new strategy directed to market segments with larger vacation budgets and motivations for tourism distinct from the conventional sun-and-sand.

At the end of 2017 the capital had 12,116 physical rooms belonging to state entities. On top of this base, there were 11,552 rooms in so-called “casas particulares” (“private houses”) in the private sector.

Currently there is an accelerated development in the construction and remodeling of five-star or superior hotels, pursuant to management contracts with international hotel chains. Among these investments is the opening of the Gran Hotel Manzana Kempinsky, a facility of the highest standard of 246 rooms, the five-star hotel Packard, with 321 rooms and administered by Iberostar Hotels, and the Sofitel Paseo del Prado, with 264 rooms and operated by the French company Accor.

The policies of the United States toward Cuba could give greater attention to the evolution of changes and the process of modernizing the economic and social model, a task which would in turn create a better understanding of the new and changing economy, as well as what these political-economic reforms can mean to the national interest of the United States. The Executive Branch and Congress should take advantage of the reform process as a unique opportunity of détente for commerce and the economy in the benefit of U.S. citizens.

The new chapter in the development tourist activity will lead from a traditional model of hotel development and a policy of oligopoly towards a new active and inclusive model that emphasizes a policy that corresponds to the diversification of supply to a new demand, and its authentication in a coherent relationship with the national cultural identity of tourist products, both as a whole and in the numerous components both public and private. We need to craft a comprehensive tourism policy—and not just have a collection of isolated traditional products.

Note: The original version of this article was published prior to the recent U.S. regulatory changes eliminating cruise ship travel to Cuba.

References

FONATUR - Fondo Nacional de Fomento al Turismo (1988). Una estrategia mexicana de desarrollo. Memorias sobre la creación de cinco centros turísticos integrales: la huella de Fonatur en la geografía nacional. México DF: FONATUR.

Honey, Martha, José L. Perelló, Jannelle Wilkins y Rafael Betancourt (2018). Por el Mar de Las Antillas. 50 años de turismo de cruceros en el Caribe. La Habana: Ediciones Temas.

Ministerio de Turismo (2017). Cartera de Oportunidades para la Inversión Extranjera. Documento de Trabajo. Edición noviembre. La Habana: MINTUR.

Ministerio de Turismo (2018). Plan Nacional de Desarrollo Turístico 2030. Documento de Trabajo. Dirección de Desarrollo. La Habana: MINTUR.

Ministerio de Turismo (2018a). Desempeño del turismo internacional en Cuba. Series 2013-2017. Documento Interno de Trabajo. Dirección Comercial. La Habana: MINTUR.

Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información (2017). Series Estadísticas de Cuba 1985–2015. La Habana: ONEI.

Perelló, José L. (2016). “Desarrollo del turismo en Cuba: tendencias, políticas e impactos futuros”. En Cuba in Transition. Proceeding Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy, vol. 26 (pp: 229-233). Washington DC: ASCE.

Salinas, Eros y Mundet, Lluis (2018). “Historical Evolution and Spatial Development of Tourism in Cuba, 1919-2017: What Is Next?”. Tourism Planning & Development 15(3): 216-238.

Spadoni, Paolo y José Luis Perelló (2018). The Cuban Tourism Industry: Evolution, Challenges, and Prospects. Book Manuscript. Manuscrito presentado para publicación.

Villalba Garrido, Evaristo (1993). Cuba y el turismo. La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

José Luis Perelló Cabrera, Doctor en Ciencias Económicas, es Profesor Titular de la Facultad de Turismo de La Universidad de La Habana. Miembro de la Cátedra de Estudios del Caribe. Máster en Gestión Turística por la Universidad de La Habana y MBA en Alta Dirección de Empresas Turísticas por la ESADE de Barcelona. Ha participado como profesor invitado en Universidades de Estados Unidos, Centro y Suramérica. Ha publicado varios libros y artículos en revistas especializadas nacionales y extranjeras, y en medios de comunicación de varios países. Se especializa en temas de migraciones internacionales y desarrollo turístico.

JLPC Tourism (En) (ed) + Access.pdf 151.45 KB