The Economic Stakeholders in Cuba: Interactions and Alliances on the Economic Stage

The private sector increasingly plays a significant role in the Cuban economy. Its advances are reflected not only in its growing numbers, but also in the type and scope of its activity.

In Cuba, business activity consists of two fundamental sectors: the state sector, which is the prioritized sector of the economy, and the non-state sector (the “private sector”), which is assigned a complementary role. Nonetheless, it is experiencing a gradual evolution despite its characterization and position as complementary.1

According to Mildrey Granadillo, First Vice-Minister of Economy and Planning, both sectors share a space that is becoming increasingly harmonious.2 A unique part of this change is the ability to interact and generate alliances, although this process also generates disagreements among actors and conflicts with existing regulations.

In the state business sector, there is a process of convergence of state enterprises, their subsidiary entities, and top-level business management organizations that focus on the management of strategic sectors, the provision of public services, and the management and execution of their assigned economic activities. In their commercial activities, state enterprises enjoy autonomy in administration and management. This is evident by their operations in the areas of production or services, labor, finances, credit, investment, and setting prices, among others.

For its part, the private sector consists of businesses and business owners with a variety of forms of organization, ownership and principles of internal organizational. Despite the advances and setbacks in the development of the private sector during the last few years, its diversity and growth have been supported since the adoption of the legal reforms regulating it. The different forms of organization range from cooperatives, including agricultural and non-agricultural cooperatives (CNAs), and micro, small, and medium-size businesses (MIPYMES), which are usually organized in the form of limited liability companies. Some include local private-public development projects in the category of “private sector”, although there is a disagreement about whether they constitute businesses that have economic stakeholders other than the state.

Title II of the Constitution of the Republic of 2019 (the “Constitution”) establishes the economic fundamentals of the Cuban socialist economic system as based on the people’s ownership of the fundamental means of production. This constitutes the main form of property ownership, with the state regulating and controlling it for the benefit of society. Without a doubt, this assigned priority places public ownership in a superior place in relation to other forms of property ownership also recognized in the Constitution, and establishes guidelines for the interaction among them. Article 22 of the Constitution3 defines the forms of property:

- Socialist property of all the people, for which the state acts as a representative and for the benefit of the people as the owner. In this order, the socialist state company is defined as the main actor of the national economy, to which a vital role in the production of goods and provision of services is attributed.

- The property of the cooperatives.

- The property of political, mass, and social organizations.

- Private property.

- Mixed property.

- The property of institutions and associative forms.

- Personal property.

Article 22 itself, in its last paragraph, establishes that “all forms of ownerships of the means of production interact in similar ways. The state regulates and controls the way in which they contribute to the economic and social development.”

The clause defines the basic principle that governs the interaction between the different forms of property ownership and places them in a status of similarity. It also informs the relationship between the different actors that are property owners.

In this way, the different forms of property ownership are positioned – and with them the actors or stakeholders that own and develop them - in similar statuses and not as equals, although they may appear to enjoy equal power over their property. This standing generates an uncertainty subject to multiple interpretations that could put them somewhat out of balance, resulting in irregularities not originally intended by the lawmakers.

The Socialist State Enterprise

As part of the process of updating the Cuban economic model, as well as due to the importance and need to advance in the perfection of the state enterprise system, Decree-Law 34 of 2021 was approved. It regulates the organization and the operation of state enterprises, subsidiary entities, and top-level enterprises management organizations, which it identifies with the generic name of “entities”. They are the business activities of the Cuban state enterprise system.

Among the General Provisions defined in the Constitution, in its Article 9.1, the autonomy of these entities with respect to their administration and management is recognized. In its Article 10, Decree-Law 34 authorizes these entities to form contractual associations for the purposes of creating strategic alliances, production chains, and access to technologies, among others. At the same time, it approves of their association with other state or non-state actors for the purposes of creating new legal entities.

The Self-Employed Worker (Cuentapropista or TCP)

TCP is the status that is granted to a natural person who is authorized to perform one or several economic production or service activities.4 Business activities can be organized as one or more TCPs. As a result, self-employment work is understood to be the activity or activities autonomously performed by natural persons who may or may not own the means and objects of work they use to provide services and engage in the production of goods.

Decree-Law 44 of 20215 updates the general provisions regarding the performance of self-employment work, the procedure for processing authorizations, and the organization and regulatory oversight of TCPs. In its Article 29, the regulation establishes that a TCP can market its products and services to Cuban and foreign natural persons and legal entities. It then authorizes TCPs to engage in the export of goods and services generated within the framework of their activities and the importation of raw materials or goods that are necessary for their products. This must be done through authorized exporter and importer entities.

This appears to place the TCP in the status of any other economic stakeholder. With respect to legal entities, they can be formed both in the state sector and private sector.

Despite the broad authorization of Decree Law 44, TCPs are currently unattractive for a variety of reasons, including:

- The nature and lack of status as an entity offering limited personal liability. A TCP must accept the risks along with the rewards and incur personal liability and potentially loss of his or her individual assets.

- The expansion of the list of economic actors, including the CNAs and the MIPYMES that organize themselves as limited liability companies. In both cases, they enjoy a status of independent legal entities, and the separation between the assets of the individual members and those of the entity, with the resulting limitation on the liability of the owners.

- Sustained resistance by state enterprises and governmental institutions to establishing commercial links with the private sector.

The Non-Agricultural Cooperative

Along with the constitutional recognition of cooperatives as property-owning associations, the development legislation established the distinction between the agricultural cooperatives and CNAs. Both are regulated through their distinctive sets of regulations, each of which define the scope and characteristics of the permitted relationships.6

Article 1 of Decree-Law No.47 of August 19, 2021 establishes the general regime applicable to CNAs (non-agricultural cooperatives) and the rules for their formation, operation, and expiration.7 The regulation defines the CNA as an economic entity that is formed based on the voluntary association of people who contribute money, property and other rights for the satisfaction of the economic, social and cultural needs of its partners as well as the public interest.

The second part of Article 2 establishes the status of the CNA as a legal entity separate from its members, as well as their equity interests, their rights of use and enjoyment regarding their assets, as well as their liability with respect to the obligations contracted with their creditors.

It regulates the participation of CNAs in the contracting of the provision of goods and services with other actors, recognized in the current law, and acknowledges their equal status with those other actors. In contrast, Article 22 of the Constitution states that the various recognized actors have similar status.

Micro, Small, and Medium-size Companies

Decree-Law 46/2021 regarding MIPYMES regulates the creation and operation of this new economic stakeholder. 8

MIPYMES are defined as economic units with separate legal existence and size characteristics that have as their objective the development of the production of goods and the provision of services. They can be organized by the state, the private sector or be owned in partnership by both. They have business autonomy within the framework of the current law. They are generally organized as limited liability companies, thereby separating the ownership of the assets and commercial and other obligations imposed by the legal system from those of the individual members of the MIPYMES.

Their enabling regulation produces an analogous framework as that for the CNAs. In Article 5.4 of Decree-Law 46/2021, MIPYMES, like the CNAs, are given the right to engage in transactions for goods and services with other recognized economic actors and operate with the same status.

Conclusions

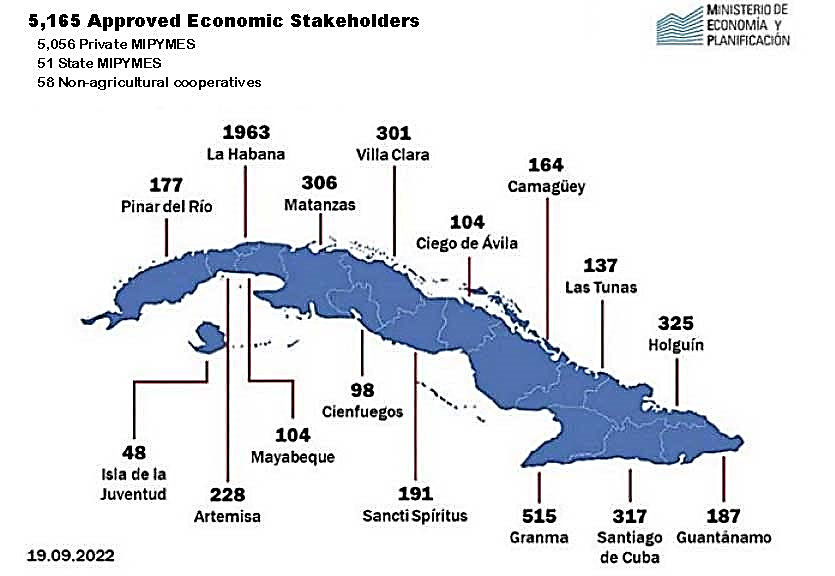

The diversity of the economic actors, their presence in the Cuban economic space and the recognition of their interaction by the Constitution means they are not boxed into watertight compartments. Although a leading role is assigned to the socialist state company as the main form of property owner, that prerogative is not necessarily a detriment to the rest of the economic actors, including the private sector, which is today visible throughout the country and is becoming increasingly important.

The private sector’s advances are demonstrated not only in its growing numbers, but also by the level of activity it is developing, the increase in its contribution to the country’s economy, its use of modeling to adapt to a complex economic environment, its search for alternative solutions, and its interactions with other actors. This could well lead it to transcend its designated role as complementary or secondary in the country’s economic development. However, as of this writing, only a few months after the approval of the laws that enable this new framework, it is too soon to make definitive forecasts.

Both the presence of the private sector and its relationship with the state sector have had to navigate difficulties, limitations, and conditions that impact its normal development, including:

- While the doors were opened to a new scenario many in the existing institutions are resisting the changes and hindering the way towards a range of broader and transparent exchanges and relationships.

- There is a general ignorance of the mechanisms, tools, and legal solutions that legitimate and empower these new actors and their alliances.

- The difficulty in adjusting regulations for foreign commercial relations, banking, financing and specific markets, which had been designed for state economic activity, to the new the private sector.

- Those assigned to apply the regulations and supervise the activity are themselves ignorant of their purpose and appropriate application.

- Negative preconceptions and resistance of the state enterprise sector to establishing relationships and interacting with the various new private economic actors.

1 David Pajón Espina, "The Expansion of the Private Sector in Cuba," Horizonte Cubano, April 2, 2021.

2 Teyuné Díaz y Díaz "Empresas estatales y privadas en Cuba por impulsar la economía," statements to Prensa Latina, November 14, 2022.

3 Each of these forms are defined within the following scope: a) socialist of the entire nation: in which the state acts in representation and for the benefit of it as owner; b) cooperative: the property supported in the collective work of its owner partners and in the effective exercise of the principles of the cooperative movement; c) regarding political, mass, and social organizations: the one that is exercised by these subjects on property intended for the achievement of its purposes; d) private: the one that is exercised on specific means of production by natural persons or Cuban or foreign legal entities; with a complementary role in the economy; e) mixed: the one formed by the combination of two or more forms of property ownership; f) regarding institutions and associative forms: the one that these actors exercise on their property for the achievement of purposes of a non-profit nature; g) personal: the one that is exercised on the property that, without constituting a means of production, contributes to satisfying the material and spiritual needs of its owner.

4 Natalia Delgado and Saira Pons Pérez, "Legal Structures for the Non-State Sector based on the Type and Scale of the Activity," in Horizonte Cubano, July 7, 2019.

5 Published in the Ordinary Official Gazette No. 94 of August 19, 2021.

6 Decree-Law No. 365 on the agricultural cooperatives establishes the general principles regarding their formation, operation, splitting and expiration; Decree No. 354 of December 18, 2018 establishes the Regulation of the aforementioned Decree-Law 365 of 2018. Both published in the Ordinary Official Gazette of the Republic of Cuba No. 37 of May 24, 2019.

7 Published in Ordinary Official Gazette No. 37 of May 24, 2019. Decree No. 354 of the same date, which approves the Regulations of the referenced Decree-Law, is included.

8 Published in Ordinary Official Gazette No. 94 of August 19, 2021.

Dr. C. Maelia Esther Pérez Silveira received a Master in Private Law and Doctorate in Law from the University of Valencia, Spain (2004). Professor of Commercial Law and Private International Law at the University of Holguín, Cuba (2002-2012). Professor of the Center for International Migration Studies of the University of Havana (2012-2015). Professor at the Center for Public Administration Studies (2018- 2022) and, since 2021, Coordinator of the Ibero-American Network on Law, Family, International Migrations and Conflict Resolution, sponsored by the Ibero-American University Association of Postgraduate Studies (AUIP). Author of numerous articles and book chapters on a variety of issues of private international law published in Cuba, Spain and Latin America.