What Effects Do U.S. Sanctions Have on the Cuban Economy?

The Cuban government has found ways to reorient international alliances, manage fiscal budgets, and regulate the economy to minimize the impact of sanctions on its businesses and priority projects.

This article is based on a more detailed one recently published in the Journal of International Development, which examines the economic effects of past changes in U.S. sanctions policy against Cuba.

Economic sanctions are defined as actions taken by one or more countries to limit or end economic relations with a target country to influence policy changes or achieve regime change. The latter has been the aim of the sanctions imposed by the U.S. government on the Cuban economy since the 1960s.

Sanctions can take many forms: tariffs, export controls, embargoes, import bans, travel bans, asset freezes, aid cuts, blockades, or restrictions on specific companies and individuals.

Most international studies find that sanctions negatively impact the GDP growth rate, foreign investment flows, and financial stability of the sanctioned country. The effects vary depending on the size and interdependence of the countries involved, whether the sanctions are unilateral or multilateral, and the extent of the sanctions—whether they are targeted at specific industries, companies, or groups of citizens or whether they are broader, general sanctions like those imposed on the Cuban economy.

While there are arguments in support U.S. sanctions on Cuba from a variety of quarters, there is wide agreement among scholars that it is a failed policy. The arguments supporting this view come from diverse perspectives, whether focusing on the internal political impacts, foreign policy consequences, or the legitimacy and effectiveness of sanctions in defending human rights.

As to economic impact, some authors highlight their ineffectiveness in isolating Cuba economically. Others stress that sanctions mainly affect families without leading to regime change or promoting democracy in Cuba.

At the beginning of 2025, with the transition from the Biden administration to the Trump administration, the subject of sanctions on the Cuban economy has once again made headlines. In his final days in office, President Biden notified Congress of his decision to remove Cuba from the list of state sponsors of terrorism, a move facilitated by Vatican mediation and aimed at securing the release of 553 political prisoners.

Moreover, Biden suspended the enforcement of Title III of the Helms-Burton Act for six months, which had allowed U.S. citizens to file lawsuits in American courts against third parties using expropriated properties in Cuba. Furthermore, the president rescinded a 2017 memorandum prohibiting U.S. citizens, companies, and entities from conducting financial or commercial transactions with a specific list of Cuban businesses and organizations.

However, on his first day in office, President Trump reinstated Cuba on the list of state sponsors of terrorism. With the confirmation of Marco Rubio as Secretary of State—known for his radical stance against the Cuban government—many analysts anticipate that the new administration will implement stricter sanctions on the island and increase diplomatic confrontation with Havana.

An Econometric Analysis of the Data

A recent study published in the Journal of International Development[i] examined the economic effects of past changes in U.S. sanctions policy toward Cuba. An econometric analysis was conducted using historical data from the 1990s onward. The study analyzed how fluctuations (increases/decreases) in trade flows, remittances, and visitors from the U.S. impacted the Cuban economy.

During the study period, the most significant easing of sanctions occurred under President Obama. Restrictions on Cuban-American travel and remittances were lifted, and aviation companies were allowed to initiate regular commercial flights to the island.

Postal service between the two countries—suspended since 1960—was restored, and government dialogues resumed in various areas. Financial restrictions were relaxed as Cuba was removed from the list of state sponsors of terrorism, allowing the use of the U.S. dollar for authorized transactions and enabling American banks to process transactions between Cuban and third-country banks.

During Donald Trump's administration (2017–2020), another shift in policy occurred. Individual visits were suspended, cruises were canceled, commercial flights were restricted, and U.S. citizens could only travel in groups licensed by the Treasury Department. They were also prohibited from staying in or patronizing an extensive list of state-owned hotels, restaurants, and businesses. Remittances were once again limited, and Cuba was reinstated on the list of state sponsors of terrorism. The State Department created a list of Cuban companies—mainly hotels and agencies controlled by military, intelligence, and security services—with which financial transactions from the U.S. were prohibited.

President Trump activated Titles III and IV of the Helms-Burton Act—breaking with the tradition of previous U.S. presidents—allowing lawsuits against third-country entities benefiting from commercial activity with any of Cuba's nationalized assets.

The econometric study also examined the effects of policy shifts during the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations. The empirical strategy measured, over the period of three decades, the sensitivity of Cuban economic growth and other macroeconomic indicators to sanctions shifts (tightening/easing). In addition to estimating the impact on GDP growth, the study differentiated the impacts of the policies on state and private sector economic actors.

The econometric estimates used a Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model, widely applied in finance, macroeconomics, and international economics for its ability to analyze datasets without imposing excessive theoretical constraints. VAR models consider potential feedback effects (temporal interdependence) and time lags between variables.

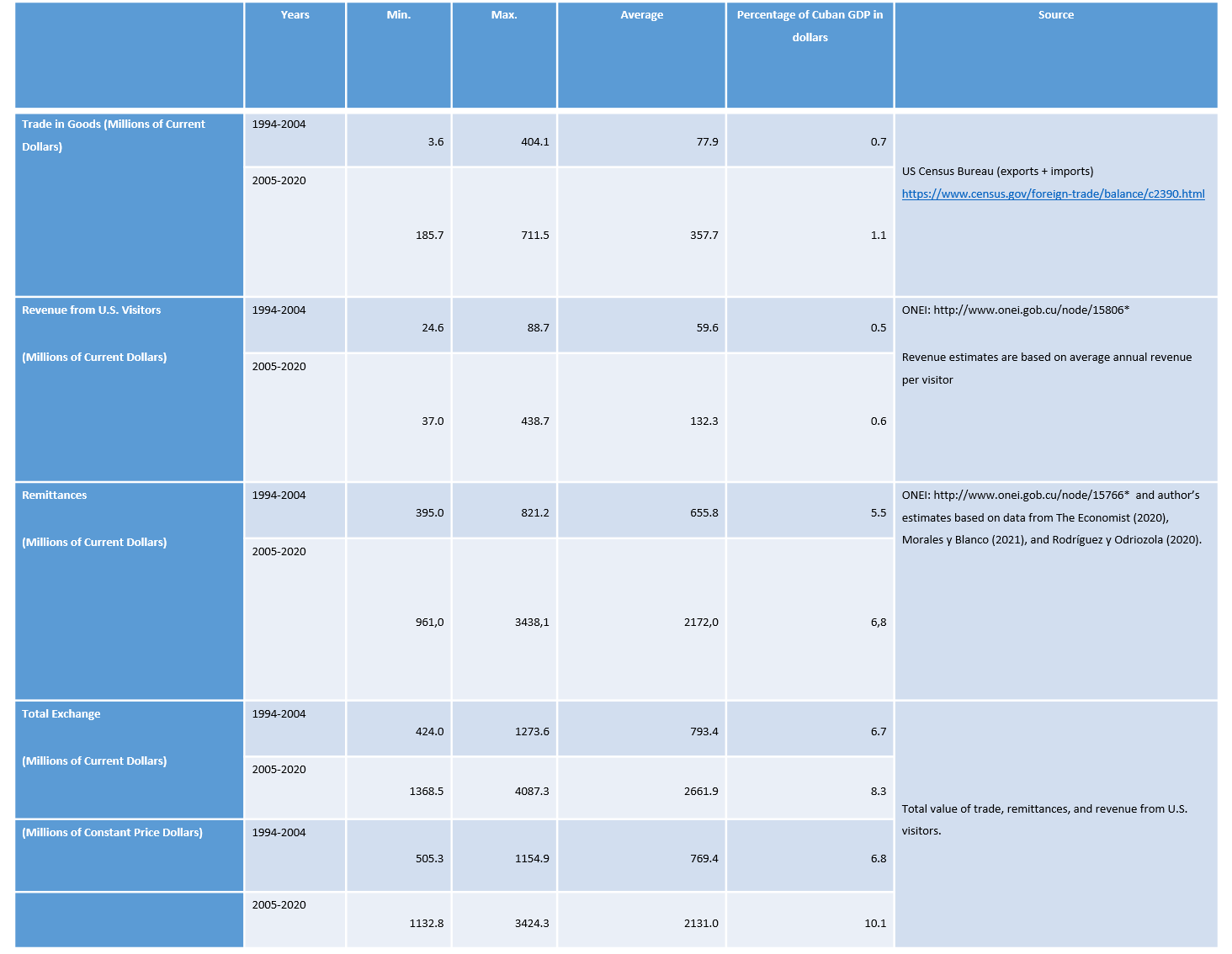

Before estimating the model, it was necessary to reconstruct the database of exchange flows between the United States and Cuba from the 1990s, covering trade in goods, remittances, and travel. Table 1 below provides a summary of the database and the sources consulted.

The data show, for example, that exchanges with the United States accounted for an average of 8.3% of Cuba’s GDP between 2005 and 2020, with remittances being the most significant and stable component. Total economic exchange peaked in 2018, exceeding $4 billion. While trade in goods overwhelmingly favored the U.S. economy (accounting for 99.7% of the external trade balance), when considering revenue from remittances and visitors from the United States, Cuba achieved a significant surplus in total economic exchange.

Table 1: Cuba-U.S. Trade, Visitors, and Remittance Statistics, 1994-2020.

*Due to difficulties with the external validation of the site, it is not operational outside of Cuba.

Source: Vidal, P. (2024). Impact of Sanctions Policy Shifts: A Case Study of the United States and Cuba, 1994–2020. Journal of International Development .

The VAR model showed that Cuba’s GDP growth was most sensitive to fluctuations in exchanges with the United States. The second most sensitive indicator was consumption in private markets. Government spending and household consumption showed similar effects, although in the case of the former they were not statistically significant, but they were in the latter.

The historical series analysis found that remittances from the United States have significantly influenced consumption in Cuba’s private markets but have not had a significant impact on Cuban government consumption.

Another notable finding of the VAR model is the positive and significant impact of total exports (a control variable) on GDP growth and government consumption. These do not solely depend on the sanctions framework but on factors related to economic competitiveness and efficiency, as well as alternative international alliances that the Cuban government has managed to establish.

In summary, the econometric estimates confirmed the significant impact of shifts in sanctions policy on Cuba’s economic growth. The analysis demonstrates that fluctuations in the flows of goods, U.S. visitor revenue, and remittances from the United States significantly influenced the trajectory of Cuba’s GDP. The study highlights the vulnerability of Cuban families and the private sector to changes in sanctions policies.

While the econometric results confirm the economic impact of sanctions, they do not justify the Cuban government’s exclusive attribution of the country’s economic difficulties to the embargo. There are internal barriers that clearly limit the economy’s competitiveness, its ability to fully integrate into the global economy, and its capacity to expand exports.

Findings and Policy Implications

The article provides statistical evidence that contributes to the debate on the economic benefits of relaxing sanctions and the impacts of tightening them.

However, it is important to clarify that the estimations do not seek to approximate the total cost of the sanctions. Nor do they attempt to assess the full benefit that the future lifting of all sanctions could bring to the Cuban economy. Due to the multiple areas and channels through which sanctions restrict trade, finance, investment, and economic growth, determining a total cost for the sanctions is exceptionally complex.

While the estimations offer valuable insights into the consequences of partial changes in the regulatory framework accompanying the sanctions (using historical data since 1990), they do not attempt to determine how the Cuban economy would fare in a hypothetical scenario without sanctions.

Without a clear counterfactual, measuring the true impact of the sanctions is inherently difficult. Although U.S. sanctions have not succeeded in altering Cuba’s political and economic system, it is impossible to determine what would have happened in their absence.

Several factors would need to be considered in a hypothetical scenario without sanctions. The Cuban government's political response and the extent of its reforms would define the trajectory of economic development. If Cuba were to adopt more market-oriented reforms, economic outcomes could be significantly different.

The level of engagement and response from the Cuban community in the United States would also be crucial. Increased investment from this community could provide a substantial boost to the Cuban economy.

Support from multilateral financial institutions and the international community is another key variable that defines access to international financial markets, loans, and assistance, which would facilitate economic reforms and greater openness.

Why is the Cuban Government Less Affected by U.S. Sanctions?

The econometric estimations demonstrate that Cuba’s GDP trajectory has a statistically significant dependence on increases or contractions in the flows of goods, visitors, and remittances from the United States.

The data also suggest that this impact on GDP is concentrated in household consumption and private markets, with no statistically significant effect observed on government spending.

How Can These Results be Explained?

The study suggests that the Cuban government has managed to reorient international alliances, manage fiscal budgets, and regulate the economy to minimize the impact of sanctions on its businesses and priority projects.

Cuba has established trade agreements and investments with Venezuela, China, Brazil, the European Union, Russia, Canada, and Mexico, among others, at different times, serving as an alternative to economic ties with the United States and helping sustain state expenditures and investments.

Cuba's fiscal policy management to mitigate the impact of the sanctions is also evident in historical data. Since the 1990s and in response to increases in sanctions, the government has responded with expansionary fiscal policies, maintaining subsidies and resource transfers to state enterprises and projects of questionable profitability.

In many cases, fiscal deficits have been financed through money issuance by the Central Bank of Cuba. The monetization of fiscal deficits increases the amount of national currency in circulation, increasing inflation, and affecting the convertibility of national currencies (CUP, CUC, and MLC) as well as bank accounts. Thus, one way the Cuban government has transferred the cost of the U.S. sanctions to households is through "inflation taxes" and the devaluation of their savings.

Along with the fiscal deficit, the Cuban government has also employed centralized foreign exchange controls, dual-currency schemes with restricted convertibility, multiple exchange rates, and partial dollarization to sustain the capture and allocation of resources toward its priority projects (such as hotels, to cite a recent example).

The management of regulatory frameworks, the abuse of the monopolistic power of state-owned enterprises, the privileges and lack of transparency of military-run companies, as well as monetary and fiscal policies, have allowed the Cuban government to asymmetrically distribute the impact of sanctions and other external shocks. This is facilitated by a centrally managed economy with limited space for the private sector.

Families and the private sector have very few options to escape the impact of sanctions. Households operate under strict budget constraints, with limited opportunities for private entrepreneurship growth and restricted access to financing. Families are left defenseless against the abuses of public policies in a political system that criminalizes social protests and offers no real spaces for civic participation.

Unlike the government, households have very little capacity to diversify their international relations. Their dependence on financial assistance from the Cuban community and remittances from the United States is high and geographically immovable.

Are Sanctions Solely to Blame?

While the econometric results demonstrate the impact of sanctions on economic growth, they do not support the Cuban government's claim that the country's economic difficulties are entirely due to the embargo.

The econometric estimations published in the Journal of International Development use Cuba's total exports as a control variable, allowing the exclusion of the effects of other economic shocks and policies that have affected the Cuban economy over the past three decades.

The econometric results show that sanctions influence the dynamics of economic growth, but to a similar extent as total exports. Although export dynamics are influenced by various factors, they primarily depend on the competitiveness of the economy.

Competitiveness is affected by monetary and financial instability, defaults on external debt payments, the multiple exchange rate regime, and inefficiencies in the state-owned business sector—among other factors that are more directly related to internal policies and the lack of reforms.

In recent years, the Cuban government has delayed the implementation of a macroeconomic stabilization program and continues to resist deep structural reforms to its centrally managed economic model.

The failure of this model and its economic policies has persisted over time, severely damaging financial confidence and credibility. Even allied governments governments and markets that in the past helped diversify Cuba's international trade and financial relations or circumvent sanctions are negatively impacted by the failed Cuban model.

The prolonged economic crisis of its main regional ally, Venezuela, has worsened this situation, and the Cuban economy has not been able to find an alternative pattern of international integration. The tourism industry no longer shows the dynamism of previous decades. Foreign currency revenues are in free fall.

In this context, especially after 2020, the Cuban government’s ability to circumvent sanctions through the reconfiguration of international alliances appears to have significantly diminished. However, the production structure, power relations, and rent-extraction mechanisms remain in place, leaving Cuban families in an increasingly vulnerable situation in the face of a potential escalation of sanctions under a Trump administration. If we add to this the severity of the actual social crisis in Cuba, we can anticipate devastating humanitarian consequences.