Cuba’s Central Bank Does Not Understand the Demand for Cash

The Cuban Government has decided to force banking use on its population and implement a digital payment system in just six months. It expects this to happen in a country with one of the most backward telecommunication infrastructures and with one of the most underdeveloped banking and payment systems in the region.

Cuba’s Central Bank’s Resolution 111 of 2023 and the explanations given by its newly-appointed president in the television interview program “Mesa Redonda” (Round Table) reveals little understanding about a key concept to any country’s monetary policy, the demand for money. The simple description below identifies the factors that influence money demand by the participants in an economy and illustrates the essential relationships which have to be considered in order to manage monetary policy.

The amount of money required by an economy depends on four key variables:

1. The value of transactions: It is associated with money’s function as a payment method. Money is used to buy and sell available goods and services for a certain price. The demand for money grows if there is a higher volume of transactions (an approximate estimate can be calculated by real GDP growth) or if the price of goods and services increases as a result of inflation.

2. Interest rates: It represents the opportunity cost of keeping money as cash. If the interest rate increases, it becomes an incentive for individuals to deposit their savings in banks and a deterrent to keep cash on hand.

3. Transaction costs, technological advances, and payment systems: The evolution of financial technology and payment systems influence the demand for cash, given that they reduce financial transaction costs and make it easier to convert savings into cash. For example, swipe cards, electronic payments and other digital means tend to reduce the need for physical money.

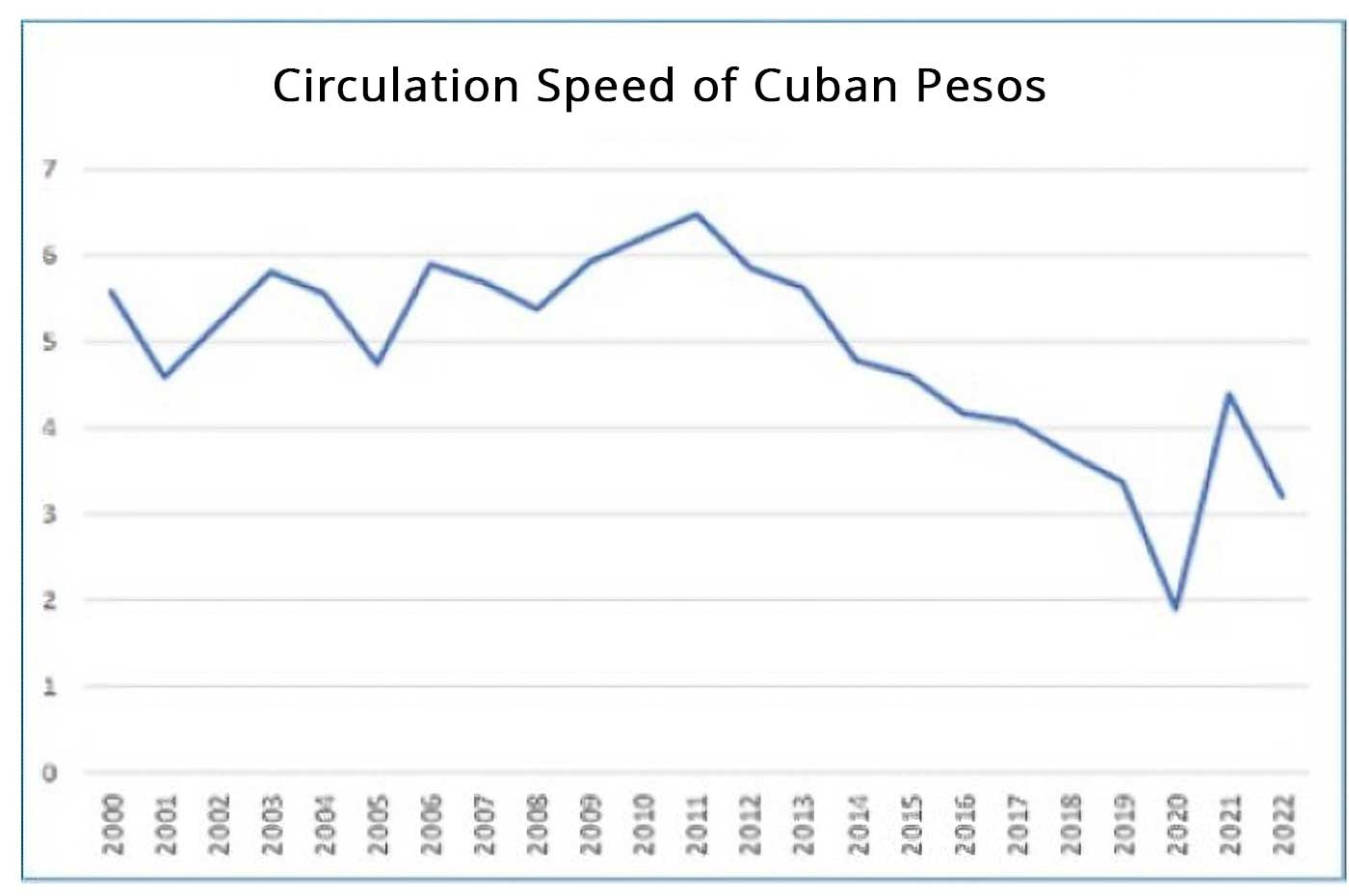

4. The speed at which money circulates: It refers to the speed at which money changes hands over a certain period of time. This variable includes several factors which influence the preference of persons and businesses for liquidity. It is related to their expectations for the future of the economy, informality, uncertainty, etc. It is the most difficult variable to predict, and often changes erratically, making the demand for money unstable.

If we apply these four variables in Cuba’s current context, we can understand why the demand for money has grown so dramatically. Currency in circulation grew 10% every year from 2000 to 2017; but from 2020 to 2022, it grew at an annual rate of 86%.

Rampant inflation and the devaluation of informal exchange rates increased the need for more money to pay for goods and services and to buy foreign currency. Even though real GDP and the number of transactions have decreased, prices have multiplied many times requiring more money.

Nominal interest rates have remain fixed, therefore, in real terms, they are extremely negative. In other words, people are losing money by keeping it in a bank, since their purchasing power decreases every day due to inflation. Banks have not compensated for these losses in savings by increasing their rates to address the current monetary situation in the country.

Transaction costs to withdraw cash at banks or ATMs also increase the demand for cash. Long lines, outdated technology and intermittent telecommunication services represent more reasons to keep money outside banks.

The speed at which money circulates also explains the rising demand for cash. A calculation using nominal GDP shows the speed at which cash circulates dropped by 38% over the last five years compared to the average recorded between 2000 and 2017. The downward trend in the speed of money circulation has been very clear since 2012.

This reflects a structural change in the economic system with the evolution of the private sector, but it may also hint at an increase in informality and uncertainty. All of this has resulted into a greater demand for cash so that the Cuban peso may fulfill its function as a payment method and a reserve of value.

A Recessionary Solution

The answers given in the television interview discussed above omit emphasis of such an essential concept as the demand for money. The financial logic behind Resolution 111 is based on the obsolete model of cash inflows and outflows relevant between state-controlled banks and households. The graph (without numbers) and the analysis provided in the “Mesa Redonda” program to show that there was a net outflow of money from banks was discussed as if assessing monetary policy in the 80s; it was not relevant to the structural changes which have been taking place within the Cuban economy.

With the diversification of labor, trade, markets and production, and a higher participation rate from the private sector, the banks’ model of cash inflow and outflow still does not tell us anything useful if it does not also assess the variables that affect the demand for money. Cash is not required to return to the banks. There is a varying and independent demand for money in households and the private sector that the Central Bank cannot simply ignore.

If the Central Bank wants to influence a reduction in the demand for money, it will have to, first, stop rampant inflation. For that purpose, it needs to stop monetizing the high fiscal deficit, which would require the actual implementation of the macroeconomic stability program recently announced. Another measure in its power to address to reduce the demand for cash is to increase interest rates. An increase in interest rates (at least in proportion to inflation rates) would increase the opportunity cost of keeping cash.

But, no. The preference continues to be the application of administrative measures, regardless of the explanations provided and the innumerable documents written about how those administrative measures will not work.

The Cuban Government has decided to force banking services on its population and implement a digital payment system in just six months. It expects this to happen in a country with one of the most backward telecommunication infrastructures, and with one of the most underdeveloped banking and payment systems in the region, and with an elderly society.

Not only do they seem to ignore that advances in banking services and digital payments would take years, or decades, but also that public trust is an essential element for success. Not too long ago (2021), families witnessed how 80% of the value of their bank accounts vanished as a result of the “monetary reform.”

Nowadays, almost no central bank in the world attempts to set a specific goal for its money supply. This practice was widely used in the past but failed due to unstable demand for money and the difficulty of predicting the “optimum” level of money required by an economy.

Instead, central banks adopted strategies focused on inflation rates, interest rates, and diversifying monetary transmission mechanisms. The demand for money has remained an endogenous variable of financial and economic situations. Central banks provide their economies with all the money they demand. They know the alternative is recessionary.

Money is the oil fueling the economy’s engine. If the amount of oil needed is not supplied, it breaks down. The worst thing is that we do not possess a way to accurately measure the exact amount of money the economy needs, it is constantly changing for a variety of factors.

Forcing the use of banking services by its population and the digital payment system, as proposed by Cuba’s Central Bank, is highly recessionary. They aim to determine how much money the economy needs or should flow back to the banks, overlooking the determinants of money demand and ignoring the context in which the private sector and households are operating.

The explanations given by the Central Bank on how forcing a reduction of cash in circulation will stop inflation and keep the informal economy in check merely display the Central Bank's lack of understanding of monetary policy.

Since the 90s, the Cuban Government has not been able to provide a convertible national currency with a single exchange rate, in line with the country’s economic and financial reality. The economy has had to malfunction with partial dollarization, dual currencies, multiple exchange rates, overvaluation of the official exchange rate, and exchange controls.

To this cocktail of currency distortions, is now added, first, the inability, and, then, the refusal to provide the cash the economy needs.