The Cuban Diaspora’s Increasing Role in the Context of Changes on the Island

Cuban immigrants, primarily from Florida, are connecting with the island and sharing new ideas, through creative methods of remittance, by investing in businesses, and in organizing and delivering humanitarian aid.

By Denisse Delgado Vázquez

University of Massachusetts, Boston

There’s a store in Miami where you can buy school uniforms for Cubans on the island—the exact same design, although not the same fabric. I’ve even run into a friend there. People buy the uniforms and send them to Cuba—a sort of material remittance.

The Cuban school uniforms are actually manufactured in Hialeah, a city on the outskirts of Miami, known for its commercial activities in Havana. The store, Ñó, qué barato (which means “wow, this is cheap!), has been promoted as “a store in Miami to alleviate the shortages in Cuba.” (VoaNoticias, January 22, 2019). From the store, my friend called his ex-wife in Cuba to get the size of his son's school uniform pants. The child is too tall for uniforms sold on the island. Although local uniforms do not fit him, he is required to wear the uniform in any case.

My friend is content that he can buy these pants in Miami so his child will not be scolded by any teacher or the school director in Cuba. This is a good example of transnationalism: the use of technology (the phone and WhatsApp) in maintaining economic and cultural ties, across national borders.

In my doctoral work—as well as in the posts I provide as one of the principal contributors to the Cuba Capacity Building Project at Columbia Law School, Horizonte Cubano (Cuban Horizon), I am investigating the use of remittances in the emerging non-state sector of Cuba’s economy by taking a deep look at Miami’s connections with the island. Miami is only 90 miles from Cuba; and this logically favors Cuban migration to Florida. Moreover, Florida is the home of the largest Cuban community living abroad. Overall, it is estimated that there are about 2.4 million Cubans living abroad (U.S. Census, 2017), and 1.5 million of them live in Florida. This represents about 62.5% of the total of Cuban migrants. (DACCRE Directorate of Consular Affairs and Cubans Residing Abroad).

Innovation and Fomenting New Ideas

There’s a lot of innovation going on as the younger generations of the Cuban diaspora, those who migrated after 1995, as well as second and third generations of immigrants before them, have been increasingly able to maintain ties with the island. Sending remittances, investing in businesses, helping out in natural disasters, visiting, exchanging ideas and teaching what they have learnt from their experiences in the United States are new ways of interacting—quite different from the relations of the exiles who fled the island after the Cuban Revolution and were not permitted by the Cuban government to return.

Today, ties between Miami and Cuba are more intense, frequent, and multifaceted due to the use of cell phones (many of which are financed with by “top-ups” – refilling phones in Cuba by relatives and friends in Miami), and by the use of mobile messages, email, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, chats, forums, and other virtual platforms. These platforms break the barriers of communication which were created by physical distance and restrictive policies both governments imposed in the past.

The transmission of new ideas and knowledge also intertwines with innovation. A few months ago, I had a conversation with a friend, who is a computer engineer. He lives in the United States, where he works as a webmaster, and at home he has a machine he uses to “mine” Bitcoins, a digital currency. He adds to the blockchain technology that is part of the international network and is rewarded in Bitcoins.

As part of this venture, my friend has created a software application through which he and his cousin in Cuba refill the cell phones of Cuban customers online using Bitcoins. While his cousin in Cuba is paid in Cuban Convertible Pesos (CUC - the Cuban hard currency) by Cuban residents to refill their phones, my friend in the US uses his Bitcoin balance to accomplish the refill transaction. In this way, Bitcoins have become acceptable currency to pay for cell phone service in Cuba. The profits generated by this venture stay in Cuba. They are shared with his cousin and a portion is used to support my friend’s family in Cuba. Perhaps because of the economic shortages, Cubans have been creative in solving their needs.

This innovative solution has various outcomes.

- First, those who do not have family living abroad to send hard currency to pay for their cell phone usage can refill their cellphone data using this mechanism.

- Second, other people living abroad who have access to them, may use Bitcoins to support their family’s cellphone use in Cuba. By this method, they are providing economic support to their relatives in Cuba from abroad.

- Third, since this form of aid does not go through Western Union—the means through which cash is traditionally sent — it therefore incurs no taxes or service fees. Moreover, cash does not have to be transmitted using mulas, the people who go back and forth from Miami to Cuba to transport goods and money.

- Fourth, by creating the application and using it in Cuba, he is transmitting new knowledge to family members living in Cuba: he teaches them how to use new technologies to earn money and use the profits as working capital for an enterprise.

- Fifth, he teaches his cousin the concept of investment: "even if you have little money, you risk it by investing, and you get it back as a return on your investment," my friend said.

- Sixth, he also teaches his relatives the concept of credit (to which few have access in Cuba) when he loans money to his cousin for other products, with the understanding that it should be returned.

All this works in a transnational and virtual space, where there are economic actors operating in the same economic dynamic but from different geographies.

Connecting Through Humanitarian Aid

Another area of connection between sociocultural and economic remittances and help is through the humanitarian aid some groups have offered to people living on the island. A tornado hit Havana January 27, 2019 — a totally unexpected natural disaster that destroyed communities, affecting countless families.

Well-known organizations such as Friends of Caritas Cuba (Boston) set up their website to send monetary help and support the affected communities in Havana. In addition to the quick response of such organized support groups, many Cubans living abroad joined forces to collect, pack, and send aid. There were members of the diaspora who contacted private businesses to solicit contributions, and they took them to the affected communities. Both Cubans living abroad and entrepreneurs living in Cuba used social networks (such as Facebook and WhatsApp) to organize themselves at a surprising speed. This demonstrated the agency and capacity of both groups of actors to generate a coordinated effort to positively impact people's lives. Unlike in the past, they did not wait for the government’s guidance about what to do and when.

Cultural Identification by the New Generations

Another area of connection is music, fashion and slang, which are continuously exchanged by the two geographies. It is easy see how similarly the youth dress when they go out in Miami and in Havana. I notice the difference from the way youth dress in Boston, even during the summer. Similarly, the music that is heard and the slang that is used confirms there is a continuous channel of communication in which people from both sides update their vocabulary and ways of speaking.

According to the 2018 Florida International University Cuba Poll, Cubans are more willing to engage with Cuba, especially those in the younger generations, specifically, those who arrived after 1995, or the second and third generations after the Revolution. (Cuba Poll, 2018: 4) Those who migrated after 1995 were mainly motivated by economic reasons rather than political ones, and the second and third generations might think about Cuba and migration as something from the past - experiences that relate more directly to their parents and grandparents

With the Obama administration's liberal travel policy, trips to the island grew exponentially. Cruises began arriving in Cuba from the United States. Thus, in 2018, more than 521,000 Cubans residing in the United States visited the island. From January 1 to April 30, 2019, more Americans arrived on cruise ships (142,721) than visitors by plane (114,832), according to an article published by OnCuba News (June 6, 2019). The United States was the second largest source of visitors to Cuba until April of that year, and cruise travel had grown by 48%, compared to the previous year (Ministry of Tourism of Cuba, Agencia EFE).

Cubans on the island quickly adjusted to the new dynamics and the possibility of launching private ventures to sell services to those visitors. They were also able to take advantage of the benefits of serving American and Cuban-American tourists, who are also highly appreciated for their culture of leaving tips. These tips especially favor those who work “the front of the house” offering their services.

Visits to Cuba meant being able to know a reality not told or distorted by the mass media. Americans and Cuban-Americans also transmitted to people in Cuba their own reality which has more nuances than what the Cuban mass media shows on the island. It was an opportunity for mutual recognition and rediscovery.

Data (Cuba Poll 2018) supports the change in the experience of Cuban- Americans’. Now, 57% of respondents support unrestricted travel for all Americans to Cuba. The majority of Cuban-Americans in Miami-Dade County (68%) support the expansion or maintenance of business relations with Cuba by U.S. companies. Newcomers are poorer than those from previous migratory waves, as well as racially more diverse, and younger; and they are more willing to support policies of rapprochement with Cuba. They seem to be the most conciliatory voices.

Sending Remittances to Finance Private Businesses

Remittances sent by the Cuban diaspora in previous times were mainly used to cover basic household needs such as food, clothing and housing, although they also helped subsidize the development of small private restaurants known as paladares.

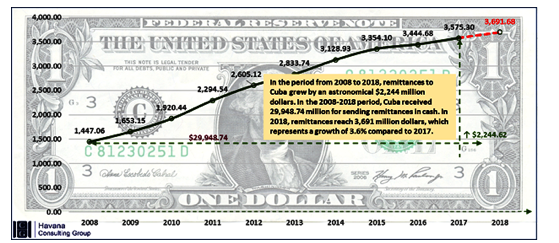

Havana Consulting Group, Miami, Florida 2019 [i]

However, in 2011, the Cuban government introduced a set of economic reforms to relaunch the private sector. The development of small and medium private enterprises in Cuba shows an increasing incorporation of workers in the private sector. Before 2010, the figure was around 157,000, and by September 2019 there were 617,974. This represents 13% of all Cuban workers, according to the Cuban Ministry of Labor and Social Security. To the extent that the number of self-employed people has grown, remittances have also increased, many of which are destined for the development of these same private initiatives (According to the Miami-based Havana Consulting Group, $3.6 billion in remittances were sent to Cuba in 2017).

Now, in addition to helping with basic necessities, remittances are being used as working capital for the development of private initiatives improving the economic situation of relatives, friends, neighbors or receiving partners.

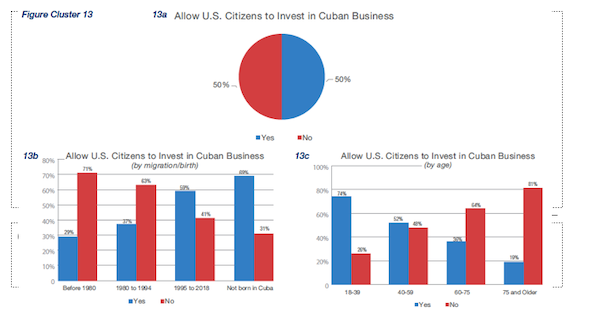

Allow U.S. Citizens to Invest in Cuban Businesses [ii]

The Cuba Poll (FIU, 2018) also suggests that a considerable part of the diaspora values investment in Cuba as a possibility. If allowed, half of the respondents would invest in small businesses in Cuba. Especially the most recent cohorts, that is, those between 18 and 39 years old. (After 1995, 58.6% of this group expresses support for investing). Sixty-nine percent (69%) of respondents who were not born on the island also support the opening of investment opportunities. Of these Cuban-Americans that support investments in Cuba, 46% would invest in their own private company in Cuba. But those who arrived before 1980 respond with an almost resounding "no" to making a personal investment on the island (66%), which marks a generational difference.

Investments in private initiatives in Cuba have a significant impact, as they generate jobs and help entrepreneurs get out of poverty. When I interviewed Cuban economist Omar Everleny Pérez in 2017, he told me:

"Unlike the Mexicans who go to work in the United States and send remittances to support their family, in the Cuban case it has been mixed. On the one hand, the Cuban diaspora has not been allowed to make banking investments in Cuba due to the limitations applied by both the governments of Cuba and the United States. On the other hand, they send larger amounts of remittances to contribute to the development of private businesses owned by their friends and relatives on the island”.

As money cannot be invested from the United States to Cuba by means of bank transfers, they send remittances in cash. In one shipment they may send US $5,000 and later on they send another for US$ 4,000.” (Delgado, 2017). This is significant as it marks differences between the Cuban and other Latin American diaspora regarding their economic participation in their country of origin.

The Fluidity of Sociocultural Remittances

Cultural, social or socio-cultural remittances is another nontraditional concept, which has been used to explain the transmission of new ideas, practices and identities, concepts, knowledge and values between different territories. Cultural remittances refer to expressions of culture that travel and are altered due to the exchange of languages, music, literature, painting and other artistic genres. In my research approach to South Florida during the summer, I witnessed the naming of a street in honor of the Cuban singer and songwriter Carlos Oliva. I was also able to appreciate the 22 Cuban paintings that grace the outer walls of the historic public library in Hialeah. The appreciation for the Cuban music and art evidence the importance of the cultural aspects of identity across seas.

The transmission of new sociocultural ideas and values also happens at the family-level between those who live in Miami and Havana. Attitudes such as focusing on individual needs rather than collective needs, being totally independent and self-sufficient, and recognizing your own merits are usually considered in Cuba to be a show of arrogance or a lack of modesty. Yet, family members living in the United States understand these are important values and positive entrepreneurial skills. While these are new values or cultural ideas learned by the Cuban diaspora in the US, some members enhance the importance of those values to their friends and family in Cuba during family visits.

International migration is a complex and dynamic phenomenon. Immigrants throughout history have moved from their country of origin motivated by diverse factors. In the case of Cuba, new migration has meant the possibility of new interconnections—both cultural and entrepreneurial.

A version of this article was previously published in ReVista, Harvard Review of Latin America

i] This image of a dollar sign shows the steady increase in remittances to Cuba. During the period of 2000-2018, remittances to Cuba totaled US$30 billion, steadily increasing from US$1.5 billion per year in 2010 to US$3.7 billion in 2018.

[ii] The chart above shows two sets of columns, each with the blue columns depicting those who favor investment in Cuba and red columns showing those who oppose it. The first set of columns presents the data by migration date: before 1980, between 1980 and 1994 and between 1994 and 2018, and finally those not born in Cuba. The second set of columns presents the data by age group, 15-39, 40-59, 60-75 and over age 75.