Venture Capital – A Worldwide Phenomenon

Venture capital has produced breathtakingly successful results, creating jobs, developing industries, and nurturing new products and services, and it could ignite the innovation and creativity for which the Cuban people are known.

What is Venture Capital?

Within a societal framework where private capital plays a role in the financing of entrepreneurial enterprises, venture capital has played a very important part in many countries. Venture capital (or “VC”) is capital invested in a project where there is a substantial element of risk, such as a startup enterprise that may or may not succeed. The professional deployment of venture capital has produced breathtakingly successful results, in terms of the creation of jobs, the development of industries, and the nurturing and development of new, innovative products and services, while producing extraordinary wealth that is distributed both to the management and employees of these companies, as well as to the venture capital firms and their investors. Some of many examples of companies that within their industry sectors were initially created with the support of venture capital include the following: Federal Express, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, PayPal, Microsoft, Tesla, Twitter, Genentech, Oracle, Netflix and Uber.

History and Evolution of Venture Capital

The most striking successes in venture capital originated in the United States, but in recent years other countries such as China, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Sweden, Israel, Argentina, Columbia and Brazil can point to outstandingly successful companies created with the help of venture capital.

The United States is widely recognized as the place that launched the venture capital industry. The year 1946 is considered the beginning, when American Research and Development Corporation (“ARDC”) was founded by individuals who invested their own funds and those of outside investors to facilitate the creation of companies by soldiers returning from World War II. ARDC invested in a number of private companies, one of which, Digital Equipment Corporation (“DEC”), a microcomputer company, grew over a period of 14 years to be valued at $355 million. ARDC made an initial investment in DEC of $70,000, representing at the time 77% of the equity of DEC.

Since then, the VC industry has evolved and grown rapidly in the United States. Initially, large public corporations, such as Citicorp (through Citicorp Venture Capital, or “CVC”) and today Intel Corporation and Qualcomm Technologies, Inc., have created venture capital subsidiaries. In addition, very wealthy individuals have allocated a relatively small percentage of their total investment assets (often structured as a family foundation) to venture capital.

However, the industry rapidly evolved into one where private partnerships managed by a handful of individuals (known as “general partners”) dominated the VC. These partnerships use a limited partnership structure whereby the capital is supplied when requested by the limited partnership for a designated investment from capital commitments made by large institutions, such as pension funds, fund of funds (I.e., aggregates of many smaller pension funds), insurance companies, foundations and university endowments, which are the limited partners in the limited partnership structure. The general partners identify the investment opportunities and manage the investments of cash from these limited partners.

The growth of venture capital has been assisted in the U.S. by helpful legislation, such as favorable tax treatment of long-term capital gains and the 1979 pension reform law that increased up to 10% the portion of employee pension fund assets that could be invested in VC funds. The success of the venture capital phenomenon in the U.S. led to the formation in 1973 of an industry trade and lobbying group, based in the nation’s capital, known as the National Venture Capital Association (“NVCA”).

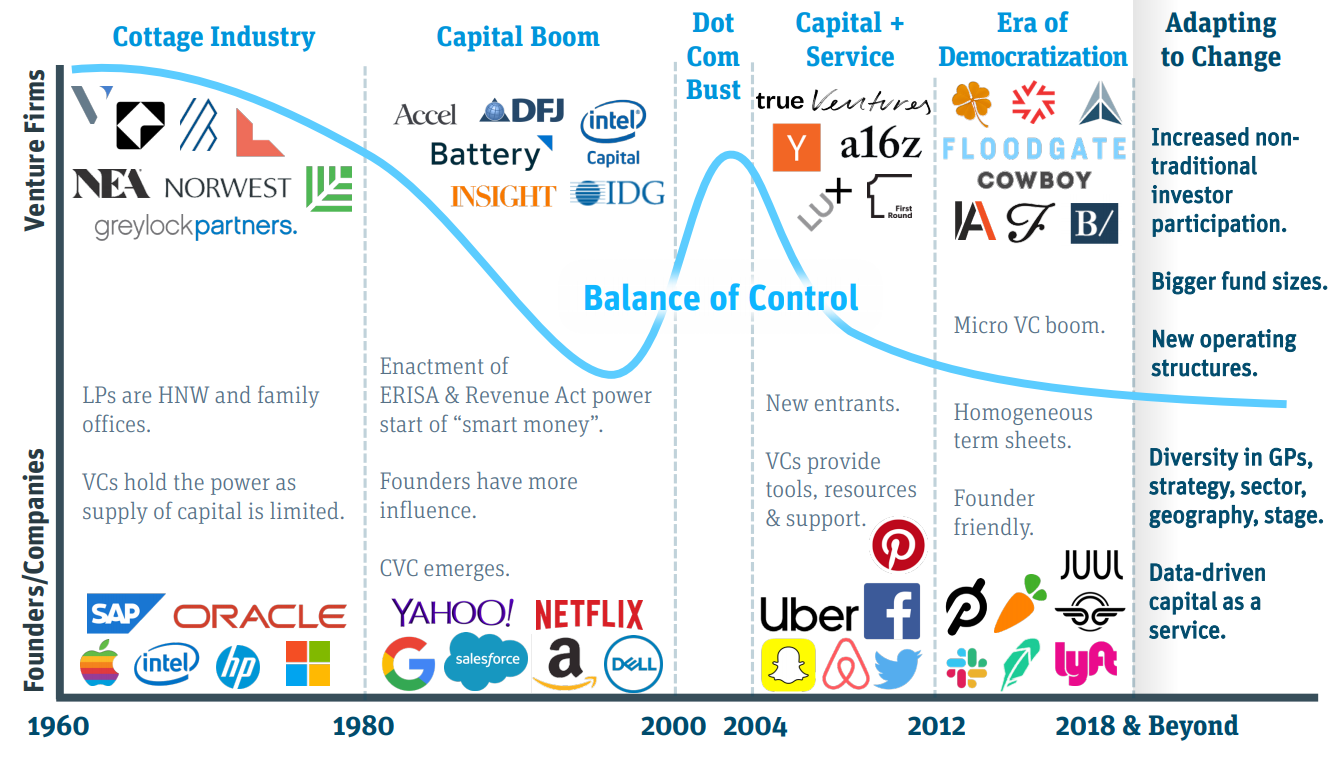

As of 1985, there were more than 290 active VC firms in the U.S., managing more than $17 billion in assets through 530 funds. The VC industry enjoyed a strong stock market from 2000 until early 2020, when the U.S. entered a recession and the global pandemic stemming from COVID-19 surfaced. The industry began 2020 with about 1,300 active firms and $444 billion in assets under management, representing phenomenal growth. A summary of the venture capital evolution is depicted below:

Source: Silicon Valley Bank, Q3 2019 State of the Markets Report

The chart above indicates the phases of the growth of the VC industry over time, as it evolved from an industry sponsored by some pioneering investors, to a cottage industry, to the corporate stage, and eventually growing into major partnerships managing very large sums of money, according to accepted standards of investing. Today, VC partnerships often specialize in a particular development stage of a business, or by industry, or by the type of technology. Venture capital is itself still a relatively small industry, however, with only about 400 firm members of the NVCA, whose general partners total a few thousand individuals.

Why Invest in Venture Capital? – An Institution’s Perspective

A key question for employee pension funds, university endowments, individuals and others investing in venture capital is why do it, if the individual new enterprises are so risky, with many start-ups that do not succeed. Many fail or are acquired by companies at a loss to the original investors. The simple answer is that patience and the rule of numbers under professional investment[i] provide the answer.

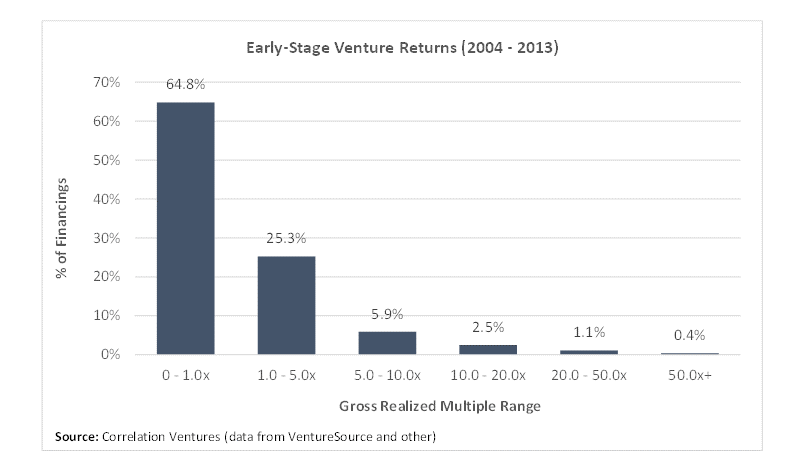

Venture capital is a long-term investment; individual liquidity exits from investments (i.e., when the investment can be converted into cash) can take many years. Time has proven that if such investments are professionally managed by general partners of VC firms, the returns on average from a portfolio of investments can be extremely high, exceeding the returns from investing in publicly traded corporate stocks or many other types of investments. However, returns are heavily influenced by the risk the investment presents. The earlier the stage of investment, the greater the risk, illustrated by the graph below:

This graph shows that the typical loss rate for early-stage investments is 65%. This means that 35% of the early-stage investments must generate gains much greater than 1x to achieve an acceptable overall result.

Why Does an Entrepreneur Seek Venture Capital? – A Founder’s Perspective

Investing money in order to seek a return on investment is a challenge in any society, be it capitalistic or not, because how does one measure the value generated by human activity? In countries where some sort of capital market exists and where the allocation of capital is made according to projected financial benefit, the measure is usually associated with “return on investment”.

Providers of capital are concerned about experiencing losses. Banks, for example, as heavily regulated entities, are sensitive to the potential negative effects on their depositors and are answerable to regulators who evaluate their investment practices. The safety and reputation of the bank will suffer if it makes risky loans or investments. The corollary is that entrepreneurs find it difficult to locate sources of capital to fund a high-risk business idea if most sources of capital regard the proposed enterprise as too precarious. The result is a capital market gap between very safe investments on the one hand and risky but potentially high investment returns on the other.

It is in filling this gap where venture capital plays a crucial role. For the creator of an idea who forms a company and needs to raise money, venture capital may be willing to step in. First, the founder needs to sell the idea to a VC firm. But how to do that successfully, particularly if he or she is unknown and has no prior entrepreneurial success? The answer is it to develop the most persuasive profile on the proposed idea. The greatest chance of success is to write a business plan that addresses the criteria important to the VC firm:

- The idea addresses a potentially a large and fast emerging market – where there is a strong likelihood that consumers or companies will pay for the product or service at prices that allow an attractive gross margin to sustain ultimate profitability.

- The idea will be protected from competition by patents and trademarks or rapid development of a leading market share protected by knowhow and momentum.

- A management team that is assessed by the VC firm as first class; if gaps exist in the management team they are deemed to be easily filled.

- A conclusion is reached by the venture capitalist that, with the right amount of capital raised, the new company will have a key advantage over potential evolving competition.

Assuming that the founder(s) has confidence that he or she has a business plan that meets some or all of the above criteria, the founder(s) will approach venture capital firms. The latter do not need to advertise, because their track record of investments and the knowledge that they have money to invest will attract entrepreneurs like “bees to honey”. Those firms with the best track record and profile in the venture capital industry will tend to attract the best entrepreneurs and business concepts. “Brand image” matters in this business, as in most business enterprises.

For the entrepreneur, he or she should be looking for venture capital firms that offer the following:

- Good reputation with entrepreneurs they have already backed (it is worth doing some reference checks on this) – the expression “success breeds success” is very true in the venture capital industry.

- Knowledge and track record of investment success in similar or adjacent fields to the new enterprise.

- Knowledge and useful industry contacts in the proposed company’s market.

- Personal good chemistry with the general partner at the VC firm, particularly with the lead investor.

- Experience in helping entrepreneurs and a strong reputation as a constructive Board member if the venture capitalist is to join the Board of Directors of the new company—providing constructive input on corporate strategic issues, on an evolving business plan, on recruiting key additional management and on identifying valuable contacts in the venture capital ecosystem (other venture capitalists, investment bankers, lawyers, recruiters and consultants).

Using these criteria, the entrepreneur will be faced with identifying and recruiting the best “lead” investor to whom to present a proposal in the form of a financing term sheet, which will be negotiated to the satisfaction of both entrepreneur and the venture capital firm. This is important because the entrepreneur must be convinced that the particular individual from the lead venture capital firm, and the firms that he or she is associated with, will be a “plus” for the company in all aspects of the company’s growth.

The structure of financing involves a technical discussion that is best left to another paper, but suffice it to say the most common structure involves convertible preferred stock whereby, if the company is sold or undergoes liquidation of assets, the proceeds are first applied to investors who invested in the most senior form of security (usually by investing more capital or taking more risk) before allocation of proceeds is made to junior securities or common stockholders (the latter of which will usually encompass founders, management and employees).

The growth and various stages of financing of a venture capital-backed company can be summarized as follows, with different risk and company valuation criteria applied to each phase of this growth:

The above chart indicates that the very early “seed” funds are often, but not always, supplied by “angel investors” (wealthy individuals who may include family and friends). Funds in subsequent rounds of financing, as the business grows, are provided by venture capital firms, corporate investors, employee pension funds, and eventually by financial institutional investors, university endowments and even sovereign wealth funds. Ultimately, investors seek either cash for their investment or marketable securities through the process of the company going public in an Initial Public Offering (“IPO) or through an acquisition by a company whose own stock is freely traded on the stock market. Such marketable securities in turn can be converted into cash in the stock market.

Concluding Comments

In the United States and other countries where the venture capital industry has taken root, there have been many successes, and it is the rare industry where most participants are not winners: founders, management, employees, investors and government (through the significant revenue from taxes on the gains achieved by the individuals and institutions from their investments).

As the author of this short paper, I can say, having spent a week some eight years ago on a trip to Cuba with my daughter, that the introduction of venture capital into the economy of Cuba would appear to be an incredible boon to the lives of many Cubans and to the Government’s treasury. Why? Because I perceive that, partly due to the challenging economic environment in Cuba, which encourages a shadow economy of entrepreneurship and innovation, in a transparent and regulated market, venture capital would flourish, as it ignites those strands of innovation and creativity for which the Cuban people are well-respected.

[i] The rule of numbers is also referred to as the Rule of 72. The Rule of 72 is a simple way to determine how long an investment will take to double given a fixed annual rate of interest. By dividing 72 by the annual rate of return, investors obtain a rough estimate of how many years it will take for the initial investment to duplicate itself.

Since 1996, Mr. Kibble, has been a founding Managing Partner of Mission Ventures, an early-stage Southern California venture capital firm. With over 40 years of venture capital experience focusing on early-stage information technology companies, Mr. Kibble has, with his partners at Mission Ventures, invested over $500 million in over 60 portfolio companies. Prior to Mission Ventures, Mr. Kibble served as a co-founding general partner of Paragon Ventures in the San Francisco Bay Area, investing over $70 million in over 40 portfolio companies. Previously, Mr. Kibble was a Vice President in the San Francisco office of Citicorp Venture Capital. His early professional experience included working as a research chemist and as a technical sales engineer at Shell Chemicals Limited (U.K.).

Mr. Kibble has MA in Natural Sciences (chemistry) from Oxford University, and an MBA from the Darden School, University of Virginia.

Mr. Kibble has served as director of numerous private and public companies based in California.