The Cuban Sugar Industry: Must We Save It?

Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva

Once again, we should consider various ways in which foreign investment could strengthen the Cuban sugar sector, including its partial dollarization. However, the government is moving in the opposite direction.

What joy it must have given many Cubans to hear on national television the debates of the Plenary Session of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party and the National Assembly in December 2021 seeking to save the sugar sector!

In the past, we could not conceive of the national economy, or of Cuba itself, without a sugar industry, as Cuba was once the main world producer, exporting 6 million or more metric tons annually. We frequently recall the phrase of the Cuban landowner José Manuel Casanova: “without sugar there is no country”.

Some of our media criticized the decision years ago to dismantle part of our sugar production infrastructure. In return, some academics were even sanctioned for opposing the misguided policy. The defenders of the policy have since argued that the closure of the sugar mills was the only cause of the national drop in sugar production and the current state of the sugar sector - but this is not the case.

The “Álvaro Reynoso Initiative” (the name given to the restructuring of the sugar industry that began in 2002), did close almost 70 sugar mills over two phases, leaving annual production capacity at only four million tons of sugar. However, the sugar sector had been facing difficulties for a long time for multiple reasons. Among them, are the following:

- Persistently low sugar prices on the international market that did not cover production costs and for years resulted in large net economic losses in Cuban sugar production.

- Decapitalization of the sugar production sector, due to insufficient capital reinvestment and technological obsolescence.

- Unceasing loss of its specialized and professional workforce.

- Lack of incentives for the sugarcane farmer, leading to abandoned fields and lower cane yield per hectare.

- Shortage or untimely arrival of fuel, fertilizers, pesticides and other inputs necessary for production due to lack of financing, among other causes.

- Droughts, plagues, hurricanes and other weather events in some years.

- Accumulation and non-payment of debt by the government, affecting financing.

- Unattractive official exchange rate of the Cuban peso, discouraging exports.

Do all these factors suggest that dismantling the sugar mills was the best solution at the time? Not at all. For example, regarding the first cause mentioned above, the price of sugar in the international market was and is what it is, and most countries did not abandon sugar fields and production in response to the fluctuating international price.

It is true that many producers around the world sell their sugar under agreements with preset prices, which may be lower than those in effect on the international market from time to time. But many other producers use strategies to manage the risk of low sugar prices, such as prioritizing the production of alcohol or other by-products of sugarcane with higher added value. A good case study is the development of the Brazilian sugar industry. While sugar mills were being dismantled in Cuba, Brazil built more of them and with more modern features. Moreover, as a result of continuing capital investments in the sugar industry, those other countries were probably better prepared to face unfavorable price fluctuations because they had modernized and had efficient equipment, both for sugar processing and field production.

On the other hand, Cuba’s sugar industry served as a kind of "donor" of its revenues for the development of Cuba's tourism and biotechnology industries, in addition to helping support government social plans - all at the expense of capital reinvestment for its modernization. Over time, what remained were sugar mills in a deplorable state, the bateyes (buildings with the equipment used in sugar production) and discarded locomotives.

Many years of neglect, along with depressed sugar prices, have brought us to this point. An economic analysis would have concluded that costs of maintaining the failing industry could have been reduced by concentrating production in fewer sugar mills with better supplies of local sugar cane and dismantling only the less efficient ones.

What Were the Options?

Did we really debate and consider other options in depth before we concluded that closures of most of the industry was the only viable alternative? Were there other alternatives? For every problem there is always more than one solution. And this was no exception to the rule.

- Foreign Investment. For example, couldn't the sugar mills, the surrounding countryside and all the related infrastructure have been placed under a foreign investment regime? This would have required an open mind – one without the narrow view that the farmer should not earn more income than others, or that the purchase of production equipment or supplies required approval at the highest government level.

- Use of Freely Tradeable Currency. Likewise, couldn’t we have permitted that portion of the sugar industry targeted for export to operate with moneda libremente convertible (“MLC”, freely convertible currency) instead of forcing it to operate with a devalued peso, disincentivizing export? It is well known that we received very interesting offers from multinational businesses operating in the international sugar industry, familiar with our operations. They proposed alternatives to recuperate the sugar industry, including proposing to make capital investments to construct new sugar mills and modernize some others.

- Cuban Institutional Structures. We should not forget the role of the Cuban institutional structures in disincentivizing production. Some decades ago, we converted the sugar mills into state enterprises required to solicit from government institutions the inputs needed to operate and to do so subject to strict limitations.

- Exchange Rate. Another essential factor is that the official exchange rate, which affects the economic results of the sugar production, serves as an incentive for the sugarcane producer and other industry workers, and determines the valuation of investments. It impacts everything. In short: the exchange rate can stimulate exports, but also discourage them.

In the decade 1991-2000, the price of raw sugar averaged 9.83 US cents (dollar) per pound, with prices in some months in 1999 and 2000 below 7 US cents. In the years 2001-2010 sugar prices reached an average price of 11.57 US cents, but in the first five years of that decade it rarely exceeded 10 US cents per pound. In the 2011-2020 decade, prices improved, averaging 16.71 cents per pound. And in the past year 2021, raw sugar had an average price of 17.86 US cents per pound on the international market. Unfortunately, we had dismantled most of our sugar production facilities by 2002 and could not take advantage of the upswing in prices.

If the price of raw sugar was 10 US cents a pound, this was equivalent to around USD 220.46 for a ton of raw sugar in the international market, excluding premiums and price reductions relating to the quality of the final product. If the average yield achieved in the industry indicated the need to process 10 tons of cane to obtain 1 ton of raw sugar, basically we would obtain a gross income of USD 22.05 per ton of processed cane, or 22.05 peso cubano convertible (“CUP”, Cuban convertible peso) at the then official exchange rate of USD/CUP 1:1.

Sugarcane producers have always earnestly and justifiably pointed out that the low price of sugarcane set by the government for required sale by the farmers to the State known as Acopio served as a disincentive for planting sugarcane as compared with other crops. Therefore, the Agroindustrial Complexes (consisting of the sugar mill and specified lands dedicated to sugar production for those mills) contracted to pay sugarcane producers a price per ton of cane sugar that was much higher than the income to be obtained from its sale, even without taking into consideration other costs and industrial expenses for the production of the raw sugar.

Of course, to adjust for this imbalance it was necessary for the State to allocate funds from its budget, in the form of a subsidies, or to use a USD/CUP exchange rate for the sugar sector that was higher than the official exchange rate. The result was that the difference between the fluctuating international price of sugar and what could be a higher price set by the government then also had to be reflected as a debit to the national budget.

An article in the Granma newspaper on July 9, 2010, entitled "Cut the Root of Sugarcane Indiscipline", reported that until 1997 the sugarcane producer was paid a price of around 14.50 CUP per ton of cane, with the price increasing 3.5 times, until reaching 50.90 CUP per ton. Despite these increases, other crops could be produced and sold at prices exceeding 15,000 CUP per ton. The government imposed price structure for cane cultivation turned sugarcane into the least profitable crop for farmers.

Breaking the Vicious Circle

Also noted in the Granma text was the following quote:

“agricultural yields have shown a decline in recent years, with their most negative expression in the previous harvest, averaging 27 tons per hectare. This unfavorable balance affected 59% of the companies with less than 30 tons per hectare”.

However, around that time, in the report “Sugar in the Andean Community. World Bank SICA Project” (2006) it was possible to compare the yield of tons of cane per hectare of some countries of the hemisphere: 117 in Colombia, 108 in Peru, 72 in Ecuador and 63.8 in Latin America and the Caribbean as a whole.

But that's all history. Has the situation changed after the Monetary Reordering implemented at the beginning of 2021? Can we say that the conditions have been created to ensure that the sugar sector can soon be saved? As we all know, there will be no industry recovery if sugarcane production and yield per hectare cannot be increased.

On November 25, 2020, the Council of Ministers approved the maximum prices to be paid by State entities as of January 1, 2021 to sugar cane producers under Acopio. The sugar cane price was 449.00 CUP per ton.

If the then price of raw sugar remained around 17 cents of USD per pound or about 374.70 USD per ton and the industrial yield was one ton of raw sugar for every 10 tons of cane processed, the country should obtain revenues of 37.47 USD per ton of cane or around 899.00 CUP. After subtracting the other production costs and expenses, the official price of cane would be sufficient for the Agroindustrial Complexes to make a profit and operate without subsidies from the government budget. Or it could produce a margin to cover future drops in the international prices of raw sugar.

Furthermore, if a sugarcane producer obtained a yield of 50 tons of sugarcane per hectare, the producer would be receiving 22,450 CUP per hectare. The cited article in Granma pointed out that by 2010 agricultural producers could receive 15,000 CUP per hectare for other crops. Other media sources cited gross income per hectare of 19,000 CUP for the cultivation of the root crop malanga, or 59,000 CUP for papaya, or 68,000 CUP for one hectare of onions. And those distortions existed before the Monetary Reordering!

The country continues to be caught in the same vicious circle as in previous years: if the price of sugarcane purchased under Acopio is increased by the government, the sugar producers has to be subsidized by the government either by direct subsidies or by the government applying an exchange rate different from the official exchange rate of 24 CUP per USD. On the other hand, if the government were not to increase the price to purchase sugarcane under Acopio, sugar cane producers would be incentivized to harvest other crops - those not intended for export.

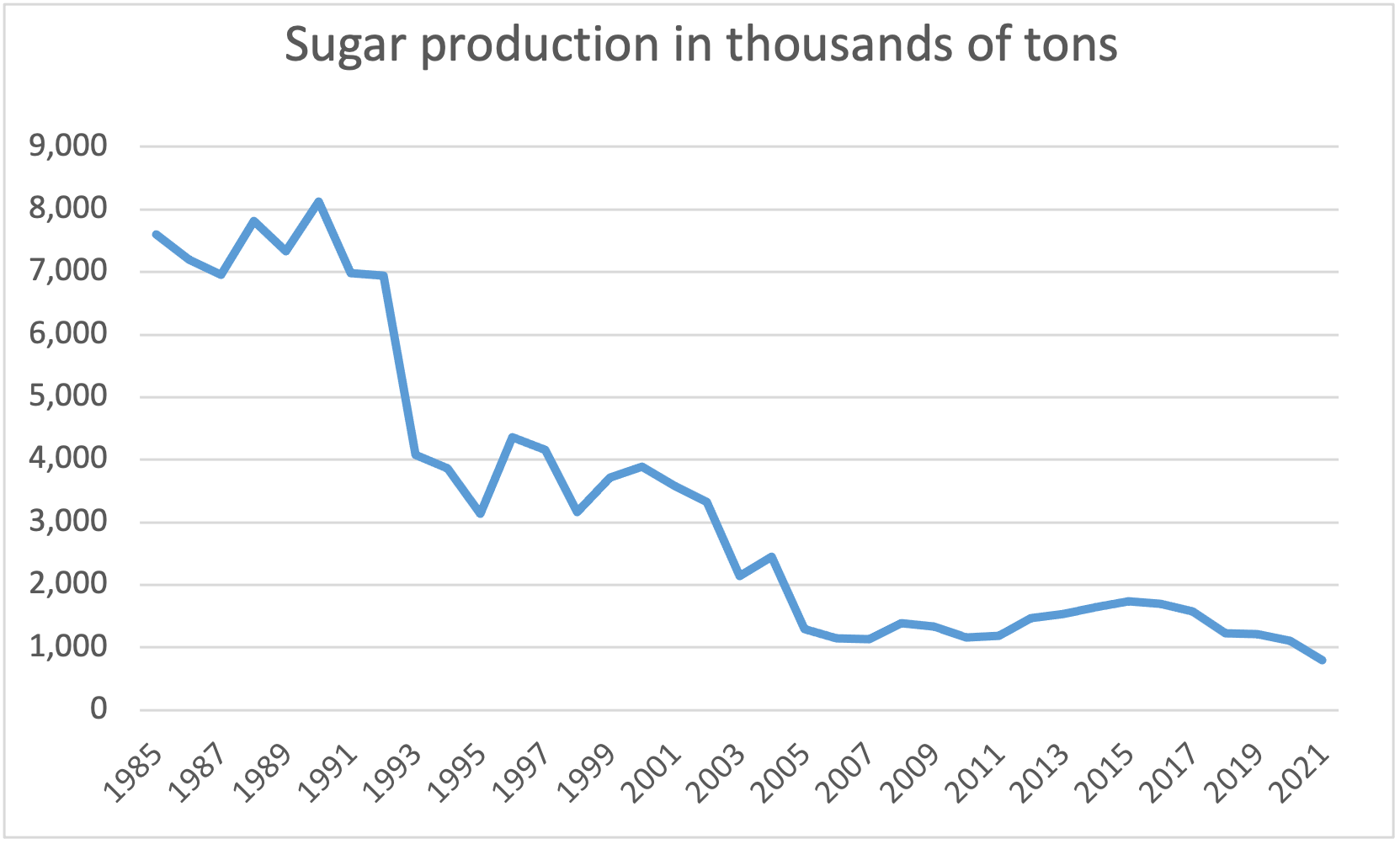

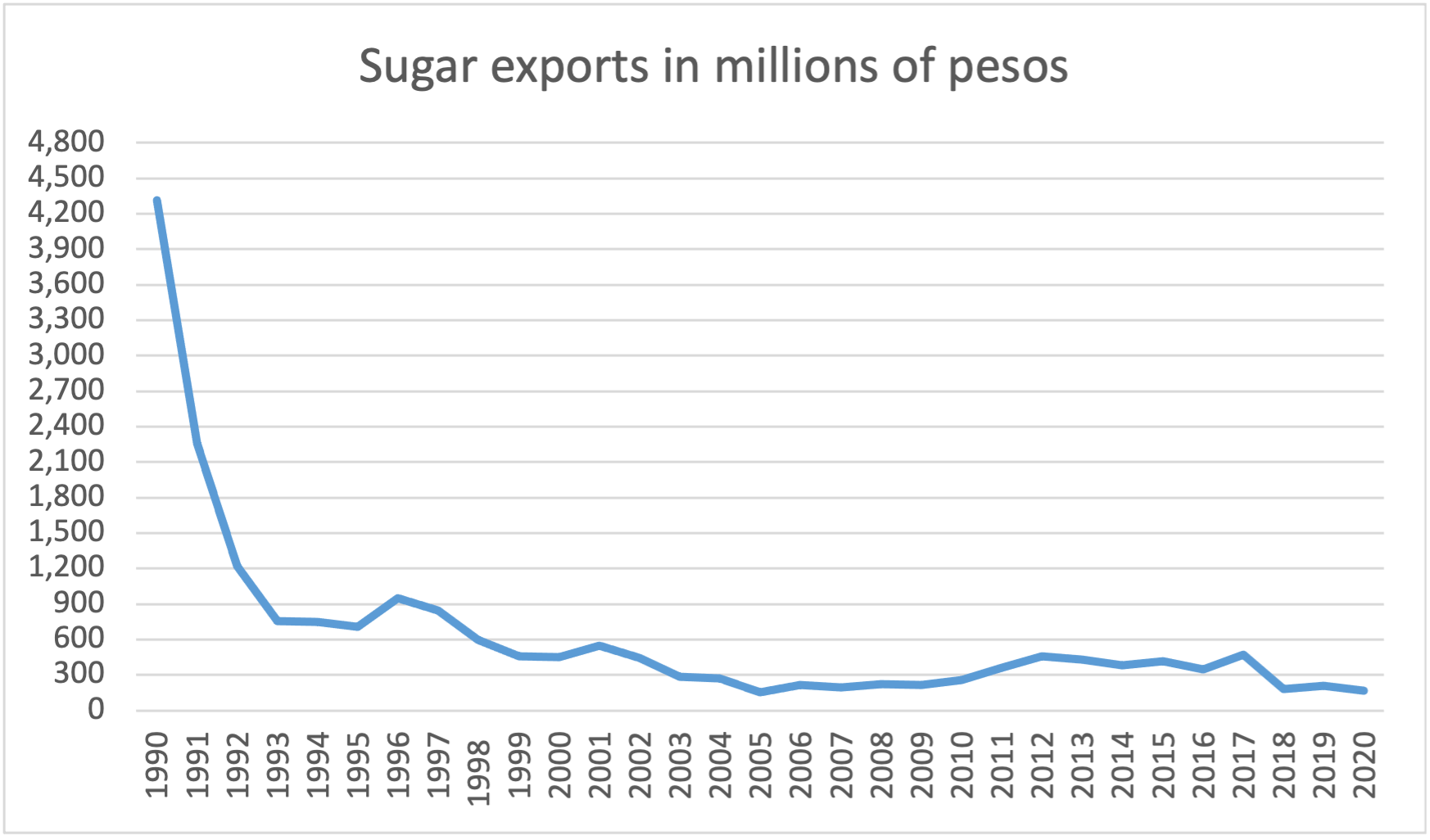

The following graph illustrates the vertiginous fall of what was once the largest industry in the country and its largest source of foreign exchange.

What can be done to break this vicious circle? Perhaps we should begin by getting the input of the managers of the sugar industry?

Let us keep in mind that 449 CUP translate into about 18.70 USD at the official exchange rate at the beginning of 2021, but at the unofficial exchange rate of 70 CUP per 1 USD, it represents a meagre 6.40 USD of gross income for the sugarcane producer (without subtracting production costs) per ton of cane harvested. Meanwhile, we continue to lose valuable specialists in the sugar industry, who also play an important role in increasing raw sugar production.

Once again, we should consider the alternatives of seeking foreign investment in the sugar cane sector or partially dollarizing its operations; however, the current government policy is moving in precisely the opposite direction.

Unless we consider new and innovative proposals and solutions, we cannot achieve the radical changes necessary to save the sugar industry – something for which many of us yearn.

Another question to consider is what it would mean for the sugar sector to operate only in MLC with respect to sugar exports? Or, perhaps we should carry out a partial dollarization of the sector?

First, we should consider that most of the current production is allocated to meet the national demand for sugar, both to satisfy deliveries under the individual ration booklet (the monthly rationing book allocated to each household) and to cover other internal demand. For this internal market, we would set sugarcane acquisition quotas under Acopio for each producer with the payment in CUP, as was approved in the Monetary Reordering, or by designating for use another currency.

These quotas can easily be negotiated depending on the average cane harvest of each producer in recent years. They could become minimum limits to produce for the State under Acopio and any excess amount could be sold for hard currency. Or we could think of this minimum limit as paid in national currency. Any delivery of sugarcane above the fixed state quota would be paid to producers in foreign currency, as this additional sugarcane would be used exclusively to produce sugar for export.

And how much should we pay in hard currency to sugarcane producers? Consider the following examples based on rough calculations:

- If in December 2020 raw sugar on the international market sold at 14.67 US cents per pound, approximately 323.40 USD per ton, equivalent to about 32.34 USD per ton of cane processed, depending of the individual yield of each sugar mill, by using the exchange rate set by the Monetary Reordering that would produce gross income of 776.16 CUP per ton of sugarcane processed – more than double the international price.

- If at the end of 2020 the government set a price of 449 pesos per ton of sugar cane, the producer would be receiving around 57.8% of the price of raw sugar on the international market. The rest (42.2%) would be to cover the other costs and expenses of the industry, marketing, the profits of all the participants in the supply chain, and so forth. (Of course, these sums are achieved by comparison with the price of raw sugar in December 2020. The proportions may differ if we consider international sugar prices in effect in other months).

- If we applied 55% of the production cost to the farming of the main raw material --sugar cane—and allocated 45% to the rest of the costs and concluded that was an adequate allocation, it would only be accurate if we used a fixed price per ton of sugar on the international market. Sugar is a basic commodity, traded on the mercantile exchanges of a variety of markets, so setting a price based on raw sugar futures should not be a problem. For the same reason, it would not be a problem to have fluctuating international prices for the raw sugarcane.

- If raw sugar could be sold at 15 US cents per pound or 330.68 USD per ton, and we used the formula that 55% corresponds to the payment for the raw material necessary for sugar production, and forecasted an industrial yield of 10%, sugarcane producers would be paid 18.19 USD per ton of cane (330.68*55% /10). This amount would then be deposited into the MLC accounts of the sugarcane producers.

Cane cutters with cart full of cane and green field background

That would not represent net income for sugarcane producers. In the same way that we would be set an amount to be paid in national currency for the sugarcane destined for domestic consumption, we could pay for that in fuel, as we would pay for the rest of the productive inputs in national currency. However, for the rest of the sugarcane – that destined for export - the sugarcane producer would be paid in hard currency in their MLC accounts in order to use those funds to purchase necessary inputs available only in hard currency.

Those inputs include fuel, fertilizers, pesticides, agrochemicals, transportation, irrigation equipment, all of which should also be charged in MLC. With this form of payment there should be no delays in delivery and shortages. Producers would continue to have other expenses, for example, for hired labor, water, spare parts for machinery, among others. They could contract for inputs or labor using the appropriate currency, but this would, of course, reduce the net profit of the activity for the State from the producer.

Even if the 18.19 in USD were a net income (which it is not) a sugarcane producer would obtain a yield of 50 tons per hectare. And if the hard currency could be sold at 60 pesos per USD, he would be obtaining 54,570 CUP per hectare – close to what producers obtained from other crops before the Monetary Reordering. This does not result in the sugarcane producers getting rich. But even if that were the case, it would be due to the fruit of their efforts and personal sacrifice. Let us consider what a contribution they would be making to our society - saving the country's sugar sector and achieving a massive increase in sugar exports.

Of course, the proportion of 55% for sugarcane production and 45% to cover the other costs is debatable and reviewable, and the empirical calculations for the examples here are based on prices at the end of 2020. But it all comes down to how the producers of the sugarcane are paid.

The sugar sector can not only be self-sustaining in producing foreign exchange, but it could also become a major net contributor of foreign currency if we manage to increase cane production and sugar exports. The argument that the country does not have the resources to pay so many dollars to sugarcane producers is invalid. The foreign currency would come from the exports of the final sugar product.

The government, however, cannot merely announce that national exports must be increased without taking measures to stimulate the growth of exports. And what is a better place to start than with one of our traditional agricultural products – sugar?

This approach to paying for sugarcane production may be also applied to other export products such as cocoa and tobacco leaves. It implies eliminating the current centralized prices, set by a government ministry or at a higher government level, which with time inevitably become outdated. The current price-setting process requires multiple analyses, negotiations and meetings and always lags behind the international market prices. It is those international market prices that we should use on setting any purchase price for raw materials for export production.

The Future

One of the problems with the Monetary Reordering is that it maintained the old practice of establishing fixed prices by a government bureau, instead of establishing methods for negotiating or revising prices as they fluctuate on the international market. Inevitably, prices set by the government bureau will deviate from the fluctuating market prices and therefore fall out of touch with reality, which experience demonstrates occurs in a very short time.

Once again, some will say that what is being proposed here is the dollarization of the country. Of course, if Cuba had a flexible exchange rate, reflecting the changing economic circumstances, and allowing convertibility from the national currency to foreign currencies, proposals of this type would not be necessary.

But whatever the reasons, the lack of convertibility comes in tandem with shortages. The outdated official exchange rate, with an overpriced national currency, de-stimulates exports. Faced with this reality, we can either leave everything the same or we can adopt alternative solutions to save our battered sugar industry. In the latter case, we will need investment capital to stop further decapitalization. New investments must be made with foreign partners and other actions as outlined above taken so that once again we have sugar to export.