Cuban Bureaucracy and its Impact on the Economy and Society

Tamarys L. Bahamonde

Economist

PhD Candidate, University of Delaware

The high centralization and often low transparency of the Cuban government system generates inefficiencies, slows down decision-making and affects the design and implementation of policies.

The Socialist Bureaucratic State

Bureaucracy is inherent to the state and government administration. However, the Cuban socialist system shares with other socialist systems an identification of socialism with statism – where the state has substantial centralized control over most social and economic affairs. Even those socialist systems that were not initially identified as bureaucratic states, such as China, evolved into strong controlling bureaucracies. The Soviet Union, for example, saw a blossoming of a rigid bureaucracy under Stalin that, according to some authors, eventually led to its reform and the reorganization of its economy for a return of the country to capitalism.

Scholars have called attention to the role of the single-party state in the development of a bureaucratic society. After the socialist revolution, the Communist Party (the “Party”) assumes the role of “vanguard” organization and becomes a parallel bureaucratic institution, whose “judgments are not subjective and value-laden but objective and logically inevitable"[1].

This conception of the intrinsic verity of decision-making by the Party is vital for an understanding of bureaucracy in socialist states. The Party, as the designated leader, with its hierarchal and rigid managerial culture, permeates the government organizations created or restructured in the new society. In former socialist countries, the Party’s intervention, in particular in state-owned enterprises, led to inefficiency, workers’ alienation, and disconnection between the economic plan and the actual conditions of the economy, imposing a vertical managerial style that ignored the input of the various governmental branches and the workers' expectations and criteria in the state enterprises.[2]

The Current Opaque Cuban Bureaucratic Structure

The current Cuban bureaucratic state can be traced back to previous and current experiences in socialist bureaucratic states, which feature highly centralized bureaucracies and a single Party with:

- A pervasive and intrusive role of bureaucratic institutions in all social activity, particularly economic activity[3];

- The state “owning” the means of production on behalf of the people[4]; and

- The Party acting in the role of “night-watcher”[5], second guessing and inserting itself in decision-making by the bureaucracy, thereby discouraging problem solving and decision-making by the bureaucracy and asphyxiating creativity.

Cuba is a socialist state with a single party: The Cuban Communist Party (“PCC”, for the acronym in Spanish for the Party). Article 5 of the Cuban Constitution identifies the PCC as:

“The organized vanguard of the Cuban nation, sustained in its democratic character and permanent linkage to the people, is the superior driving force of the society and the state”[6].

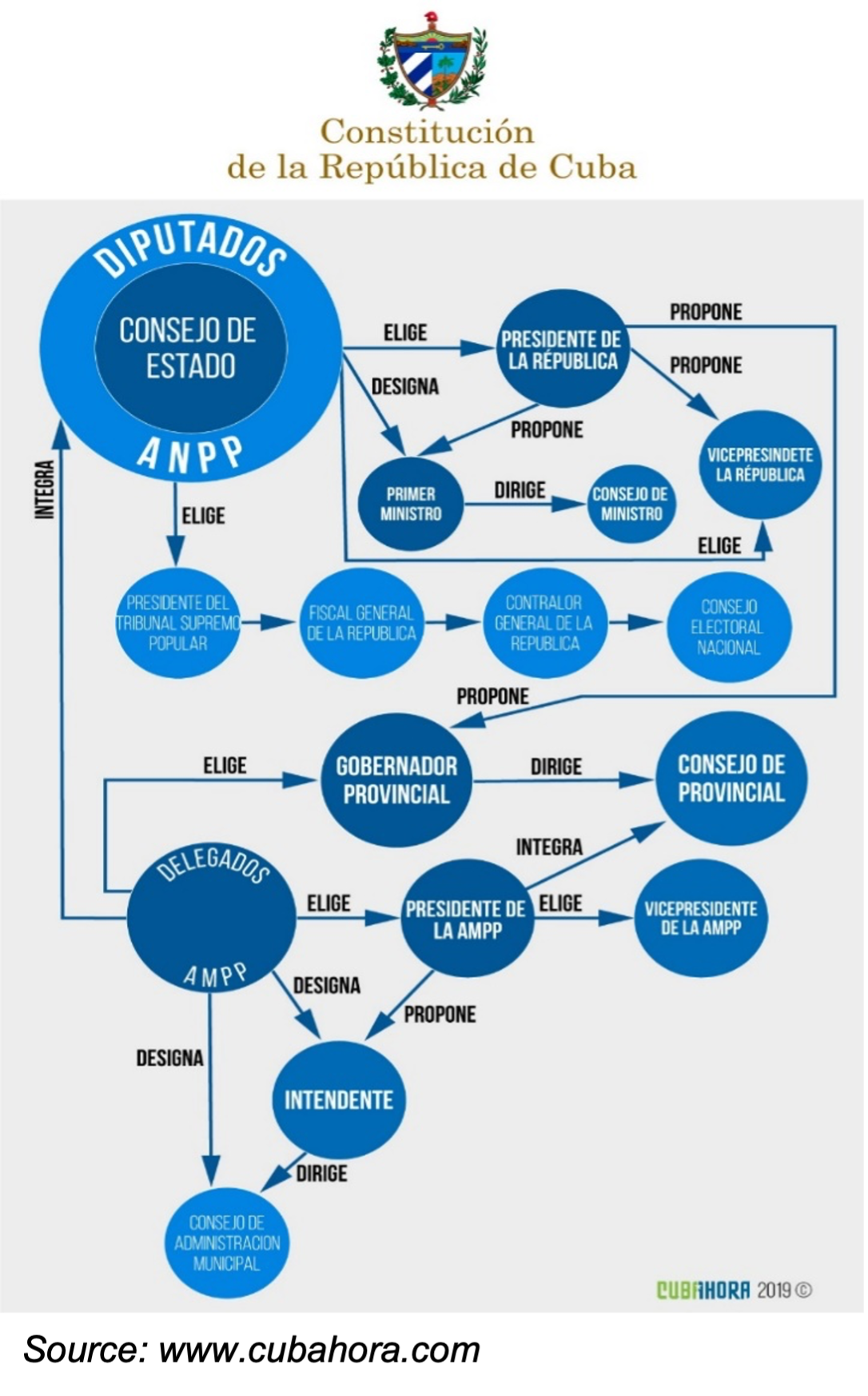

Figure 1 Structure of the Government and State

Note: For further detail on Cuban government structures and current bureacratic leaders, visit https://www.parlamentocubano.gob.cu/index.php/estadocubano/

Ultimately, the PCC is the most crucial political force in Cuba. The scope of the Party’s reach in the political arena has no limit. Despite the official discourse that the National Assembly of the People's Power (“ANPP”, for its acronym in Spanish) is the supreme legislative power within the country, final decisions are placed in the Party's hands. The ANPP cannot ignore or try to ignore the prerogatives given to the Party in the new Constitution.

One example that demonstrates the Party’s power is the guidelines for the re-structuring of the Cuban economic model, approved by a Resolution in the VI Congress of the PCC in 2011. The Resolution not only pre-determined the path to be followed by Cuba in economic policies, but it also decided the roles the other governmental institutions would play, including the ANPP, during the implementation process. Beyond that, the Party bears the responsibility of “controlling, implementing and demanding the compliance with the guidelines approved” by the Party’s Congress[7].

In the past ten years, the Party’s guidelines have been reviewed and adjusted multiple times. In 2021, as part of the continuing restructuring process and in response to the profound economic crisis, the Cuban government put economic policies into effect and introduced some crucial institutional transformations. In May, 2021, the Council of Ministers (designated by the Constitution as an executive power but enabled to issue decrees and resolutions), in a meeting led by the First Secretary of the Party, and President of the Country, Miguel Diaz-Canel Bermudez, introduced and “approved” changes that would restructure the state-owned enterprises, the cooperatives, and the privately owned micro, small and medium enterprises[8]. It was not until August 6, 2021, that the Council of State, which is not headed by President or Prime Minister, and which the Constitution designates as the “superior legislative body,” debated and passed the bills affirming the restructurings that had been presented and previously approved by the Council of Ministers. This is one reason why one can consider the First Secretary of the PCC, Raul Castro - until the VIII Congress in 2021- and currently Miguel Diaz-Canel Bermudez, as the central political figure in the Cuban political landscape. To illustrate the importance of the PCC in the Cuban government, Granma, the official newspaper of the PCC, is the newspaper with the highest circulation in the country.

The Constitution approved in 2018, introduced changes in the political and administrative structure of the government. It addresses two issues: the separation of powers and the rotation of positions in the Government every five years or after re-election for a second five-years term (Title VI, Constitution of Cuba, 2019).

From 1976 to 2019, the date the new Constitution went into effect, the separation of powers was inexistent. Until he retired from public life in 2008, Fidel Castro held the positions of President of the Council of State and the Council of Ministers, First Secretary of the PCC, and President of the Council of Defense. At Fidel Castro’s retirement, Raúl Castro took over until 2018, when a new President was elected: Miguel Mario Diaz-Canel Bermudez. However, Raúl Castro remained as First Secretary of the PCC until 2021, which, under the rights given to the PCC by the Constitution, made him the prominent political leader in Cuba. During the VIII Congress of the PCC, held in April 2021, Miguel Diaz-Canel Bermudez, the current President of the Republic, was elected as the Party's First Secretary of the PCC.

Figure 2 PCC Hierarchal Structure

In addition to the PCC, three organizations operate in the country, alongside the PCC, but subservient to it: the ANPP or parliament, which is a legislative body and meets twice a year, the Council of State, which is a sort of executive committee with the power to legislate between sessions of the ANPP, and the Council of Ministers (which is an executive body with authority to also issue decrees and resolutions). The Council of State is the organization that is designated to lead the country when the parliament (ANPP) is not in session. The President and the Vice president of the ANPP preside over the Council of State, and it has 19 additional members elected by the ANPP. The Prime Minister and six First Vice presidents lead the Council of Ministers. Twenty-four ministers and two heads of institutes constitute the Council of Ministers, comprising all ministries and the main governmental institutions. The ANPP elects the President of the Republic and designates the Prime Minister.

Scholars share concerns about the decision-making process in Cuba. Formally, the ANPP and the Council of State (acting between sessions of the ANPP) are the country’s legislative bodies. However, the hand - or hands - behind Cuban policies appear to be unknown. Parliamentarians do not usually introduce or propose the decrees discussed and approved by the legislative bodies. It is difficult to identify the origin of Cuban policies beyond the abstraction of ministers, the Party or any other governmental body. As in the example discussed above of the re-structuring of the Cuban enterprise, sometimes the legislative body, ANPP, only passes decrees that were introduced and debated by other bodies with different functions specified in the Constitution, such as the Council of Ministers, which is an executive body and therefore should be implementing legislation not proposing it, and the Party. In short, the obscure decision-making style of socialist states such as Cuba impedes decision-making and transparency.

Figure 3 Structure of the Council of Ministers and the Politburo

The Cuban centralized decision-making process comes with social and economic costs and introduces distortions in the system. For instance, the hyper-centralized managerial style produces lags in the response time between when a problem appears and the arrival at a solution. Any economic policy proposal wherever generated within the bureaucracy must go up in the chain of command, wait for the formal institutions and bodies to discuss it, approve it, and send it back down the chain of command for implementation. By that time, the country might well need a different type of policy because the circumstances had changed. Moreover, the fact that the Council of State, a body with only 21 members, holds legislative power to approve and pass bills without having to call the ANPP into session, considerably reduces the popular voice in decision making at the highest level.

Experiences from former and current socialist countries under Party control warn us of the dangers of the hyper-centralized Cuban structure in which the Party holds absolute – or almost absolute – power. The “night-watch” role of the Party discourages decision-making by the bureaucracy and implementation, as the Party could ultimately decide otherwise. Similarly, the leaders of the state enterprises are primarily Party members who owe their allegiance to the Party policies regardless of the operational needs and growth of the enterprises, to the detriment of the economy. It might seem that unlimited and unquestioned power by those who believe in the verity of their decision-making has and could continue to be an obstacle to introducing essential policy changes that promote economic growth.

Sociological and Demographic Characteristics of the Bureaucracy

It is commonly believed that a government composed with individuals of different backgrounds and experiences will represent the interests of those different groups that comprise a society. However, studies have shown that inclusion of individuals from diverse groups from a society does not necessarily lead to effective representation. In many cases, despite their social origins, gender identification, or ethnicity, the loyalty of the representatives lies with their Party, funders or any other political or financial interest. Therefore, they do not represent the interests and priorities of the individual’s social, economic or demographic group.[9]

Despite the changes introduced in the last five years to diversify the bureaucratic structure of Cuba, lack of demographic diversity persists. First, while in 2016 22%[10] of the economically active population had achieved a university education level, all of the top level leaders and government administrators are professionals. This is inconsistent with representing the voice and participation of a blue-collar workers’ majority in the decision-making process.

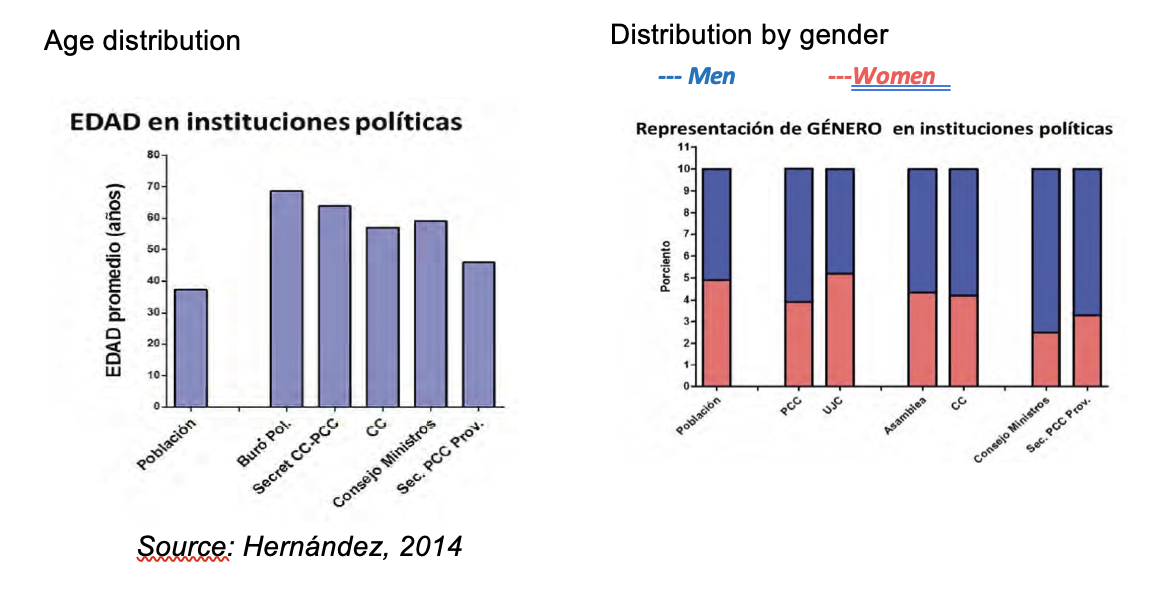

In addition to the discrepancy between the educational level of the top leaders and administrators in the ministries and that of the general population, the top leadership is overly skewed to the oldest members of the population. Half of the members of the Politburo, in 2014, were over 70 years old and there were few women in the Council of Ministers and the leadership of the PCC[11]. After the VIII PCC Congress in 2021, the average age at the top of the PCC dropped to 61 years and only three out of 11 members of the Politburo were women. The PCC also reported that 42.6% of their members are over 55 years old[12].

Figures 4 and 5 Age and Gender Distributions in Political Institutions

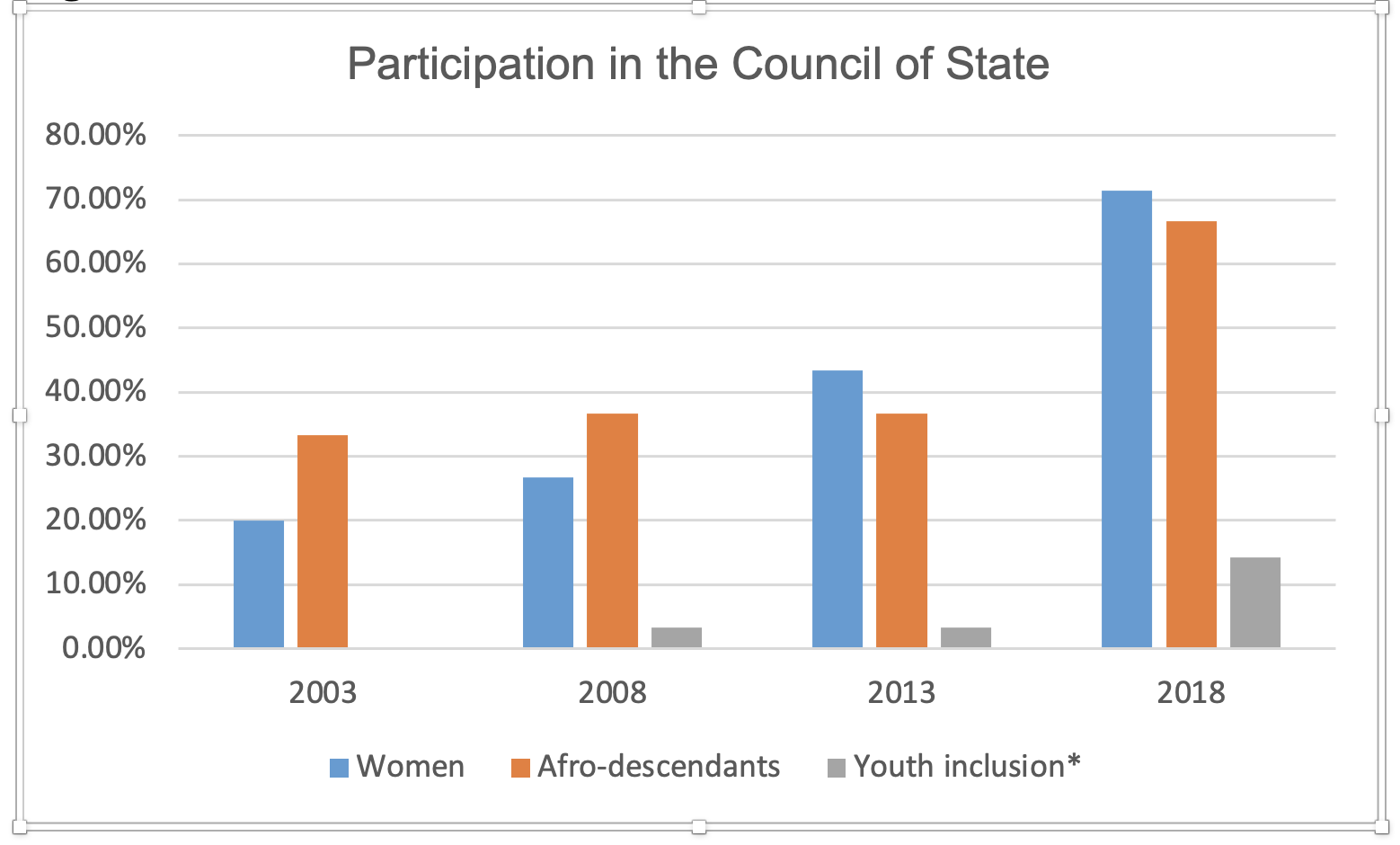

Figure 6 - Participation in the Council of State

Source: Author with data from https://www.parlamentocubano.gob.cu/ and Domínguez, J. I. (2021). The Democratic Claims of Communist Regime Leaders. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 54(1–2), 45–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1525/j.postcomstud.2021.54.1-2.45.

Although Cuba effectively increased the number of women, afro-descendants, and young people in the Council of State in 2018, the difference is not more than three members. The spike in the percentage of women, afro-descendants, and young people in the Council of State in 2018 results from a reduction in the number of members in that year from 30 to 21.

Some lessons can be extracted from this. First, there has been a historic over-representation of older generations in the Cuban bureaucratic structure and leadership. This means that the Cuban youth has lacked a voice within the government structures. While alternative organizations like the Communist Youth and the Federation of University Students (FEU) exist, there is a question of whether they really represent the interests of the Cuban younger generations, and if so, if and how the divergent voices are heard. Second, the delayed and slow changes in the average age at the top of the bureaucratic structure frustrate younger generations who have not had and who do not see a chance to participate in the leadership of the nation.

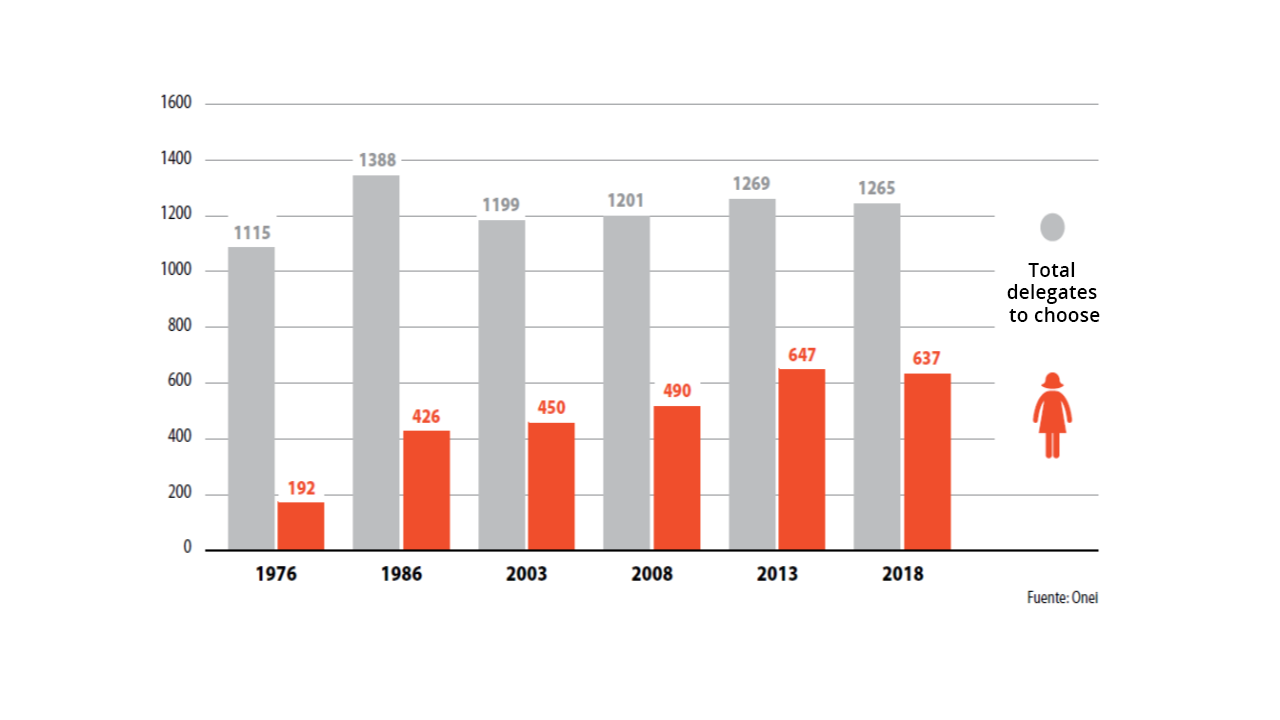

Figure 7 - Female Representation in Local Governments

The implications of limiting the access of women, younger people, and black Cubans to higher levels of government leadership has prevented the government from appreciating and addressing concerns faced by these social groups in their everyday lives, and has, for decades, excluded those issues from the country’s priorities. Issues like gender conflicts, or racial discrimination, or increasing poverty rates among Cuban minorities, for example, have consequently been left out from the government-prioritized agenda. If the Cuban government could appreciate the demands of younger people, maybe they could understand the reasons behind the high rate of emigration, which mainly affects the population under 35 years old, and respond appropriately. Even though inclusion in the decision-making bodies will not guarantee immediate representation, it is a necessary first step for the democratization process and the effective political participation in the government of neglected and vulnerable demographics.

Conclusion

Bureaucracy is inherent to the state and government administration. In general, the Cuban system is highly centralized and obscure, which leads to inefficiencies, slows down the decision-making process, and affects the design and implementation of policies. In addition, bureaucratization in Cuba and the second-guessing role of the PCC has also resulted in a lack of creativity, adherence to routine, blind obedience, and inertia, among other things. Thus, the Cubans coined an appropriate term for referring to the difficulties the country faces due to the bureaucratization and inefficiency of the state: the “domestic blockade”.

[1] Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing Like a State. How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

[2] Boisot, M., & Child, J. (1988). The Iron Law of Fiefs : Bureaucratic Failure and the Problem of Governance in the Chinese Economic Reforms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(4), 507–527.

Dingding Wang. (1990). An Inquiry into the nature of producers behavior in a reforming economy (University of Hawaii). Retrieved from https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/9630/-uhm_phd_9118067_r.pdf

Granick, D. (1987). The industrial environment in China and the CMEA countries. In G. Tidrick & J. Chen (Eds.), China’s Industrial Reform (pp. 103–131). New York: Oxford University Press.

Huchet, J. F., & Richet, X. (2002). Between bureaucracy and market: Chinese industrial groups in search of new forms of corporate governance. Post-Communist Economies, 14(2), 169–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631370220139918

Kornai, J. (1987). The Affinity Between Ownership Forms and Coordination Mechanisms: The Common Experience of Reform in Socialist Countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(3), 131–147.

[3] Dingding Wang. (1990). An Inquiry into the nature of producers behavior in a reforming economy (University of Hawaii). Retrieved from https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/9630/-uhm_phd_9118067_r.pdf

Kornai, J. (1987). The Affinity Between Ownership Forms and Coordination Mechanisms: The Common Experience of Reform in Socialist Countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(3), 131–147.

[4] Dingding Wang. (1990). An Inquiry into the nature of producers behavior in a reforming economy (University of Hawaii). Retrieved from https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/9630/-uhm_phd_9118067_r.pdf

Boisot, M., & Child, J. (1988). The Iron Law of Fiefs : Bureaucratic Failure and the Problem of Governance in the Chinese Economic Reforms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(4), 507–527.

Dingding Wang. (1990). An Inquiry into the nature of producers behavior in a reforming economy (University of Hawaii). Retrieved from https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/9630/-uhm_phd_9118067_r.pdf

Huchet, J. F., & Richet, X. (2002). Between bureaucracy and market: Chinese industrial groups in search of new forms of corporate governance. Post-Communist Economies, 14(2), 169–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631370220139918

[5] Luxemburg, R. (1971). Organizational Questions of Russian Social Democracy. In D. Howard (Ed.), Selected Political Writings of Rosa Luxemburg (pp. 283–306). New York: Monthly Review Press.

[6] For further detail on Cuban government structures and current bureaucratic leaders, visit https://www.parlamentocubano.gob.cu/index.php/estadocubano/

[7] Resolución sobre los Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social del Partido y la Revolución. Retrieved from https://www.pcc.cu/sites/default/files/tesis-resoluciones/2020-07/resolucion_sobre_los_lineamientos_de_la_politica_econ-omica_y_social_del_partido_y_la_revolucion.pdf

[8] http://www.cubadebate.cu/noticias/2021/06/02/aprueba-consejo-de-ministros-perfeccionamiento-de-actores-de-la-economia-cubana/

[9] Htun, M. (2016). Inclusion without Representation in Latin America. Gender Quotas and Ethnic Reservations. New York: Cambridge University Press

[10] Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas de Cuba ONEI. (2019). Anuario Demografico de Cuba 2018.

[11] Hernández, R. (2014). Demografía política e institucionalidad. Apuntes sociológicos sobre las estructuras políticas en Cuba. Espacio Laical, 2 (Special Edition), 32–43.

[12] Castro, R. (2021). Informe Central al 8vo. Congreso del Partido Comunista de Cuba. Retrieved from https://www.pcc.cu/sites/default/files/informe-central/2021-05/Informe Central.pdf

Tamarys L. Bahamonde received her Bachelor degree from the University of Havana in Economics, and an MSc. in Regional Development by the University of Camagüey, Cuba. At the University of Havana, she taught classes related to the Cuban economy and designed and taught undergraduate courses about Cuba's business cycle and labor market. She has published articles in journals and magazines and collaborated on books about economics and Cuban society. She is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Urban Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Delaware. This article summarizes certain ideas she is investigating for her Ph.D. thesis.